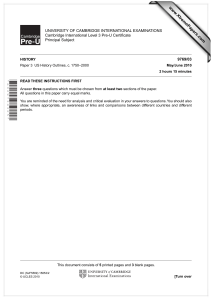

MAXIMUM MARK: 90 www.XtremePapers.com Cambridge International Examinations 9769/04

advertisement