Document 12787017

advertisement

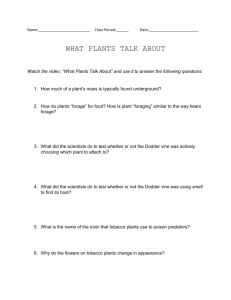

PRUNED DOUGLAS FIR young growth provided the relatively clear veneer shown at left. The distortion of grain is negligible outside of the pruned knots. UNPRUNED DOUGLAS FIR young growth would produce the type of knotty veneer at right. This panel was cut from the inner portion of a pruned fir block. Fact or Fancy? Peelers From Pruned Douglas Fir C AN plywood face stock be recovered from the clear wood grown on young-growth Douglas fir trees pruned at an early age? This question might well be asked by any tree grower who has an eye toward quality improve­ ment of his timber crop. If pruning pro­ duces peelable, knot-free wood, young­ growth logs can be sold as high-quality peelers, substantially increasing their value. To explore this question, forest service researchers pioneered a study during the summer of 1955 to determine the quality and appearance of veneer that might be obtained from pruned logs. Their find­ ings-although not conclusive-indicate that pruning Douglas fir at an early age is a sound investment. Heretofore, possibilities of veneer re­ covery from pruned Douglas fir young growth had been confined largely to theorizing. The main reason for this is that few existing stands were pruned long enough ago to show results. One of the oldest examples of thinned and pruned Douglas fir in the Pacific North­ west is a 56-year-old stand at Kugel By EDWARD J. DIMOCK II Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station-Forest Service U, S. Department of Agriculture * Creek on the Olympic National Forest. This stand supplied the logs for the test peeling. Selected many years ago by the forest service as a testing ground for applied forest research, this stand has had a truly remarkable and dramatic history. In 193 7, when 38 years old, it was thinned and pruned as a wintertime CCC project, and four permanent sample plots were estab­ lished to observe subsequent growth and reaction to thinning. With a second thin­ ning in 1949, the stand showed increas­ ing promise of becoming a good example of intensive forest management. In addi­ tion, the aesthetic appeal of the cleanly pruned boles was felt keenly by all ob­ servers. Unfortunately, however ,the disastrous Port Angeles and Western Railroad fire in 1951 burned heavily over the area and necessitated abandonment of the original experiment. Interestingly enough, the thinned and pruned sample plots sur­ vived the fire with far less damage than the surrounding unthinned timber. Al­ though abandoned for experimental pur­ poses, the stand still conr:tins a number of pruned trees that were merely scorched and not killed in the conrhgration. It ap­ peared that selected trees might well pro­ vide sufficient data to illustrate the possi­ bilities of veneer reco,·er · from pruned logs. Accordingly, in July 1955, two sur­ viving trees with 18 years' growth since pruning were selected for an exploratory recovery analysis. One tree, which grew 6.6 inches at d. b. h. since 193 7, repre­ sented optimum growth on the area; the other, which grew 4.4 inches over the same period appeared to approximate more nearly average growth. The six blocks cut from the two trees ranged in diameter from 14.6 to 16.6 inches inside bark at the small end .wd had grown four to five inches in diameter (inside bark) since pruning. Growth counts av­ eraged seven to ten rings per inch. Through the cooperation of the Geor- EXPERIMENTAL BLOCKS: Side view at left shows 4-foot veneer blocks cut from butt section of Douglas fir that had been pruned to height of about 18 feet. End view of same blocks, above. Dark rings show year in which the trees were pruned. Outer shells of wood represent 18 years of growth since that time. The outer portion produced knot-free veneer. gia - Pacific Corporation in Olympia, Wash,. arrangements were made to peel the blocks and manufacture several dem­ onstration panels. Peeling was done on the company's 4-foot lathe, which is used normally to peel cores from the larger 10-foot lathe. The core lathe, which is equipped with a solid pressure bar, was set to cut core veneer with a thickness of 1/10-inch, a standard size. The lathe chuck was centered in the pith of each block in order to follow the rings as closely as possible and produce the maxi­ mum amount of smooth-cut veneer. As the blocks were peeled, it became increas­ ingly evident that the wood laid down over the knots contained a minimum of cross-graining or distortion and that clear­ faced veneer could be cut almost imme­ diately adjacent to the pruned-knot sur­ faces. When all six blocks had been peeled to approximately 5-inch cores, the recov­ ered green veneer was inspected to de­ termine its quality and general appear­ ance before drying. The best material was relatively clear and contained only scat­ tered defects such as pin knots, splits, torn grain, and occasional partially ob­ scured knots. (The pin knots were pre­ sumably from small internodal branches not removed in pruning.) The remaining veneer, cut nearer the centers of the study blocks, contained a liberal variety of de­ fects, including a great number of both tight and loose knots. Selected Face Panels Following drying, veneer from outer shell areas and knotty core areas was edge­ glued separately to form sheets fully fifty inches square. Then, several sheets of ve­ neer were selected from each group to form the faces of demonstration panels that would show the extreme variations in appearance. Finally, the finished panels of 3-ply If.!-inch construction were sanded to show more clearly the desirable fea­ tures and less obvious defects. Appearance of the dear-faced panels was generally good. With patching the faces could be considered potential grade A under Douglas Fir Plywood Commer­ cial Standards. The knotty veneer, on the other hand, would not grade higher than C. A small amount of torn grain was evident on the faces of all panels, par­ ticularly on those that had been derived from the sapwood portions of the blocks. Improved lathe facilities and peeling practices would be expected to minimize this defect. Due to the pioneer nature of the study, a detailed analysis of the actual peeling operation was not attempted. However, even without an exact determination of production by grades, it was evident that the proportion of high-grade material was not high. Several factors contributed to this. The practice of centering the lathe chuck in the pith, rather than in the geometric center of each block, resulted in some loss due to eccentric bole shape. There also was evidence of a certain de­ gree of carelessness in the original prun­ ing job. Failure to trim the branches cleanly and as close to the bark as possible may have had considerable bearing on the relatively low recovery. Outlook Promising At the present time, this experiment remains as a rough though unique attempt to discover some of the factors that will be met in peeling pruned young-growth Douglas fir. The outlook for future util­ ization of pruned trees in the veneer and plywood industries is indeed promising, and more closely controlled studies of this type are needed. A more comprehen­ siYe study, which will include a quantita­ tive determination of grade recovery, is planned by the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station and the U. S. Forest Products laboratory. It is highly significant that veneer ob­ tained immediately outside pruned knots showed no appreciable distortion in wood structure. It is also noteworthy that a commercially acceptable quality of face stock veneer was obtained from trees with less than 20 years' growth after pruning. The possibilities for producing peeler logs under a normal rotation with several times this growth after pruning make a fascinating topic for speculation. File: Abou t This .on. . ed publicati g the pnnt nin ·-, sca n by d ate cted ,J cre been corre . e This file was av h e ar softw 1fledbY the ent.. . Missca ns id . s may rem am me mistake h0 Wever so } . Reprinted from Leadin g Timber Industry Journal PORTLAND, OREGON Vol. LVII, No.9 July, 1956 PURCHASED BY THE FOREST SERVICE FOR OFFICIAL USE