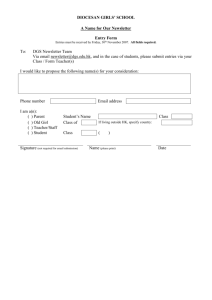

W G D S

advertisement