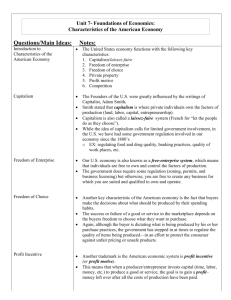

Capitalism at War

advertisement