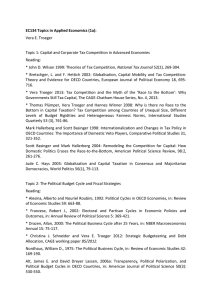

EC 134: Topics in Applied Economics (1a)

advertisement

© Vera E. Troeger EC 134: Topics in Applied Economics (1a) Week 7: Monetary Policy in Open Economies: Currency Unions and Fear of Floating 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Exchange Rates Determinants of Exchange-Rates Exchange-Rate Systems Exchange-Rate Regimes Pros and Cons of Fixed Exchange-Rates Mundell-Fleming theorem: The ‘Unholy Trinity’ Optimal Currency Areas “Fear of Floating” External Effects of Currency Unions © Vera E. Troeger Exchange Rates The Dollar/Euro Exchange Rate The Yen/Dollar Echange Rate What is an exchange-rate? An exchange rate is the rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another. In other words, it is the value of another country's currency compared to that of your own (and vice versa). What drives exchange-rates? © Vera E. Troeger …in the short run? we don’t know or: alternatively sentiments rumors expectations about the expectations of other investors events (shocks) … in the long run? the relative ratio of productivity growth and inflation expectations about productivity and inflation policies © Vera E. Troeger The Politics of Investor Confidence a depreciation of the domestic currency is caused by reduction in interest rate (c.p.) decline in economic growth (c.p.) increase in inflation (c.p.) decline in productivity growth (c.p.) high wage increases (c.p.) electoral success of left-wing party ? (c.p.) increase in government debt (c.p.) increase in government spending? (c.p.) country-specific demand shocks (c.p.) else? © Vera E. Troeger Exchange-Rate Systems Bretton Woods: Gold-Dollar Standard all countries pegged their currency to the dollar the value of the Dollar was expressed in gold US promised to exchange Dollars in gold all countries but the USA had to defend the parities problems: misalignment of exchange-rate, the Dollar © Vera E. Troeger since 1973 anything goes (most important currencies float to each other) problems: (surprisingly) high volatility © Vera E. Troeger Exchange-Rate Regimes Flexible Exchange-Rate the market decides on the relative value of the currency Managed Float in principle the currency floats, but the government may under certain circumstance intervene Fixed Exchange Rate Fixed to Key Currency (Dollar, Euro, Yen?) Fixed to Currency Basked the government(s) has/have the obligation to intervene important: parities, bandwidths © Vera E. Troeger Currency Board Value of Issued Money held in Reserves Dollarization Introduction of Dollar/ Euro/ Franc/ Pound as SOLE Means of Payments Currency Union Introduction of Common Currency (and common monetary policy) © Vera E. Troeger Why do some countries peg their currency, and other float? Advantages of stable exchange-rates: stable expectations no need to insure against exchange-rate risks (futures, hedges,…) low transactions costs to trade more trade (Andrew Rose) higher economic growth (?) Disadvantages of fixed exchange-rates risk of severe misalignment speculative attacks on exchange-rate peg reduction in monetary policy autonomy © Vera E. Troeger Paul Krugman on the Global System of Flexible ExchangeRates (http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/ExchangeRates.html) Exchange rates between currencies have been highly unstable since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, which lasted from 1946 to 1973. Under the Bretton Woods system, exchange rates (e.g., the number of dollars it takes to buy a British pound or German mark) were fixed at levels determined by governments. Under the "floating" exchange rates we have had since 1973, exchange rates are determined by people buying and selling currencies in the foreign-exchange markets. The instability of floating rates has surprised and disappointed many economists and businessmen, who had not expected them to create so much uncertainty. The history of the pound sterling/U.S. dollar rate is instructive. From 1949 to 1966, that rate did not change at all. In 1967 the devaluation of the pound by 14 percent was regarded as a major economic policy decision. Since the end of fixed rates in 1973 and 1991, however, the pound, on average, either appreciated or depreciated by 14 percent every two years. The instability of exchange rates in the seventies and eighties would not have surprised the founders of the Bretton Woods system, who had a deep distrust of financial markets. The previous experience with floating exchange rates (in the twenties) had been marked by massive instability. In an influential study of that experience, published in 1942, Norwegian economist Ragnar Nurkse argued that currency markets were subject to "destabilizing speculation," which created pointless and economically damaging fluctuations. During the fifties and sixties, however, as stresses built on the system of fixed exchange rates, both economists and policymakers began to see exchange rate flexibility in a more favorable light. In a seminal paper in 1953, Milton Friedman argued that the fear of floating exchange rates was unwarranted. Unstable exchange rates in the twenties, he maintained, were caused by unstable policies, not by destabilizing speculation. Friedman went on to argue that profit-maximizing speculators would always tend to stabilize, not destabilize, the exchange rate. By the late sixties Friedman's view had become widely accepted within the economics profession and among many businessmen and bankers. Therefore, concern over the instability of floating exchange rates was replaced by an appreciation of the greater flexibility that floating rates would give to macroeconomic policy. The main advantage was that nations could pursue independent monetary policies and adjust easily to eliminate payments imbalances and offset changes in their international competitiveness. This change in attitude helped to prepare the way for the abandonment of fixed rates in 1973. © Vera E. Troeger The instability of rates since 1973 has thus been a severe disappointment. Some of the changes in exchange rates can be attributed to differences in national inflation rates. But yearly changes in exchange rates have been much larger than can be explained by differences in inflation rates or in other variables such as different growth rates in various countries' money supplies. Why are exchange rates so unstable? Economists have suggested two explanations. One, originally expressed in a celebrated 1976 paper by MIT economist Rudiger Dornbusch, is that even without destabilizing speculation, exchange rates will be highly variable because of a phenomenon that Dornbusch labeled "over-shooting." Suppose that the United States increases its money supply. In the long run this must cause the value of the dollar to be lower; in the short run it will lead to a lower interest rate on dollar-denominated securities. But as Dornbusch pointed out, if the interest rate on dollar-denominated bonds falls below that on other assets, investors will be unwilling to hold them unless they expect the dollar to rise against other currencies in the future. How can the prospect of a long-run lower dollar and the need to offer investors a rising dollar be reconciled? The answer, Dornbusch asserted, is that the dollar must fall below its long-run value in the short run, so that it has room to rise. That is, if the U.S. money supply rises by 10 percent, which will eventually mean a 10 percent weaker dollar, the immediate impact will be a dollar depreciation of more than 10 percent—say 20 or 25 percent—"overshooting" the longrun value. The overshooting hypothesis helps explain why exchange rates are so much more unstable than inflation rates or money supplies. In spite of the intellectual appeal of the overshooting hypothesis, many economists have returned to the idea that destabilizing speculation is the principal cause of exchange rate instability. If those who buy and sell foreign exchange are rational, then forward exchange rates—rates today for sale of dollars some months hence—should be the best predictors of future exchange rates. But a key study by the University of Chicago's Lars Hansen and Northwestern University's Robert Hodrick in 1980 found that forward exchange rates actually have no useful predictive power. Since that study many other researchers have reached the same conclusion. At the same time, particular exchange rate fluctuations have seemed to depart clearly from any reasonable valuation. The run-up of the dollar in late 1984, for example, brought it to a level that priced U.S. industry out of many markets. The trade deficits that would have resulted could not have been sustained indefinitely, implying that the dollar would have to decline over time. Yet investors, by being willing to hold dollar-denominated bonds with only small interest premiums, were implicitly forecasting that the dollar would decline only slowly. Stephen Marris and I both pointed out that if the dollar were to decline as slowly as the market appeared to believe, growing U.S. interest payments to foreigners would outpace any decline in the trade deficit, implying an explosive and hence impossible growth in foreign debt. It was therefore apparent that the market was overvaluing the dollar. Overall, there is no evidence supporting Friedman's assumption that speculators would act in a rational, stabilizing fashion. And in several episodes Nurkse's fears of destabilizing speculation seem to ring true. © Vera E. Troeger What are the effects of exchange rate instability? The effects on both the prices and volumes of goods and services in world trade have been surprisingly small. During the eighties real West German wages went from 20 percent above the U.S. level to 25 percent below, then back to 30 percent above. One might have expected this to lead to huge swings in prices and in market shares. Yet the effects, while there, were fairly mild. In particular, many firms seem to have followed a strategy of "pricing to market" (i.e., keeping the prices of their exports stable in terms of the importing country's currency). Significant examples are the prices of imported automobiles in the United States, which neither fell much when the dollar was rising nor rose much when it began falling. Statistical studies, notably by Wharton economist Richard Marston, have documented the importance of pricing to market, especially among Japanese firms. The policy implications of unstable exchange rates remain a subject of great dispute. Refreshingly, this is not the usual debate between laissez-faire economists who trust markets and distrust governments, and interventionist economists with the opposite instincts. Instead, both camps are divided, and advocates of both fixed and floating rates find themselves with unaccustomed allies. Laissez-faire economists are divided between those who, like Milton Friedman, want stable monetary growth and therefore want to leave the exchange rate alone, and those who, like Columbia University's Robert Mundell, want the discipline of fixed exchange rates and even a return to the gold standard. Interventionists are divided between those who, like Yale's James Tobin, regard exchange rate instability as a price worth paying for the freedom to pursue an activist monetary policy, and those who, like John Williamson of the Institute for International Economics, distrust financial markets too much to trust them with determining the exchange rate. In general, sentiment among both economists and policymakers has drifted away from belief in freely floating rates. On the one hand, exchange rates among the major currencies have been more erratic than anyone expected. On the other hand, the European Monetary System, an experiment in quasi-fixed rates, has proved surprisingly durable. Taking the long view, however, attitudes about exchange rate instability have repeatedly shifted, proving ultimately as poorly grounded in fundamentals as the rates themselves. © Vera E. Troeger The Open Economy Trilemma: Mundell-Fleming Theorem How are fixed exchange rates and monetary policy related? Mundell-Fleming theorem (unholy trinity): Government can only reach two of the following three policy goals simultaneously: stable exchange rates absence of capital controls monetary policy autonomy With unarguably high capital mobility governments face the dilemmatic choice between monetary policy flexibility and stable exchange rates. The Mundell-Fleming theorem dominates current research in Comparative Political Economy, and… © Vera E. Troeger … the ideology of the IMF “So what did our experience in the 1990s teach us about delivering growth and prosperity? Several important lessons stand out. First and foremost is the crucial importance of a flexible exchange rate regime. Fixed exchange rate regimes pose significant challenges because they mean fiscal and monetary policies must always be consistent with the exchange rate regime and subordinated to it. The countries affected by capital account crises were all hampered in their initial response to trouble by fixed or heavily managed exchange rate regimes.” Anne O. Krueger, First Deputy Managing Director of the IMF, May 2006 “While most of us, faced with an unconstrained choice, would opt for arrangements that promise greater exchange rate stability, I think we must also recognize that the global environment is even less hospitable to such a system today than it was 25 years ago. Realistically, there is no alternative to floating exchange rates […]” Horst Köhler, Managing Director of the IMF, January 2001 © Vera E. Troeger Currency Unions Benefits of intensified trade and loss of monetary independence On the one hand, members of currency unions benefit since a joint currency decreases trading costs induced by exchange rate risks and hence generates efficiency gains. On the other hand, governments of member states have to surrender monetary policy autonomy to the union’s central bank and can no longer tailor their policy to country specific exogenous shocks Price and monetary stability Credibility beyond fixed exchange-rate system One currency decreases transaction costs for trade Else? Alesina/ Barro 2002 © Vera E. Troeger Optimal Currency Areas One currency? No exchange rate risks Simultaneity of Economic Business Cycles? Trade Co-movements of output and prices Impact of CU on trade and co-movements Does market integration decrease the optimal number of currencies? © Vera E. Troeger EXAMPLE: GREXIT The Euro-crisis, Eurozone and Grexit (Iversen/Soskice) Institutionally speaking, the Eurozone is not an optimal currency area: ▪ the main problem is a deep structural-institutional imbalance in the Eurozone ▪ Eurozone institutions were built around a northern European (NE) model of capitalism, which is not compatible with southern European (SE) institutions. KNOWN AT THE BIRTH OF EMU ▪ Reforms are blocked by insiders in the South. ▪ Major debt restructuring is blocked by voters in the North (esp. Germany) ▪ Yet Grexit (and a wider breakup) is too costly for all. This creates a “curse” of a large bargaining space, resulting in a protracted war of attrition (and continued austerity). © Vera E. Troeger NE export model of capitalism ▪ Export-sector led growth based on coordinated wage bargaining, a strong nonaccommodating CB, and effective training institutions ▪ Wage restraint is reinforced by inter-sectoral compression ▪ Net result: high competitiveness and demand for skilled workers. Demand is accommodated through effective training systems, e.g. Germany ▪ Institutional equilibrium is under-written by a political compromise between export employers, skilled unions, and at least a portion of the low-skilled (who benefit from training) ▪ Empirical correlates: high competitiveness and high domestic price levels © Vera E. Troeger SE dualism “model” ▪ Division between a formal sector with strong but uncoordinated unions, high protection and wages; and a large informal sector with weak unions, and low protection and wages ▪ Macroeconomic policies were (before the Euro) mildly inflationary and linked to occasional devaluations (plus capital controls) ▪ Inter-sectoral inequality is high and demand for skilled labor low, with underdeveloped training systems ▪ Institutions are under-written by an insider political coalition that largely excludes workers in the informal sector, as well as export interests. ▪ Empirical correlates: Low competitiveness and low domestic price levels © Vera E. Troeger Two clusters of euro-zone countries © Vera E. Troeger Effect of common currency ▪ NE: Large gain (growth) from fixed exchange rates and real depreciation of exports to SE. New investment opportunities in SE as devaluation risk disappears (at least in short term). ▪ SE: Short- and medium-term gain as capital flowed in from the surplus countries. But eventually massive loss from real appreciation and steeply rising debt costs b/c of the risk of depreciation (euro exit). No off-setting effects of the ECB. © Vera E. Troeger Trade divergence © Vera E. Troeger The southern European risk premium on long term interest rates from the Maastricht Treaty to 2011 © Vera E. Troeger The trade deficit and long term interest rates in 2011 © Vera E. Troeger Solutions? ▪ (1) Breakup of the euro: long-term viability, but huge short- and medium-term costs because of uncertainty, capital flight, etc. Costs so high that a bargain to avoid GREXIT (and keep SE as a whole) always seems feasible ▪ (2) Institutional reform in SE: flexibilize labor markets and break down insider protections better downward adjustment of wages and more balanced trade. But again huge short-term costs that are blocked by insiders as long as (1) is ruled out. ▪ (3) Large transfer from north to south (deep debt restructuring) – a “Marshall plan” for SE. SE would recover and buy NE exports again. Sustainable at least in the medium run, but blocked by German voters as long as (1) is ruled out. ▪ (4) Japanese-style austerity. (Or very gradual recovery as US and China markets pick up). © Vera E. Troeger The curse of a large bargaining space: War of attrition © Vera E. Troeger Long run: Optimistic scenario © Vera E. Troeger Long run: Pessimistic scenario ▪ Continued austerity unacceptable to France and Italy Germany given an ultimatum: Either total break-up or acceptance of much more accommodating policies: Governments allowed raising their deficits and ECB engaging in large-scale quantitative easing. ▪ Already: France blowing through the deficit ceiling – inaugural visit of Manuel Valls in Germany ▪ Problem: If this really happens North (Germany) is likely to prefer a break-up Thoughts? Predictions? © Vera E. Troeger Fear of Floating No small country enjoys monetary flexibility and all governments must maintain a tight connection to the interest rate of the relevant base economy. (Calvo/ Reinhart) Countries with flexible exchange-rates do often not enjoy full monetary policy autonomy but rather take into account the exchange-rate effects when making monetary policy choices. Accordingly, most governments are forced to bring their own monetary policy in line with the relevant base country. Exchange-rate pass-trough © Vera E. Troeger The UK outside the EMU Insider vs. Outsider Perspective Benefits and Costs of Currency Unions Stable currency and monetary policy (trade, investment and borrowing) vs. Monetary Policy Autonomy esp. during economic crises Necessary condition for CU: similar economic and labor market institutions and economic business cycles © Vera E. Troeger UK: £ and flexibility © Vera E. Troeger Bank Cross-Border Position: Assets in bn $ Currency Denomination of BIS reporting Bank’s Cross Border Positions (Assets), 1977-2004 (BIS 2004) 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 Dollar Euro 2000 Yen 1000 0 Q3 1982 Q3 1987 Q3 1992 Year Q3 1997 Q3 2002 © Vera E. Troeger © Vera E. Troeger 0.8 0.8 0.6 0.6 effect of US interest rate effect of Ger/ EMU interest rate Findings: The Impact of the EMU and US MP on Non-EURO EU Countries 0.4 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.0 0.0 -0.2 -0.2 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 year figure 1a: the impact of EMU interest rate on non-EURO EU countries' interest rate 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 year figure 1b: the impact of US interest rate on non-EURO EU countries' interest rate © Vera E. Troeger Dependent variable: changes of real interest rates Mean Equation: Intercept Level of Real Interest Rate Δ Real Interest Rate 80-90 Δ Real Interest Rate Ger/Euro, 90-94 Δ Real Interest Rate zone, 94-99 Δ Real Interest Rate zone, 99-02 Δ Real Interest Rate zone, 02-05 Δ Real Interest Rate 80-90 Δ Real Interest Rate 90-94 Δ Real Interest Rate 94-99 Δ Real Interest Rate 99-02 Δ Real Interest Rate 02-05 Domestic Growth Ger, EuroEuroEuroUSA, USA, USA, USA, USA, Growth Germany/Eurozone Growth USA Domestic Unemployment FE Model 4: EU, trade weighted (UK, DNK, SWE) Model 5: EFTA, trade weighted (NOR, SWI) Model 6: NonEuropean, trade weighted (AUS, NZ) Model 7: CAN trade weighted -0.085 (0.066) 0.037*** (0.012) 0.066 (0.114) 0.032 (0.079) 0.244*** (0.092) 0.324*** (0.102) 0.601*** (0.101) -0.067 (0.044) 0.137*** (0.055) 0.066 (0.049) 0.025 (0.021) 0.008 (0.020) -0.296** (0.123) 0.087*** (0.020) 0.278*** (0.085) 0.044 (0.058) 0.026 (0.108) 0.390** (0.200) 0.361** (0.185) 0.033 (0.032) 0.201*** (0.039) 0.174*** (0.061) 0.043* (0.027) 0.112*** (0.031) -0.120 (0.291) 0.035 (0.037) -0.477 (0.385) -0.260 (0.195) 0.113 (0.173) 0.113*** (0.029) 0.033 (0.056) 0.029 (0.050) 0.367* (0.197) 0.241** (0.124) 0.069 (0.237) 0.207 (0.165) -0.023 (0.193) 0.037** (0.016) -0.069 (0.091) 0.130 (0.203) 0.237 (0.252) 0.007 (0.056) 0.132 (0.123) 0.491*** (0.056) 0.738*** (0.185) 0.624* (0.376) 0.718*** (0.163) 0.934*** (0.181) -0.002 (0.008) -0.003 (0.006) 0.010 (0.007) 0.009 (0.006) 0.019 (0.024) 0.003 (0.008) -0.011 (0.015) -0.002 (0.009) 0.029*** (0.010) -0.003 (0.009) -0.001 (0.022) 0.032 (0.023) -0.021** (0.011) Yes -0.012 (0.015) Yes -0.033 (0.030) Yes -0.028 (0.020) No © Vera E. Troeger More Research: Monetary Policy Flexibility in Floating Exchange Rate Regimes Which factors determine the de facto monetary policy autonomy of (small) open economies with flexible exchange rate systems? 2 Explanations: Trading relations with key currency areas Currency denomination of bank cross border assets © Vera E. Troeger Trade and Cross-border Banking Assets De facto monetary policy autonomy is limited by the influence of monetary policy on the exchange-rate and (thus) on the current account. This constraint is stricter if the amount of imports of goods and services from the key currency area is large and the share of assets denominated in the base currency is large. © Vera E. Troeger A Model: open economy The optimal policy choice depends on a) the degree to which governments maximize output and consumption by counterbalancing exogenous shocks and b) the exchange rate effects of domestic monetary policy settings: Lg Ct t t zb E / I 2 The exchange rate to a key currency depends on a) asset shares denominated in the key currency and b) the difference between domestic and foreign interest rate policy: Ab zb A i i t b b b i i z A i i t 1 t t 1 b t t Imported inflation depends on the amount of goods imported from a particular key currency area Ib I E t t 1 it it 1 zb Y I © Vera E. Troeger Exchange-Rate Effects A reduction in interest rates in country i leads to a depreciation of i’s currency and thus an increase in the prices of imported goods, ceteris paribus. The more the domestic economy imports from the key currency area the higher is the imported inflation. The specific (bilateral) exchange-rate effects are largely determined by the decision of capital owners which currency they choose as ‚safe haven‘ for their assets. Exchange rate effects enforced by import and asset shares shape the optimal domestic monetary policy decision of governments © Vera E. Troeger Optimal domestic policy for different values of the interest rate in the base country and import share of the key currency area: 4.0 st rate 3.5 optimal domestic intere 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 at e tr es 0.5 te r 0.4 0.6 e of 0.7 impo 0.8 rts fr to al 0.9 om b l imp 1.0 a se orts coun and dom try estic GDP in shar 0.3 se 0.2 ba 1.0 0.0 0.1 5.0 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 © Vera E. Troeger Optimal domestic policy for different values of the interest rate in the base country and assets denominated in the base currency: 4.0 st rate 3.5 optimal domestic intere 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 es tr 0.5 te r 0.4 0.6 e of 0.7 asse 0.8 ts de n i n ba omin 0.9 1.0 se cu ated rrenc y in 0.3 shar se 0.2 ba 0.0 0.1 5.0 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 at e 1.0 © Vera E. Troeger Optimal Monetary Policy in an Open Economy Optimal monetary policy in open economies depends on: a) the strengths and idiosyncrasy of exogenous shocks, b) the effect of monetary policy on import prices and inflation, c) the effect of cross border assets on the exchange-rate to the key currency. Governments have strong incentives to stabilizes the exchange rate to the currency of their main trading partners. © Vera E. Troeger Predictions of the Model Small countries with floating exchange rate systems enjoy only limited monetary policy flexibility. The impact of the monetary policy of a key currency area depends on the relative amount of imported goods and services from this area. The effect of the key currency’s monetary policy hinges on the amount of assets denominated in the key currency. © Vera E. Troeger Data Monthly interest rates of 38 countries from Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia, Africa, and Latin America (discount and lending rates): • 45 % crawling or moving bands (with both appreciation and depreciation possible) • 55 % free or managed float Time period: 1980 – 2004 Monthly import shares from EMU and US (IMF direction of trade statistics) Currency denomination (EURO or US Dollar) of national banks’ cross border assets (Bank for International Settlements) – for 20 countries Controls: export share, CBI, capital mobility, elections, GDP growth, unemployment © Vera E. Troeger Africa Asia Egypt Morocco South Africa Hong Kong Indonesia Japan Korea Malaysia Philippines Thailand Europe Latin America Argentina Bolivia Brazil Chile Colombia Mexico Peru Uruguay Venezuela Oceania North America Canada Austria Australia (Belgium) New Zealand Denmark Finland France Greece Iceland Ireland Italy (Luxembourg) Netherlands Norway Portugal Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom Luxembourg and Belgium are not part of the analysis since they follow pegged regimes throughout the period under observation © Vera E. Troeger Region Europe Latin America Asia Africa Australia and New Zealand Canada Region Europe Latin America Asia Australia Canada Share of cross border assets EURO US$ 0.29 0.40 0.07 0.76 0.07 0.54 0.02 0.70 0.02 0.80 Share of Imports of Goods and Services EMU US 0.48 0.07 0.17 0.30 0.16 0.10 0.10 0.47 0.34 0.12 0.07 0.65 Before 1999 EURO 0.22 0.05 0.02 0.02 US$ 0.44 0.50 0.80 0.83 After 1999 EURO 0.48 0.07 0.11 0.03 0.02 US$ 0.29 0.76 0.62 0.53 0.73 .8 .4 .6 US$ .2 Euro JPY CHF GBP 0 % of assets hold in foreign currencies © Vera E. Troeger 01/80 05/83 09/86 05/93 01/90 Date 09/96 01/00 05/03 © Vera E. Troeger Econometric Model real interest rates: governments/monetary authorities are able to control real interest rates first differenced data: methodological: unit roots; theoretical: short term adjustments Garch(1,1) specification: control for time-dependent error variance – increase efficiency Main IV: changes in EMU/US real interest rates weighted by import/ asset shares Spatial lags: evenly weighted or weighted with distances/import share: no significant effect (not reported) © Vera E. Troeger DV: monthly change of real CB interest rate Intercept Real CB interest rate (t-1) Model 1.1 Flex WKS 0.076 (0.119) -0.044*** (0.004) Δ real interest rate GER/EMU 0 . ( Δ r Δ r w e e e i a a g l i l h t e a i e n t n t d e e r w e r i g h l t i i e d x p h n t i s T o t a l e o s h a r r e t h r t r e t t u e U e r S E o - M 0 U A s s . 0 ( 0 0 e t e g i s l a t i v 3 . * 0 4 ( t r U a t S e e U D S A 0 s s e . t ( * 9 7 * 8 9 * . ( * 8 * . 1 8 0 * * . 1 5 3 ) 2 6 0 ) - 0 x e c u t i o e v t e e 4 ( 0 ( 0 0 . 9 8 0 . 9 * 1 * 4 * 0 0 . ) ( a l i m p o r t s - 0 l e c t i o n . 0 . 0 2 0 ) ( 8 8 o l o u r o f t h e e G D G r U C C a p A n i t P P e a l m M Δ * A P Δ * e l e c o t v i o e e a i l i C i t n E s 0 n m e n t B B I Δ * r G C B I Δ * r e M V a a n y t 0 ( e r . t a r i a R l C e A s P i n r t r a t n c e H R C t s e t r M e E r a t e U S q e s t r a t ( L P o r g o b l i e s h c l * 4 0 0 . 0 ( . . ( 8 . 4 3 0 . * 1 * 1 3 0 0 * 4 * 0 1 . ) ( ) ( 0 3 0 . 0 . 0 1 1 0 . 0 2 1 0 0 1 - ) * * 7 0 . . . ( 8 . 4 3 0 . * 1 * 1 3 0 0 ) 4 0 0 ( * 5 . ( * 9 8 0 ) 0 7 1 * 0 2 * 1 * 4 * 1 6 9 ( 0 . . 0 t r a t e U S a t i * ) . i i - * * 7 6 0 0 . 0 ) * 5 . ( * 9 8 0 ) 0 7 1 * 0 0 1 Model 1.5 - Hyperinfl 0.014 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) . ( 0 ( 0 0 ) . 7 * 1 4 * 1 3 * 3 6 ) * 1 8 2 * * . 1 5 0 ) 2 9 * . 7 ) 1 . ) ( ) ( 0 3 0 . 2 * 1 * 4 * 1 1 . ) ( ) ( 0 3 0 . 0 * 1 * 4 * 9 ) h i 0 . ( 0 . . . o o ) ( d - 0 . ) ( ) ( ) 5 ) * * 3 ) ( * ) 0 3 1 . . 0 ( - 0 1 1 ( ) ( 3 0 . 1 7 9 . 0 0 1 0 . 0 2 5 0 3 0 . 0 2 3 0 . 0 4 6 2 7 0 . 0 4 9 0 . 1 6 2 0 . 0 5 9 0 . 1 8 5 . 0 0 4 0 . 0 2 6 ( . 0 2 9 . . 2 1 9 0 0 6 ( 2 0 0 . 1 0 7 0 . 0 1 2 0 . 0 0 1 0 . 0 7 * * 0 1 0 . 0 0 3 ) ( 0 . 0 . 0 2 4 ) ( ) ( 0 . 0 2 3 0 - 0 ) ( ) ( * - . 0 ( ) ( 0 9 6 * 0 . 0 2 3 0 . 0 4 6 6 * . 0 7 0 . 0 4 9 0 . 1 6 2 . 0 5 9 . - 0 . 0 . 1 8 5 . 0 0 4 0 . 0 2 6 1 1 * 0 * 7 0 . 0 5 5 ( 0 . 0 5 0 . 2 4 1 0 1 0 0 . 1 2 8 ) ( 0 . 1 5 7 ) ( ) ( . 7 0 ) * ( 0 0 * ) * ) - . ) * ) 0 ) * 0 - * 3 ( * ) * 0 0 * 3 0 0 . ) * 0 4 ) 1 3 ) 2 0 ( 0 * 0 0 ( * 9 4 . * 0 3 2 0 ) 2 2 0 ( ) 3 0 . - ) 3 0 . ) 0 . . 0 * ) 4 ( * ) 1 4 ) * ( 0 . 0 3 ) . . 0 1 0 0 . 1 . ( 0 0 0 0 * 2 9 - ) 1 4 8 0 * 6 2 ( * 4 0 ) * 0 0 1 2 0 0 . . . * 0 9 0 0 0 * * . ( ) 4 0 0 9 0 - ) 6 0 - 0 * . . ) 6 . . * 0 0 ( * 9 0 0 0 ) 2 2 0 8 ( * 3 3 0 0 ) 7 8 ( * 0 0 . . 2 6 2 - * 0 ( 7 0 * 0 ( 0 0 0 1 * 0 0 0 0 . 1 3 . . . ) . 0 0 0 * 0 3 . 6 1 ( 5 . 4 2 0 0 ( * ) 4 0 0 0 0 ) * 0 . ) 2 1 * . 8 7 . . 2 9 0 0 0 0 9 ( . . . 2 1 * * 0 0 8 5 9 . 0 6 0 0 * 3 0 0 0 * 5 . - 0 . 0 0 7 2 7 0 ( * 8 0 8 0 ) 8 1 7 8 . ) 0 0 ( * 3 2 0 0 2 - 7 0 0 * . 3 7 0 0 - 1 0 1 ( 5 6 2 . 1 0 0 . . 2 ² 4 0 1 * 0 0 . . 0 * 0 . 1 4 0 0 ( 0 0 . . 9 3 * ) ) 3 0 . 1 8 5 0 . 0 0 1 0 . 0 2 8 ) ) : ² h 0 . 0 ) * 7 1 0 0 6 0 . 0 ( n * 2 0 - o 1 4 0 - ( 9 0 . 0 - . 3 0 0 0 2 . 0 . 0 * ( 1 1 0 ) 7 ) * ) 0 0 3 2 2 * . 0 4 2 * . ( * 0 0 0 0 ( * 3 0 6 ) * 7 0 0 1 1 . . 2 - 0 ( . 6 7 0 * 2 6 8 0 * 0 0 . * 3 0 * . 0 * 0 0 2 0 - 2 8 7 0 . * 0 . 8 8 * 7 1 . 0 1 * . * 0 . ( * 8 ) 6 3 0 ) 0 . ( 0 9 0 . 8 8 0 . 3 8 0 * ) * 0 5 0 * 0 0 3 3 2 0 2 e 7 1 ( 7 0 - u c > k 9 . ) 0 . . ( 2 t 1 d 9 0 0 e 2 t 1 1 l * ) . ( N a * 6 0 0 ( W 2 5 ( . 0 U r 1 H 5 1 - ) 1 0 - t 1 e . * . 3 0 ( * 4 . ( e - n t * 7 0 1 ) U e E 1 C A i / 3 0 0 0 I l R A A G e E * ) 1 0 0 ( C * 6 . . t h e M n 6 0 s n r t m l i / w y l R o o b a E r l o r G C p * 0 0 ( G 5 1 . 0 - 5 ( C 8 . . ) ( E 3 0 Model 1.4 +Democ 0.027 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) s t ( L 5 . Model 1.3 + Capmob. 0.027 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) s s / a a E r s r t h a t s t e w e e w s Δ r 3 0 Model 1.2 Flex WKS 0.030 (0.128) -0.048*** (0.005) 2 8 * 2 ( 9 p 6 < - = 0 . 0 1 ; 9 6 0 . * 0 8 0 * 0 7 . 0 2 3 0 6 * * p < 0 . ( * 8 ) 1 3 0 ) 0 . ( 1 0 0 . 8 7 0 . 3 4 0 * ) * 0 5 8 * 0 . 2 1 = 2 ( 6 0 9 . - 0 5 ; * p < 2 = 2 9 0 . 2 3 0 . 8 6 * 0 8 0 0 . ( * 8 ) 5 7 0 ) 0 . ( 1 0 0 . 8 7 0 . 9 . 0 5 * ) * 0 2 1 * 0 4 5 * 0 . 2 7 1 2 ( 9 - 2 2 2 9 0 . 3 * 0 8 6 * 0 8 . 0 5 0 . ( * 8 ) 5 7 0 ) 0 0 9 0 . . ( 8 6 0 . 9 2 0 * ) * 0 4 5 * 0 . 2 7 1 2 ( 9 - 1 7 0 . 7 * * 0 9 1 * 0 2 3 . 0 0 * ) 0 2 0 * ) * 1 2 1 7 6 0 . 6 6 0 ) 2 9 8 © Vera E. Troeger DV: monthly change of real CB interest rate Intercept Real CB interest rate (t-1) Model 1.1 Flex WKS 0.076 (0.119) -0.044*** (0.004) Δ real interest rate GER/EMU 0 . ( Δ r e a l i n t e r e s t r a t e U S - 0 r w e i e a g l h i t e n t d e w w e r i g e a h t l i e h n d t i o t a l e x p o r t t r r e a e u t e r r U E o a S e t t M A U s s t e g i s l a t i v e 4 ( 0 2 0 . 9 8 0 . * 9 7 . . t e U D S A 0 s s e t . ( * * 8 9 0 . ) * ( * * 1 6 8 ) 8 0 * * 1 5 3 ) - 0 x e c u t i v e o t e e ( o l o u r o f t h e G 0 . 4 1 . . ( 5 3 0 . 9 9 0 . * * 0 6 0 0 9 1 * 4 * 0 * 0 . ) ( a l i m p o r t s - l e c t i o n 0 0 . . 0 0 2 8 8 5 - ) ( s l e c t i o n s 0 . ( C 8 . ( E 3 * 6 3 0 . ) * ( * * 1 7 4 ) 5 2 * * 1 5 6 ) - 4 0 0 . 0 ( 0 . ( . 8 1 1 3 0 . 4 3 0 . 0 3 0 . * - ) * 5 . ( * 9 8 0 ) 0 7 1 * 0 0 1 * Model 1.4 +Democ 0.027 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) * 7 0 ) 0 0 . 0 ( * 4 . ( . 8 1 1 3 0 . 4 3 0 . 0 3 0 . * - * 7 0 . 1 * 1 3 . . ( 7 4 0 0 ) 0 . ( * 6 0 ) * 5 . ( * 9 8 0 ) 0 7 1 * 0 0 1 * Model 1.5 - Hyperinfl 0.014 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) 2 0 . 0 3 0 . * 3 6 * ) * * 1 9 7 ) 8 2 * * 1 5 0 ) 7 1 * 4 * 0 * 1 ) . ( 2 1 * 4 * 1 * 1 ) . ( 2 1 * 4 * 1 * ) 1 . ( 0 1 * 4 * 9 * ) s ( L . 0 0 e 0 3 Model 1.3 + Capmob. 0.027 (0.134) -0.047*** (0.005) s s r / a E h s r h a t h s t e w s T e i s Δ r 5 . ( Δ 3 Model 1.2 Flex WKS 0.030 (0.128) -0.048*** (0.005) o v e r n m e n t 0 0 0 6 6 0 . 0 8 7 0 . 0 1 1 0 . 0 2 1 2 1 0 . . ( . 0 0 . 1 * - ) ( ) * ( * 0 4 2 ) 2 2 * * 0 1 1 ) 0 . ( 0 0 7 0 0 . 0 8 8 0 . 0 0 9 0 . 0 2 1 2 9 0 . 0 ( . . 0 9 0 0 . * 4 2 0 ) ( ) * 6 1 1 - ( * ) 0 . ( * 1 0 ( 0 7 0 0 . 0 8 8 0 . 0 0 9 0 . 0 2 1 2 9 0 . 0 ) . . 0 9 0 0 . * 4 2 0 ) ( ) * 6 1 1 - ( * ) ( ) ( . 0 4 2 0 . 0 8 9 0 . 0 0 6 0 . 0 2 1 - * 1 0 0 . 0 4 ) ) 4 0 . 1 0 7 0 . 0 1 2 0 . 0 1 1 ) ) © Vera E. Troeger GDP Growth 0.012*** (0.002) 0.007** (0.003) 0.016 (0.019) Unemployment Capital Mobility (CAP) CAP* Δ real interest rate G C A P Δ * E r e R a / l i E M n t - U e r 0 ( e s t r a t e U S 0 0 B I - B I Δ * r G C B I Δ * r a e r i a a R i / l i n c n 0 C t e r M t e e s t r a t . r ( e s t r a t e U 2 - U S 0 - ( - e E q ( u a t i o n 0 L o r g o ( 2 t 1 1 l b l i 1 * * 0 4 2 ) 6 * 7 0 - . - 0 0 ( ) 0 ( 7 ) 8 5 * * 0 4 3 ) 5 0 . * 8 . 0 - 7 . * 3 6 0 3 7 2 ( ) . 5 0 0 0 0 7 . . ( ) 1 0 0 0 * 0 0 5 6 1 . ( * 0 4 2 . 0 . 1 0 0 . 0 8 7 0 . . N P 9 . 0 . ( ( ) 0 7 0 2 . * - 0 ) 1 1 0 . 1 7 9 0 . 0 0 1 0 . 0 2 5 0 9 0 . 8 8 0 . * 3 9 0 . 0 2 3 0 . 0 4 6 2 6 4 0 7 5 0 . 0 4 9 0 . 1 6 2 0 ( . 0 - 9 0 ) . ( ) * - 0 ) 0 . 1 8 5 0 . 0 0 4 0 . 0 2 6 1 0 0 . 8 7 0 . * 3 9 0 . 0 2 3 0 . 0 4 6 2 6 4 0 7 5 0 . 0 4 9 0 . 1 6 2 0 ( . 0 9 0.013*** (0.003) 0.010*** (0.003) 0.024 (0.023) - 0 ) . ( ) ( * . - * * 0 ( ) 6 0 . 2 9 . ( ) 0 0 ( * . - * * 0 ( ) 6 0 . 3 9 . ( ) 0 0 ( 2 6 2 0 ( * 3 1 . * - 0.013*** (0.003) 0.007** (0.003) 0.032* (0.020) * - 0 ) ( 2 0 . 1 8 5 0 . 0 0 4 0 . 0 2 6 1 0 0 . 8 7 0 . ( 7 * * . 0 4 0 0 . 0 5 5 0 . 0 5 0 2 1 1 0 7 9 0 . 1 2 8 0 . 1 5 7 . 0 ) * . 0 * ) * 0 - ) 4 0 . ( ) 1 3 * ) ) 3 0 . 1 8 5 0 . 0 0 1 0 . 0 2 8 0 9 0 . 8 6 0 . ) 2 d c h > k e c l i i ² h h i o 2 ² o ) ( d 0 2 5 ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) : 2 t 1 1 a 7 1 . - 3 . 0 0 0 0 . 0 6 3 . 0 0 0.013*** (0.003) 0.007** (0.003) 0.032* (0.020) t 1 H W . 0 e H R n E 1 C A l R A A G a E M V e 0 0 ( C . . ( C . 0.014*** (0.003) 0.007** (0.003) 0.028* (0.018) - 2 0 0 . 1 * 0 * 0 8 8 * 0 8 7 . 0 1 0 . ) ( * 0 . ) ( 3 8 0 * * 0 5 3 3 2 . 2 6 3 0 ) 8 9 2 ( 6 - 2 3 9 0 6 0 . 0 * 0 8 0 * 0 8 7 . 0 6 0 . ) ( * 0 . ) ( 3 4 0 * * 0 5 8 * . 2 1 3 0 ) 1 6 2 ( 9 - 2 2 2 0 9 0 . 3 * 0 8 6 * 0 8 8 . 0 5 0 . ) ( * 0 . ) ( 9 2 0 * * 0 4 5 * . 2 5 7 0 ) 7 1 2 ( 9 - 2 2 2 0 9 0 . 3 * 0 8 6 * 0 8 8 . 0 5 0 . ) ( * 0 . ) ( 9 2 0 * * 0 4 5 * . 2 5 7 0 ) 7 1 2 ( 9 - 1 7 0 . 7 * 0 * 0 9 1 * 0 3 . 0 0 ) * 2 ) 6 6 0 ) 0 2 0 * * 1 2 1 7 6 . 2 9 8 © Vera E. Troeger DV: monthly change of real CB interest rate Intercept Real CB interest rate (t-1) Model 2.1 Flex WKS -0.216*** (0.030) -0.085*** (0.001) Δ real interest rate GER/EMU 0 . ( Δ r e a l i n t e r e s t r a t e U S - 0 w e r i g e h a t l e w e i r g h r e a t e o t a l e m l i x n t t h t m E e h s I t r r e r t t I m o s h e i o p e t w r r i o d e t w f T n d f Δ i s / p o t e r a p t t o U o E M t s U h 1 a r e s . ( e U r t i m S s h 0 a r e s . ( e g i s l a t i v e e l . 5 0 * 5 1 6 1 1 0 . 5 3 0 . 1 1 5 0 . 4 2 0 0 . 4 3 0 0 3 * 7 * - 0 0 0 ) * 0 ( * . - ) * 0 1 * 3 6 0 * . ( * 1 . ) ( 0 * * * 0 . ) ( a l p o r t s e c t i o n - x e c u t i v e e l e o l o u r o f t h e G o 0 0 0 . 6 0 0 . 9 8 0 . 9 5 9 0 ) . ( s 0 . c t i o n s - 0 8 1 0 7 0 ) * ( * 8 1 * ) * ( * 8 * 9 9 1 v e r n m e n t - 0 0 ) * . ( * 4 7 . 1 0 0 . 2 0 . ( 0 0 . ( C . 2 0 ( E . 0 . 0 5 3 0 . 1 3 6 0 . 0 3 6 0 . 1 6 0 5 0 0 . 3 6 0 . 7 0 ) ( 0 . 1 6 3 0 . 1 1 1 - ) * 8 Model 2.4 +Democ 0.284*** (0.092) -0.024*** (0.002) ( * 2 0 * 0 . ) ( . 0 . 4 5 0 . 4 2 0 . 0 6 1 0 0 ) . ( - 9 * ) * 8 ( * 2 0 ( . 0 7 8 * * 1 1 5 ) . 0 . 7 1 0 . 4 4 0 . . ) 2 0 9 2 4 Model 2.5 - Hyperinfl 0.143 (0.106) -0.051*** (0.002) 0 4 1 2 4 5 9 0 ) * 8 * * 0 ) * 2 0 ) . ( 4 1 * 3 * 5 * 0 . ) ( 4 1 * * 2 * 7 0 . ) ( 3 1 * 3 * * 3 ) S ( L 0 8 Model 2.3 + Capmob. 0.264*** (0.099) -0.023*** (0.002) U r e t t M m h a 3 . ( Δ 2 Model 2.2 Flex WKS 0.813*** (0.057) -0.096*** (0.001) 0 0 0 0 0 2 . 0 * 3 5 1 . 6 7 * 2 3 0 8 ( * ) * 7 . ( ) * * 0 * 4 * - ) * 1 9 * * ) 2 * . 0 7 0 0 . 0 1 4 0 . 0 1 7 0 0 - ( 0 0 - ( 2 . . 0 0 0 0 . . 5 8 0 0 - 0 ) 2 ( - ) . ( ) 1 0 0 * 0 ( ) ( 2 5 * * 0 . 0 6 4 0 . 0 0 2 0 . 0 1 3 . 1 9 2 2 5 8 * * ) . 0 3 9 0 . 0 0 2 0 . 0 0 8 0 ( ) ( ) ( ( 0 0 - 1 . . * ) . 0 0 * 0 - . 0 3 3 * 0 7 4 ) 4 2 * * 0 1 8 ) . 0 7 5 0 . 0 8 1 0 . 0 1 2 0 . 0 1 0 ) ) © Vera E. Troeger Results Governments adjust their interest-rate to the monetary policy in the key currency area even if they have implemented a flexible exchange-rate system. De facto monetary policy autonomy is lower if countries import more from the key currency area capital owners hold their asset in the key currency Governments in small, open economies face a dilemmatic choice between stabilizing the exchange rate to this key currency and using monetary policy to stimulate the domestic economy. The smaller and more open the economy is, and the more synchronized its business cycle with that of the key currency area, the more important becomes exchange-rate stability and the less important monetary policy autonomy.