9779 PRINCIPAL COURSE FRENCH for the guidance of teachers

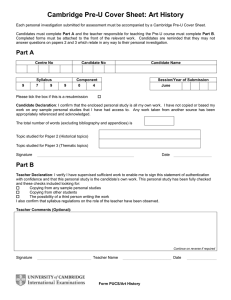

advertisement