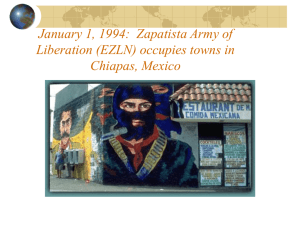

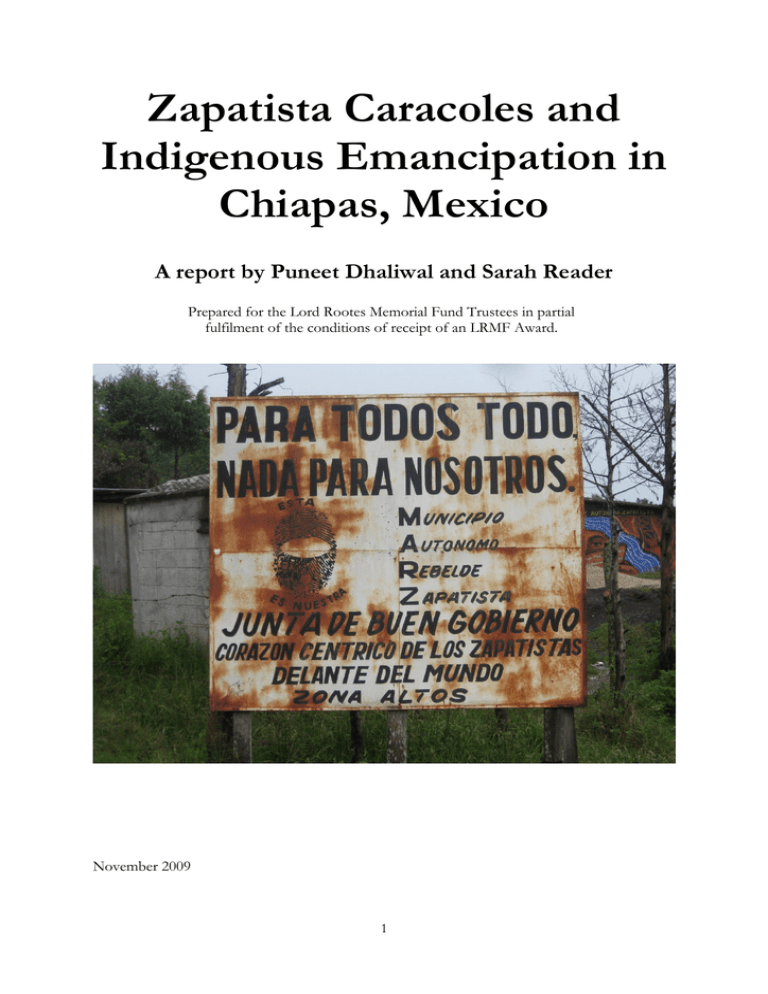

Zapatista Caracoles and Indigenous Emancipation in Chiapas, Mexico

advertisement