Factors that Affect Fiscal Externalities in an Economic Union

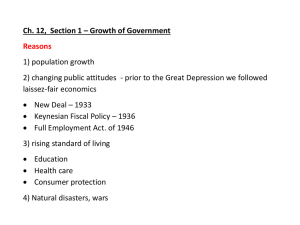

advertisement

Factors that Affect Fiscal Externalities in an Economic Union Timothy J. Goodspeed Hunter College - CUNY Department of Economics 695 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 USA Telephone: 212-772-5434 Telefax: 212-772-5398 E-mail: tgoodspe@shiva.hunter.cuny.edu October, 1999 Abstract: The literature on tax competition suggests that a country's public sector will be influenced by an economic union. For instance, the horizontal tax competition literature suggests that the expectation that a mobile factor will leave a jurisdiction in the face of a non-benefit tax will result in downward pressure on mobile tax bases within a jurisdiction, and hence lower than desired levels of nonbenefit taxes and spending. Despite these important insights, little work has been done to assess the factors that affect fiscal externalities and the resulting impact of these externalities on public spending, taxation, and migration. This paper uses a simulation model to gauge the impact of the fiscal externalities in an economic union under alternative assumptions concerning expectations of tax base responsiveness, the time frame, the relative progressivity of member country tax systems, and the variance of incomes in the union. JEL Classification: H23, H73 Keywords: Fiscal federalism, Fiscal externalities, Tax competition This paper is a revised version of “The Effect of the Characteristics of New Members of an Economic Union on Redistributional Policies” initially presented at the International Seminar in Public Economics, May 27-29, 1995, University of Essex. The revision was inspired by the research and discussions presented at the ZEW conference on “Fiscal Competition and Federalism in Europe” June 1-3, 1999. My thanks to participants in both seminars and Howard Chernick for helpful discussions. I. Introduction The economies of the nations of the world are becoming increasingly integrated. This integration has been in part a natural consequence of increased trade and the mobility of financial capital between countries, but has been hastened by the emergence of economic unions such as the European Union (EU) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The literature on tax competition suggests that a country's public sector will be influenced by an economic union. For instance, the horizontal tax competition literature, such as Wildasin (1988, 1989) and Zodrow and Mieszkowski (1986), develops a concept of a fiscal externality. The basic insight is that the expectation that a mobile factor will leave a jurisdiction in the face of a non-benefit tax will result in downward pressure on mobile tax bases within a jurisdiction, and hence lower than desired levels of non-benefit taxes and spending. A similar point is made in Goodspeed (1989). Migration incentives are created if non-benefit taxes are levied on mobile resources because the mobile factor’s tax-price is lower in a jurisdiction with a higher mean tax base. If migration results in the factor contributing less to revenue than it consumes in public services, its’ migration imposes an externality on other factors resident in the jurisdiction. These insights have important consequences for redistributional policies. Redistribution by definition entails taxes that do not reflect benefits. If the factors that are so taxed become mobile because of an economic union, redistributive taxes will result in an inefficient spatial allocation of resources and will tend to be competed down. Despite these important insights, little work has been done to assess the factors that affect fiscal externalities and the resulting impact of these externalities on public spending, taxation, and 2 migration. What factors influence the impact of fiscal externalities? This paper uses a simulation model to gauge the impact of the fiscal externalities in an economic union under alternative assumptions concerning expectations of tax base responsiveness, the time frame, the relative progressivity of member country tax systems, and the variance of incomes in the union. In a base case in which two jurisdictions use proportional income tax systems, the time frame (reflected by the elasticity of supply of housing) is found to have a large impact on migration, but much smaller effects on tax rates and public spending. In contrast, the expected responsiveness of the tax base has a large impact on public spending and tax rates, but little impact on migration. When the tax systems of the two jurisdictions differ in their progressivity, the expected responsiveness of the tax base has a profound impact on migration patterns. Finally, the variance of the income distribution is found to have a strong impact on tax rates and public spending, and relatively small effects on migration patterns. The results have some interesting implications for fiscal competition in Europe. First, they emphasize that fiscal externalities affect not only movements of factors, but also internal public spending and taxation decisions. Empirical work should examine the impact of fiscal externalities on public good levels, not just on the movement of factors from one jurisdiction to another. Second, the results concerning the variance of the income distribution suggest that the addition of new members with incomes substantially different from current members can have a strong impact on current members’ taxation and spending decisions. The paper is organized in the following manner. The next section discusses fiscal externalities in a simplified version of the model to be simulated. Section 3 briefly discusses the simulation model used. Section 4 presents the results of three sets of nine simulations each that 3 attempt to gauge the impact of the fiscal externalities in an economic union under alternative assumptions. Section 5 concludes. II. The Fiscal Externality The fiscal externalities discussed in this paper combine the work of Goodspeed (1989) with that of Wildasin (1988, 1989) and Zodrow and Mieszkowski (1986). Before considering a simulation model based on Goodspeed (1989) and results designed to measure changes in the fiscal externality, it is useful to discuss the fiscal externality in a simpler framework. To do this, we consider the simulation model that follows, but ignore the housing market. The elasticity of the supply of housing is used in the simulations to allow for real income differences that could arise in the short or intermediate run in an economic union. The housing market is unnecessary to discuss fiscal externalities, however. Consider a simple world of two jurisdictions and the optimization problem of one of the governments, calling this jurisdiction 1. We assume that the preferences of the median voter are defined over a private good, X, and the per-capita level of a publicly provided private good, G1: (1) Jurisdiction 1 is assumed to finance expenditures using a linear income tax; hence, local government one’s budget constraint is given by (2) 4 where ym1 is the mean income of jurisdiction one. The tax base of each jurisdiction will be influenced by its own fiscal decisions and those of the other jurisdiction; hence, ym1 = ym1 (a1, a2, t1, t2). We assume that this is due solely to the mobility of the tax base; that is, we assume that an individual’s (before tax) income is exogenous and hence does not depend on tax rates. We will interpret this function as jurisdiction 1's expectation of its tax base given its choice of tax parameters and those of the other jurisdiction. Voting models that attempt to explain the progressivity of a tax system quickly run into difficulties. Even a simple linear income tax is problematic because there are three voting parameters, the level of the public good and the two tax parameters, only one of which is determined by the government budget constraint. Kramer (1973) shows that if all combinations of the remaining two dimensions are admitted as possible candidates, majority rule will fail to generate an equilibrium. Denzau and Mackay (1981) and Inman (1985) provide excellent discussions of some of the proposed solutions to this problem. One approach is what Shepsle calls "structure induced equilibrium." Shepsle (1979) uses a serial election process (with myopic expectations) in which the essential institutional constraint is that each dimension is voted on one at a time. Denzau and Mackay (1981) extend this analysis to consider the case of perfect foresight expectations, and show that the equilibrium generated will generally be different than that under myopic expectations. A different solution is that of Roberts (1977), who holds one of the parameters, G, fixed and hence reduces the problem to one of voting over a single dimension. Migration models that consider voting and redistribution have proceeded by simplifying the 5 problem in different ways.1 We will assume a linear income tax, and consider a variant of the Roberts solution in which we hold the intercept term fixed. A set of simulations that follow will change the exogenous intercept parameter for one of the jurisdictions to gauge the impact of differing degrees of progressivity. The problem of jurisdiction 1 is to choose the tax rate to maximize the median voter’s utility subject to the median voter’s budget constraint and his expectation of jurisdiction 1's budget constraint: (3) where ym1 (a1, a2, t1, t2) is the function noted above. Substituting the constraints into the objective function and differentiating yields the first order condition (4) 1 Goodspeed (1989) considers a proportional income tax and hence eliminates the constant term of the linear income tax. Epple and Romer (1991) use the approach of Roberts (1977) and essentially set G equal to zero; a proportional property tax is used to generate a lumpsum subsidy that is added to each person's income. The analysis in Goodspeed (1995) assumes that the intercept is greater than or equal to zero, interprets the intercept as a head tax, and investigates the choice between financing by a proportional income tax or a head tax. His approach can be thought of as a hybrid of the serial voting and Romer approaches. Goodspeed's voters consider the optimal choice of each parameter holding the other parameters fixed; it turns out that each voter will choose one of the two tax parameters to be zero. In a sense, this reduces the public choice problem to a single dimension as in Roberts, but unlike the Roberts case, no parameter is exogenously fixed. Each voter endogenously fixes one of the tax parameters to be zero. 6 Rewrite the first order condition as (5) The right hand side is the perceived tax-price of public spending. The work of Goodspeed (1989) takes Mym1 / MtL1 to be zero. Nevertheless, a fiscal externality is present and location decisions are distorted in Goodspeed’s model as long as the mean income of jurisdiction one differs from that of jurisdiction two. The distortion in location incentives results because an individual’s tax-price is lower in a jurisdiction with a higher mean tax base. This is illustrated by the two solid budget constraints plotted in Figure 1. For a given level of public service, an individual will always prefer the wealthier jurisdiction since the tax price is lower. (Indifference curves are plotted as concave functions with utility rising as one moves toward the southeast of Figure 1). An incentive is created for a migrant to move to a wealthier jurisdiction where he will contribute less to revenue than he consumes in public services. He will thus impose an externality on everyone else, as explained in Oates (1972) and Goodspeed (1989, 1995). The term Mym1 /MtL1 is the focus of the fiscal externality discussed in the horizontal tax competition literature such as in Wildasin (1988, 1989) and Zodrow and Mieszkowski (1986). That literature argues that tax base mobility imposes a fear that non-benefit taxes will drive out the mobile tax base, and leads to lower tax rates. The effect of this externality is similar to that explored in Goodspeed (1989): if Mym1 / Mt1 is negative, the price of local public services is higher than it would be if the decisive voter ignored the mobility of the tax base. This is illustrated by the dotted budget 7 constraints in Figure 1. While this will clearly have an impact on the internal choice of spending levels and tax rates in both jurisdictions, the impact on migration of the taxed factor is less clear since this depends on relative prices between jurisdictions one and two. The impact of this fiscal externality on migration and the public sector may therefore be quite different than that explored in Goodspeed (1989). The simulations that follow are designed to gauge the impact of these fiscal externalities on public spending, tax rates, and migration under different scenarios. This is achieved by considering three sets of nine simulations. In each set, the simulations consider 3 values for Mym/Mt and 3 values for the elasticity of the housing supply. (The housing supply elasticity is interpreted in terms of the time frame under consideration.) The first set of simulations assumes that both jurisdictions use proportional income taxes. The second set of simulations considers a proportional tax system for one jurisdiction and a progressive tax system for the other. The third set of simulations again assumes that both jurisdictions use proportional income taxes as in the first set of simulations, but considers a larger variance of the income distribution. III. The simulation model The simulation model is based on the model developed in Goodspeed (1989) that is in turn based on the models of Westhoff (1977) and Epple, Filimon, and Romer (1984). These models embed a median voter model in a migration model and both the voting equilibrium and the migration equilibrium are determined endogenously. Two important assumptions of the model that are used to establish both equilibria is that income is a continuous variable and indifference curves are single8 crossing in income. As the equilibrium properties of these models are well known, and this is not the focus of the current paper, I will not dwell on proving existence in the model. Two differences from previous versions of the model are worth noting. First, a linear income tax is used, but the intercept term is taken as exogenous. Second, a jurisdiction has some expectation of its tax base function, and hence some expectation of how the tax base will change as it changes its tax rate. A value for Mym/Mt is exogenously specified in the simulations. Other than these differences, the model is similar to that developed in Goodspeed (1989). The model will be simulated for two jurisdictions. The voting equilibrium of the model is determined by the equality of the slope of the median voter's indifference curve and the government budget constraint within each of the two jurisdictions. The migration equilibrium is determined by a single equation that generates indifference for a particular income level between the pair of jurisdictions. This partition of the income distribution allocates the population to jurisdictions such that everyone is satisfied with the jurisdiction in which he resides. This also defines the jurisdiction population and tax base. Within each jurisdiction, the supply and demand for housing determines the equilibrium price of housing in that jurisdiction. The model thus consists of 7 equations to be solved for the 7 endogenous variables: the tax rates and level of public spending in each jurisdiction, the price of housing in each jurisdiction, and the income level of the indifferent individuals. The simulations will assume that utility is of the Stone-Geary form. The continuous distribution of incomes will be assumed to be uniform; hence mean and median incomes are identical. The housing supply function is of the form assumed in Epple, Filimon, and Romer (1984) and Goodspeed (1989). 9 IV. Results Before presenting results of the simulations, a word on the interpretation of the model is useful. In the very long run, migration suggests that real incomes will be equalized. However, this is not likely to happen across country borders, even with free migration, for a very long time. The model here allows for real income differences through the housing market. Over time, such differences may become less important. This will be reflected in the simulations by increasing the elasticity of the supply of housing. As mentioned, we consider three sets of nine simulations. The first set of simulations assumes that both jurisdictions use proportional income taxes (a1 = a2 = 0). The results for the equilibrium population, tax rate, and public spending in each jurisdiction are presented in Table 1 for the nine simulations. Each simulation row corresponds to a different value for Mym/Mt and each simulation column corresponds to a different value for the housing supply elasticity. The striking feature of the simulations is the differing impact on migration and public sector spending of the externalities explored in Wildasin (1988, 1989) and Goodspeed (1989). The first row assumes no expectation of a decline in tax base, yet the migration impact in the very long run is extremely large. The impact on public spending is modest in the first row simulations. In contrast, the first column simulations show that a larger expectation of a decline in the tax base has a very large impact on public spending and tax rates, even in the very short run. The impact on migration is minimal in the first column simulations. The second set of simulations considers a proportional tax system for one jurisdiction and a progressive tax system for the other. Prior to presenting these results, a word on the definition of 10 progressivity is in order. Many measures of progressivity may be considered, but we consider the derivative of the average tax rate with respect to income. If the derivative of the average tax rate is positive, the tax system is said to be progressive. Since the tax paid by an individual with income y is T = -a + ty, the average tax rate is -a/y + t and the derivative of the average tax rate with respect to y is a/y2, which is positive as long as a is positive, so the tax is progressive. Further, a change in a parameter of the tax system increases the progressivity of the tax system if the derivative of the progressivity measure with respect to the parameter (i.e. the cross partial of the average tax rate) is positive. Since the cross-partial of the average tax rate with respect to income and t is zero and with respect to income and a is positive, an increase in the parameter a will increase the progressivity of the tax system and an increase in t will not affect its progressivity. This characteristic of the linear income tax will be exploited in the next set of simulations; the more progressive tax system will have a higher value for the intercept term. Table 2 presents the results of the second set of simulations that assume a proportional tax system for jurisdiction one (a1 = 0) and a progressive tax system for jurisdiction 2 (a2 = .2). Again, the results for the equilibrium population, tax rate, and public spending in each jurisdiction are presented for the nine simulations. The first row of simulations shows a somewhat more accentuated migration from the poor to the wealthy jurisdiction. The most striking feature of these simulations compared to those of Table 1 comes from the next two rows, however. In these last two rows, the progressivity of the tax system of jurisdiction 2 combined with the expected reduction in tax base reverses the migration pattern. Instead of a migration from the poor to the wealthy jurisdiction, we find a pattern of migration toward the poorer jurisdiction. The problem for jurisdiction 2 is that it must impose a higher tax rate to achieve the same level of public spending as in Table 1. Public 11 spending becomes so much more expensive that the high tax base incentive for locating in the wealthy jurisdiction is overwhelmed. The expected tax base mobility parameter is much more important for migration patterns when two jurisdictions have diversely progressive tax systems. The third set of simulations again assumes that both jurisdictions use proportional income taxes as in the first set of simulations, but considers a larger variance of the income distribution. The larger variance is modeled by increasing the support from [2, 3] to [2, 3.5]. For comparison to the other simulations, the height of the uniform distribution is reduced to .67 to maintain the same aggregate income and population. The results are presented in Table 3. While somewhat more migration towards the wealthier jurisdiction than in Table 1 is seen, the most striking difference from the results in Table 1 is substantially lower tax rates and public spending. A wider distribution of income in itself induces a reduction in tax rates and public spending. V. Conclusion The economies of the world are becoming increasingly integrated, in part because of the emergence of economic unions. The literature on horizontal tax competition suggests that an economic union can have an impact on the public sector of member countries. Despite important insights provided in the tax competition literature, little work has been done to assess the factors that affect fiscal externalities and the resulting impact of these externalities on public spending, taxation, and migration. This paper uses a simulation model to gauge the impact of the fiscal externalities in an economic union under alternative assumptions concerning expectations of tax base responsiveness, the time frame, the relative progressivity of member country 12 tax systems, and the variance of incomes in the union. In a base case in which two jurisdictions use proportional income tax systems, the time frame is found to have a large impact on migration, but much smaller effects on tax rates and public spending. In contrast, the expected responsiveness of the tax base has a large impact on public spending and tax rates, but little impact on migration. When the tax systems of the two members of an economic union differ in their progressivity, the expected responsiveness of the tax base has a profound impact on migration patterns. Finally, the variance of the income distribution is found to have a strong impact on tax rates and public spending, and relatively small effects on migration patterns. The results have some interesting implications for fiscal competition in Europe. First, they emphasize that fiscal externalities affect not only movements of factors, but also internal public spending and taxation decisions. Second, the results concerning the variance of the income distribution suggest that the addition of new members with incomes substantially different from current members can have a strong impact on current members’ taxation and spending decisions. Empirical work is needed on the impact of fiscal externalities. Such work should examine the impact of fiscal externalities on public good levels and tax structure, not just on the movement of factors from one jurisdiction to another. 13 Bibliography Denzau, Arthur T. and R. J. Mackay. 1981. "Structure-Induced Equilibria and Perfect-Foresight Expectations." American Journal of Political Science. 25: 762-779. Epple, D. and T. Romer. 1991. "Mobility and Redistribution." Journal of Political Economy. 99: 828-858. Epple, D., R. Filimon, and T. Romer. 1984. "Equilibrium Among Jurisdictions: Toward an Integrated Treatment of Voting and Residentail Choice." Journal of Public Economics. 24:281-308. Goodspeed, Timothy J. 1989. "A Re-examination of the Use of Ability to Pay Taxes by Local Governments." Journal of Public Economics. 38:319-342. Goodspeed, Timothy J. 1995. "Local Income Taxation: An Externality, Pigouvian Solution, and Public Policies." Regional Science and Urban Economics. 25: 279-296. Inman, Robert P. 1987. "Markets, Governments, and the 'New' Political Economy," in A.J. Auerbach and M. Feldstein, eds., Handbook of Public Economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Kramer, Gerald. 1973. "On a Class of Equilibrium Conditions for Majority Rule." Econometrica. 41: 285-297. Roberts, K.W.S. 1977. "Voting over Income Tax Schedules." Journal of Public Economics. 8: 329340. Shepsle, Kenneth. 1979. "Institutional Arrangements and Equilibrium in Multidimensional Voting Models." American Journal of Political Science. 23: 27-59. Westhoff, F. 1977. "Existence of Equilibria in Economies with a Local Public Good." Journal of Economic Theory. 14:84-112. Wildasin, D., 1988. “Nash Equilibria in Models of Fiscal Competition.” Journal of Public Economics. 35: 229-40. Wildasin, D., 1989. “Interjurisdictional Capital Mobility: Fiscal Externality and a Corrective Subsidy.” Journal of Urban Economics. 25: 193-212. Zodrow, G., Miezskowski, P., 1986. “Pigou, Tiebout, Property Taxation, and the Underprovision of Local Public Goods.” Journal of Urban Economics. 19: 296-315. 14 Figure 1 15 Table 1 Migration and Public Sector Impact of Fiscal Externalities: Similarly Progressive Tax Systems (a1 =a2 = 0 for all simulations) Housing supply elasticity tax base responsiveness Mym ----- = 0 Mt My region elasticity=1 elasticity=3 elasticity=9 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 tax rate .21 .22 .28 .28 .30 .30 public good expenditure .48 .62 .68 .76 .62 .76 percent of population 49 51 39 61 14 86 tax rate .12 .12 .14 .13 .14 .14 public good expenditure .28 .34 .30 .36 .29 .35 percent of population 48 52 35 65 10 90 tax rate .09 .09 .09 .09 .10 .09 public good expenditure .20 .24 .20 .25 .19 .24 percent of population 48 52 31 69 5 95 variable m ----- = -5 Mt Mym ----- = -9 Mt 16 Table 2 Migration and Public Sector Impact of Fiscal Externalities: Diversely Progressive Tax Systems (a1 = 0; a2 = .2 for all simulations) Housing supply elasticity tax base responsiveness My region elasticity=1 elasticity=3 elasticity=9 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 tax rate .22 .29 .29 .36 .30 .38 public good expenditure .49 .61 .62 .76 .62 .75 percent of population 49 51 36 64 9 91 tax rate .12 .16 .14 .16 .14 .16 public good expenditure .27 .24 .32 .26 .33 .28 percent of population 55 45 64 36 80 20 tax rate .08 .11 .09 .11 public good expenditure .20 .11 .23 .12 percent of population 81 19 99 1 variable m ----- = 0 Mt Mym ----- = -5 Mt My m ----- = -9 Mt 17 no viable equilibrium found Table 3 Migration and Public Sector Impact of Fiscal Externalities: Similarly Progressive Tax Systems (a1 =a2 = 0 for all simulations), Greater Variance of Income Distribution Housing supply elasticity tax base responsiveness My region elasticity=1 elasticity=3 elasticity=9 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 region 1 region 2 tax rate .13 .14 .21 .21 .28 .28 public good expenditure .31 .43 .47 .61 .58 .73 percent of population 47 53 33 67 12 88 tax rate .09 .09 .12 .12 public good expenditure .22 .29 .27 .34 percent of population 47 53 30 70 tax rate .07 .07 .09 .08 public good expenditure .18 .22 .19 .25 percent of population 46 54 25 75 variable m ----- = 0 Mt Mym ----- = -5 Mt Mym ----- = -9 Mt 18 no viable equilibrium found no viable equilibrium found