www.XtremePapers.com

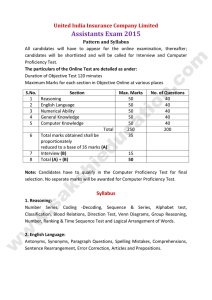

advertisement