Document 12748273

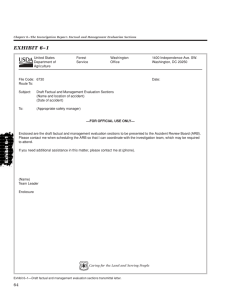

advertisement