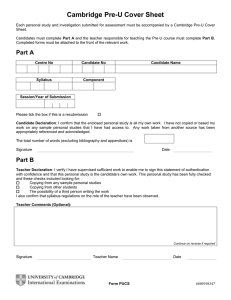

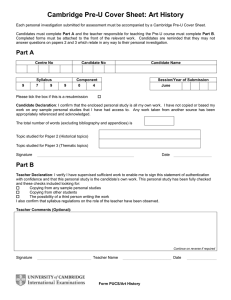

Example Candidate Responses Cambridge International Level 3 Pre-U Certificate in

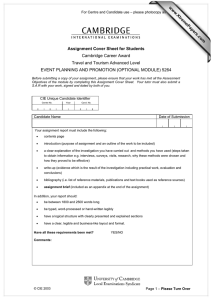

advertisement