GENERAL TABLE OF CONTENTS www.XtremePapers.com

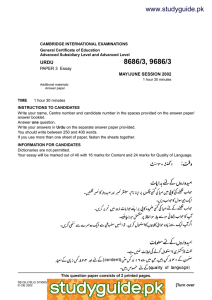

advertisement