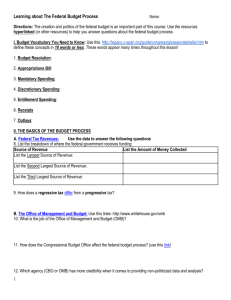

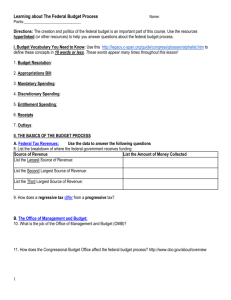

4. The fiscal targets 1 Summary

advertisement