9782 PRINCIPAL COURSE RUSSIAN for the guidance of teachers

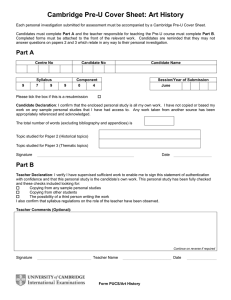

advertisement