Document 12745689

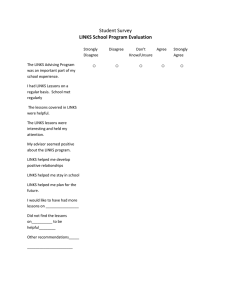

advertisement