W O R K I N G Program Take-Up Among

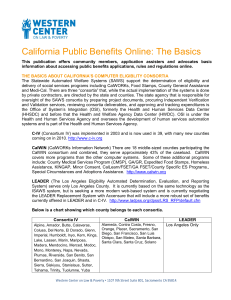

advertisement