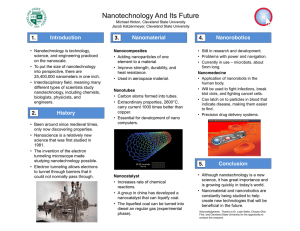

AE U R Nanotechnology - Ethical and

advertisement