E Wood and Environmental Product Declarations

advertisement

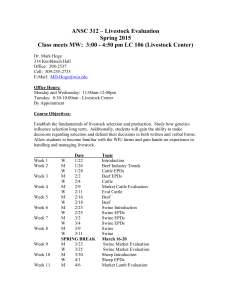

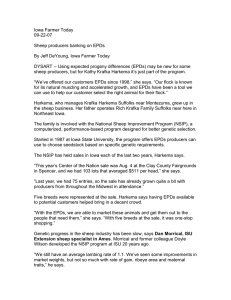

Continuing Education Wood and Environmental Product Declarations New EPDs are part of a growing trend Sponsored by reThink Wood, American Wood Council, and Canadian Wood Council | By Layne Evans E nvironmental Product Declarations (EPDs) are concise, standardized, independently verified reports on environmental performance. Despite their name, they are used not only for products, but also materials and services at either a brand-specific or generic level. There are EPDs in every sector, from automobiles to consumer electronics. This continuing education course focuses on building products, specifically wood products. As this course explains, an EPD gives a decision maker an immediate, reliable, and non-judgmental way to evaluate a product’s environmental impacts over its life cycle—in terms of its embodied energy and global warming potential, and by other important measures such as use of natural resources, emissions to air, soil, and CONTINUING EDUCATION EARN ONE AIA/CES HSW learning unit (lu) EARN ONE GBCI CE hour For Leed credential Maintenance Learning Objectives After reading this article, you should be able to: 1. Describe the function and format of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), and how they are used to analyze a building product’s environmental impact throughout its life cycle. 2. D ifferentiate EPDs from other types of ecolabels, rating systems, and certifications of environmental performance. 3. E xplain how EPDs are being used now, and the factors driving more product manufacturers to develop them and more designers and specifiers to use them as a standard part of sustainable product selection. 4. Evaluate the information in an EPD, using recently published EPDs on wood products. To receive credit, you are required to read the entire article and pass the test. Go to ce.greensourcemag.com for complete text and to take the test for free. AIA/CES COURSE #K1307D GBCI COURSE #0090010009 1 Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Photo by Peter Powles comprehensive, transparent data about environmental impacts. This course will explain why EPDs are important, and how to understand and use the information in an EPD, with particular reference to EPDs recently released for lumber and glued laminated timber (glulam). The wood industry in the U.S. and Canada has been at the forefront of the trend, undertaking research and developing life cycle information that verify the environmental impact of wood building products. As the tools for analyzing and substantiating environmental performance become more sophisticated, the wood industry is working to use them to help the building community better understand wood as a building material in the context of its environmental impact. Photo by KK Law EPD Explained By definition, an EPD for a commodity product like lumber can only review the life cycle from cradle-to-gate. See the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) section below. water, and waste generation. The relevant characteristics and units of measurement for a given product are determined through an open, independent process, so that products in the same category can be compared directly in a much more transparent and meaningful way than is otherwise possible. Although EPDs have become a standard part of decision making elsewhere in the world (see sidebar “Global EPDs”), they are relatively new to North America— produced mainly by large manufacturers or industries committed to being leaders in environmental performance, and used by leading design firms with the same objective. But the use of EPDs in the building industry is currently expanding, thanks to a growing demand for sustainability in every aspect of a building’s design, construction, and operation, and the recognition that this cannot be effectively accomplished without verifiable, Putting labels in Perspective Graphic courtesy of Wayne Trusty 2 EPDs are a means of presenting environmental information in a standardized way, independently verified by a third party. They conform to standards by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) with global applicability. The specific elements of an EPD are discussed in detail later in the course, but following are some key concepts and terminology: Environmental Labels, Ecolabels, EPDs EPDs are just one part of a large universe of environmental labels or “ecolabels.” ISO defines three general categories of ecolabels: Type I labels (ISO 14024) are awarded by third-party programs to products that have good environmental attributes, usually according to a single attribute. An example would be an energy-efficient product identified with the well-known Energy Star logo. Type II labels (ISO 14021) represent selfdeclared claims by product manufacturers about some aspect of their product. An example would be a product identified as containing recycled content or being biodegradable, acknowledged with a logo developed by the manufacturer for the purpose of identifying its corporate sustainability efforts. Type III environmental declarations or EPDs contain quantified environmental data based on life cycle assessment (see definition below), presented in a standardized format in accordance with ISO 14025 and 21930, and independently verified. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Data reported in an EPD is collected using life cycle assessment methodology. LCA is a scientific, internationally accepted technique for assessing environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life. LCAs involve compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases, and evaluating their potential impacts— which helps people make informed decisions about the products they use. Analyzed metrics typically include (among others) global warming potential, acidification and smog potential, resource consumption, and waste generation. Although LCA doesn’t address every potential issue, it has emerged as the most comprehensive and credible way to compare products and make decisions based on key environmental impacts. Business-to-business EPDs, including the ones featured in this course, look at the life cycle from cradle-to-gate: from the extraction of raw materials to the factory “gate” or the point at which the product or material has been manufactured and Wood and Environmental Product Declarations is ready for shipment. By definition, an EPD for a commodity product like lumber can only be cradle-to-gate because the manufacturer may not be able to characterize how the product is used after it is sold. This is in contrast to business-to-consumer EPDs that analyze the life cycle from cradle-to-grave, taking into account the entire service life of the product including its eventual disposal or recycling. Embodied Impacts A product EPD reports “embodied” environmental impacts—for example, on energy resources, air quality, fresh water, or the atmosphere. A product’s embodied impacts include those from its raw material, its manufacturing and transportation, and many other related processes. Depending on the type of EPD, a product’s embodied impacts might be reported from cradle-togate, or might extend to those that occur during installation, maintenance, and disposal or recycling. Embodied energy is the measure of the energy consumed at various stages of the life cycle. Depending on the structural and finishing materials used, each of the many products in a building may require large amounts of carbon-intensive fossil fuel energy to extract or produce the raw materials, transport them to the processing site, manufacture them, transport them to the construction site, and then to install, use, and maintain them, and finally to dispose or recycle them at the end of their service lives. This energy embodied in buildings has typically received less attention than the energy used to operate buildings. But as we create higher-performance, more energy-efficient Product Category Rules (PCR) Though governed by international protocols that guide how they are conducted, LCAs of different products may use different boundaries (i.e., may or may not include certain steps in raw material procurement, product use, or end of life disposal), making comparison of results difficult. ISO has addressed this problem by requiring EPDs to be based on a set of Product Category Rules that specify the parameters to be considered for a given family of products. These PCRs are developed by the Program Operator (see below) for the purpose of ensuring consistency and comparability of EPDs across a category of “products” that serve equivalent functions. For example, a Product Category could be as broad as all construction products or as narrow as 3 Continuing Education An EPD is a declaration of the results of life cycle assessment (LCA). It is a fact-based document including a summary of LCA, product description such as performance features and raw material content, as well as an overview of the manufacturing process. buildings, they use much less operating energy. So their embodied energy takes on greater significance, since it becomes a higher proportion of the building’s total life cycle energy use. Operating energy typically depends less on the choice of structural material, and more on factors such as air tightness, insulation, lighting, and occupant behavior. Embodied energy, on the other hand, is closely connected to the choice of structural material, so it is important to look at both the operating and embodied energy when evaluating a building design in terms of energy consumption. Another reason why embodied energy is an increasingly important consideration is that reductions in the embodied carbon emissions of materials have an immediate benefit, while the carbon benefits of reducing the building’s energy consumption in operations are accrued over a longer period of time. For example, during the first 20 years of occupancy, at least 45 percent of a building’s total energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are from the energy embodied in the building’s materials and construction (Architecture 2030 Challenge for Products). Many experts point out that the next 20 years are expected to be a crucial time in the struggle against climate change. Reducing the embodied carbon emissions of materials has an important role to play in slowing global climate change by lowering the amount of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere and doing it as quickly as possible. To that end, targeted information that enables comparison of building products based on their embodied energy and other impacts is a pressing need. Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Photo by Gord Wylie Due to performance and energy efficiency gains, buildings are using much less operating energy. This places a greater significance on embodied energy since it becomes a higher proportion of the building’s total life cycle energy use. gypsum wallboard. A Product Category could be material-based (such as wood products) or component-based (such as wall framing). The creation of PCRs is a rigorous process guided by ISO standards and, in some cases, other regional standards or protocols. Program Operator A body that conducts a Type III Environmental Declaration Program is called the Program Operator, and can be a company, a group of companies, an industrial sector or trade association, public authority or agency, or independent scientific body or other organization (ISO 14025). Program Operators develop and publish PCRs. side-by-side comparison across multiple criteria (for example, sodium, calories, saturated fat, etc.). Building product EPDs make environmental information available in the same neutral, transparent manner. But building materials and products are much more complex than a cereal or frozen food product, and much more dependent on how the product is actually used. At the same time, building products even in the same category do differ radically in their environmental impact. EPDs capture these EPDs in the Building Industry In this course, the focus is on EPDs created by building product manufacturers or industry groups, to be used by architects, engineers, specifiers, and builders to evaluate and compare LCA information on building products. EPDs are often compared to nutrition labels on food products, and the comparison for building products is valid in some ways. The information is neutral, and presented in a standardized format so that one product can be compared to another. A food nutrition label does not state whether a food is good or bad, or deserves a “Good Food Badge.” It merely states the nutritional properties of the food and enables a fair 4 Developing an EPD: steps and participants impacts by establishing clear categories, and defining scope and boundaries for the LCA information. As more PCRs and EPDs are developed, direct side-by-side comparisons are becoming easier for products serving similar functional roles under the same PCR. But even now, it is possible to use the results reported in EPDs to make more informed product selection decisions. As mentioned earlier, EPDs can be created for all types of products and services—from building materials to equipment, flooring, and other finishing elements. The PCR is established and the LCA data gathered and communicated in the EPD. When properly structured and verified against the same PCR, the EPD for one alternative can be compared against the EPD for another. The key is that the functional unit must be the same for relevant comparison. Products are components of buildings and therefore must be considered within a system at the building level, providing the same functionality, in accordance with the specific criteria in the ISO standards. EPDs are constituted in accordance with sets of standard PCRs to ensure that EPDs of products produced by different organizations in the same functional use category use the same scope of data and metrics. This supports consistency within an industry and enables comparison of products via the use of EPDs. The PCR process and the use of ISO 14040 peer-reviewed LCAs make EPDs the most accurate form of environmental declaration available. Many new PCRs are being created in the building industry. The number of full- Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Photo by Gord Wylie Continuing Education Global EPDs EPDs are currently being developed worldwide, through various mechanisms. Many are developed by independent organizations, while others are developed within highly organized frameworks. EPDs have momentum in Europe and Asia, while North America is taking its initial steps. A key to EPD development is the creation of a national infrastructure, including standards and Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) databases. fledged, published EPDs is also growing. Current building industry EPDs include ceiling tiles, office chairs, carpet, lighting systems, concrete, and many others. The North American wood industry has completed and published several EPDs to date, including: softwood lumber, glulam, western red cedar decking and siding, softwood plywood, and oriented strand board (OSB). EPDs simplify comparison for information users. They are specifically designed to be brief documents, and to convey relatively complex LCA information in a simple, concise way. But producing EPDs is no simple matter for the product manufacturer. Only manufacturers prepared to produce extensive LCA information for their products, to submit it to independent third-party scrutiny, and to divulge information that many companies might consider highly confidential, have so far created EPDs. But they are doing so because the advantages of providing information in the EPD format in the building industry are growing. Why EPDs Now? On one hand, the proliferation of ecolabels is a positive sign, indicating the desire of both consumers and businesses to make sustainable choices. But it can also be confusing and counterproductive for decision makers all along the chain. So much information is available now about products that at first glance it might be difficult to understand why we need yet another ecolabel. There are currently more than 500 ecolabels worldwide, with about 100 in the U.S. alone. Many have proved extremely valuable for raising both awareness and performance in a wide range of products. But as sophistication in design and product manufacturing has increased, along with awareness and demand from clients and the public, it becomes obvious that the information available is not as transparent and useful as it could be. Some are outright greenwashing. Some are based on a manufacturer’s claims, policies, or intentions, and although these are often true indicators of environmental consciousness, they are focused on the particular market needs of the company. Even some excellent programs are limited in certain ways. They may focus only on a “single attribute” such as energy use or low volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or they may award seals that require knowledge of the program’s aims and procedures to evaluate. A 2011 study by BuildingGreen, an independent sustainable design information source, highlighted the importance of backing up claims with third-party verification and providing clear documentation of green characteristics. The study found growing distrust of product information, frustration about lack of transparency, and confusion about the overwhelming number of standards and labels. Ecolabels have traditionally been aimed at consumers, but they are also becoming Europe A number of European countries have all components of an EPD infrastructure in place, especially Sweden, Italy, France, Germany, and the UK (CME 2010). Sweden was the earliest, and led the creation of the international EPD network. The EU is working to ensure compatibility among databases and harmonization of EPD programs. France has developed an EPD-based national strategy for increasing the importance of environmental data in consumer choices and product manufacturing, and is the first EU nation to move towards mandatory EPDs. Asia and Pacific Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, and Australia have some or all of an EPD infrastructure in place. Japan has spent significant federal dollars on a national database and the advancement of its EPD program, EcoLeaf. important in business-to-business and business-to-government purchasing decisions. Clearly, science-based, thirdparty-reviewed information is required. EPDs fulfill this function, making evaluation of environmental impacts of products accurate and transparent. They also give a better picture of overall environmental impact. A product may have recycled content, for example, yet require so much fossil fuel to transport that any benefit is outweighed. EPDs can also lead to reduced environmental impacts. When a product undergoes the life cycle assessment necessary to create an EPD, the manufacturer main gain valuable insight into “hot spots”—i.e., points at which 5 Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Impact Assessment Categories Impact Category Indicators Characterization Model Global Warming Potential Calculates global warming potential of all greenhouse gasses that are recognized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The characterization model scales substances that include methane and nitrous oxide to the common unit of kg CO2 equivalents. Ozone Depletion Potential Calculates potential impact of all substances that contribute to stratospheric ozone depletion. The characterization model scales substances that include chlorofluorocarbon, hydrochlorofluorocarbon, chlorine, and bromine to the common unit of kg CFC-11 equivalents. Potential Calculates potential impacts of all substances that contribute scales substances that include sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and ammonia to the common unit of H+ moles equivalents. Smog Potential Calculates potential impacts of all substances that contribute to photochemical smog potential. The characterization model scales substances that include nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds to the common unit of kg O3 equivalents. Eutrophication Potential Calculates potential impacts of all substances that contribute to eutrophication potential. The characterization model scales substances that include nitrates and phosphates to the common unit of kg N equivalents. Impact Category Indicators Table from the Softwood Lumber EPD: The life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) results are calculated for impact category indicators such as global warming potential and smog potential. These results provide general, but quantifiable, indications of potential environmental impacts. The various indicators and means of characterizing the impacts are summarized in this table. processes could be made more efficient and more environmentally benign. EPDs are expressions of commitment to long-term sustainability and positive environmental stewardship. The information contained in EPDs is quantifiable and verifiable—but it is not the final word, by any means. EPDs are complementary to other third-party independent certifications such Energy Star labels and forest certification programs (for example, Forest Stewardship Council, Sustainable Forestry Initiative, and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification). EPDs remain only one of many reporting mechanisms, and product certification continues to serve important functions. Products have other impacts besides those covered by EPDs, involving human and social values such as fair practices, biodiversity, and many others. In the case of wood products, for instance, sustainably managing forests with future generations in mind, conserving biodiversity, and protecting other values related to forests have great worth and complement the parameters measured in an EPD. Together, EPDs and forest certification provide a more complete picture of the environmental attributes of a forest product. Putting EPDs to Work Environmentally conscious architects, engineers, and specifiers often do their own extensive research related to the 6 environmental attributes of products and materials they select. Even the most committed professionals cannot effectively lower carbon emissions and other negative impacts of building design and construction unless they have a true understanding of what those impacts are. EPDs are an important additional tool. In other parts of the world, EPDs and other environmental labels play a key role on a national level (see sidebar “Global EPDs”). In the U.S., there are currently a number of initiatives in both the public and private sectors. Codes are driving demand for verified LCA information on products, notable examples of which include the California Green Building Code (CALGreen), the International Green Construction Code (IgCC) for commercial buildings, and the International Code Council’s ICC 700—the National Green Building Standard aimed at residential and multifamily construction. Two initiatives in the private sector are also driving both the development and use of EPDs: 2030 Challenge for Products: Architecture 2030 issued the “2030 Challenge” program calling for changes in building design and construction to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2030. The 2030 Challenge for Products aims to reduce the embodied carbon in building products by 50 percent over the same time period. The plan calls for participating manufacturers to develop accurate and comparative data on the embodied carbon of their products. Industry groups are developing PCRs and ultimately EPDs to standardize data across product categories and to track progress toward the embodied energy goals. More information is available at the 2030 Challenge Information Hub, a joint effort of BuildingGreen, Architecture 2030 and the Healthy Building Network (see the list of resources at the end of this CEU). USGBC LEED: Among the new credits proposed for the Material & Resources section of the upcoming U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) v4 rating system is Building Product Disclosure and Optimization – Environmental Product Declarations. The credit would reward project teams at various levels for selecting products that have EPDs. Meanwhile, LEED Pilot Credit 52 Material Multi-Attribute Assessment gives architects the opportunity to gain points immediately by using EPDs (required for at least 20 products) to document performance. For example, Option 1. Environmental Product Declaration outlines the increasing point contribution available for three types of EPDs: Product-specific life cycle assessment (valued at ¼ product) I ndustry-wide generic third-party certified Type III EPDs (valued at ½ product) For the highest contribution, productspecific third-party certified Type III EPDs (valued at 1 product) Photo by Craig Carmichael The North America wood industry has produced EPDs for softwood lumber, glue laminated timber, softwood plywood, oriented strand board, and western red cedar decking and siding. Cradle-to-gate product system for kiln-dried, CRADLE-TO-GATE PRODUCT SYSTEM planed softwood lumber FOR KILN-DRIED, PLANED SOFTWOOD LUMBER Anatomy of an EPD Program Operator Certification While EPDs are owned by the manufacturer (“declaration holder”), they are verified by a third-party, independent Program Operator, as discussed above. Program Operators develop and own the PCRs. For the wood EPDs discussed here, the Program Operators are UL Environment and FPInnovations, two of a small number of Program Operators currently issuing EPDs in the U.S. and Canada. The Program Operator’s responsibilities are set out in the standards, and involve setting product category rules, reviewing and verifying EPDs, and in general ensuring that the steps laid out in the standards are followed. One of the most important responsibilities of the Program Operator is the development of the Product Category Rules. The product category will describe the scope and methodology of the LCA information, including the attributes of the range of products covered, and the ways they will be measured and described. These rules make it possible for information Forest Management thinning, fertilization Electricity Energy gasoline, diesel Ancillary Materials lubricants, fertilizers Logging felling, transport to landing Planting including site preperation Roundwood logs on truck Transportation Electricity Log Yard manufacturing facility Energy diesel, wood, fuel liquefied petroleum gas, natural gas Sawmill debarking and primary log breakdown Kiln-Drying Product Manufacturing Governing Standards The standard governing Type III EPDs is ISO 14025. For building products, ISO 21930 specifically addresses PCR and EPD standards for the building construction sector. The first pages of the EPD typically introduce the sponsoring organization or company, cite the standards, and summarize the information included, such as the specific LCA results covered in the report. Seedling greenhouse operations Resource Generation & Extraction In this section we’ll use new third-party certified EPDs recently released for generic forest products as examples to explain the major standardized elements of an EPD and the information they contain. The North American forest products industry is producing generic industry EPDs for structural and non-structural wood products. The reports discussed in this course are on softwood lumber and glulam. Distinct from these generic third-party certified EPDs would be a product-specific third-party certified EPD, which would reflect the parameters for an individual company’s manufacturing facility. Although different organizations can choose to present the reports in their own formats, some major elements will appear in every EPD: Continuing Education For more information about the pilot credit, see the list of resources at the end of this course. Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Cradle-to-gate life cycle of softwood lumber EPD illustrating the inputs and outputs through the various stages of the life cycle: The lumber EPD includes LCA results for all processes up to the point that planed and dry lumber is packaged and ready for shipment at the manufacturing gate; the cradle-to-gate product system includes forest management, logging, transportation of logs to lumber mills, sawing, kiln-drying, and planing. The delivery of the product to the customer, its use, and eventual end-of-life processing are excluded from the cradle-togate portion of the life cycle. This exclusion means the carbon stored in the wood itself is not accounted for since the benefit of sequestration is not realized at the point of manufacturing, but occurs over the life cycle of the product. Planing Softwood Lumber dried, planed System Boundary about products in the same category to be effectively compared. Description of Industry and Product: In the wood product examples, this section describes the North American forest products industry and includes a detailed description of the specific lumber product, its manufacturing processes, units of measure, dimensions, and components (e.g., wood and glue in the case of glulam). Scope of LCA In general, LCA information in EPDs will either be cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave. As with many business-to-business EPDs, the ones used in this course as examples focus on cradle-to-gate: the life cycle up to the point that the product has been manufactured and is ready for shipment. Cradle-to-gate excludes data about delivery of the product, its use and its end-of-life processing. The end user of the product can take the cradle-to-gate EPD information and add the rest of the story to complete the cradle-to-grave picture. Methodology of the Underlying LCA This section documents the methodology of the underlying LCA used, including assumptions such as the declared unit, system boundaries, data quality, aggregation of regional results, and other indicators such as how biogenic carbon is addressed. LCA Results The heart of the EPD is the LCA results. The Impact Assessment Categories are determined by the ISO and EU standards and specified in the PCR. In these examples, indicators include global warming 7 Wood and Environmental Product Declarations Lumber EPD—Snapshot of Certification Program operator UL Environment Declaration holder American Wood Council and Canadian Wood Council Declaration number 11CA41590.102.1 Declared product North American Softwood Lumber Reference PCR FPInnovations: 2011. Product Category Rules (PCR) for preparing an Environmental Product Declaration for North American Structural and Architectural Wood Products, Version 1 (UN CPC 31, NAICS 321), November 8, 2011 Date of issue April 16, 2013 Period of validity 5 years measure of the environmental attributes of a product. Other third-party certifications such as forest certification are essential and complementary, and provide additional information about environmental performance. When EPDs are read in conjunction with other certifications, they represent the most complete picture yet of a product’s environmental performance. As such, they are helping to usher in a new era of disclosure and transparency. Additional Resources For information on development and use of PCRs and EPDs, consult the following: Product information and building physics Information about basic material and the material’s origin Content of the declaration Description of the product’s manufacture Indication of product processing Information about the in-use conditions Life cycle assessment results Testing results and verifications The Declaration page of the North American Softwood Lumber EPD specifies such things as the Program Operator, owner of the EPD, the reference PCR, and the independent verifier. potential, ozone depletion potential, acidification potential, smog potential and eutrophication (excess nutrients that promote harmful plant growth in water bodies) potential. In addition to these indicators, the LCA results present total primary energy consumption and material resources consumption, including fresh water. Summary An EPD includes information about both product attributes and production impacts, and provides consistent and comparable information to industrial customers and end-use consumers regarding environmental performance. The nature of EPDs also allows summation of environmental impacts along a product’s entire supply chain—a powerful feature that greatly enhances the utility of LCAbased information. To begin taking advantage of the usefulness of EPDs, and to encourage their widespread development, designers can use the LEED Pilot Credit, and discuss EPDs with product manufacturers, asking whenever possible for verified LCA information compliant with international standards. Designers, organizations, and manufacturers can commit to the Architecture 2030 Challenge, and participate in the rapid developments on this front. As more EPDs are developed, the amount of information expands and, in time, a virtuous circle commences. Better ability to evaluate and compare leads to more rigorous purchasing and specifying, which in turn leads to better products manufactured by companies increasingly eager to document and present the evidence of their superior environmental performance. EPDs are not necessarily the “be all and end all” American Wood Council and Canadian Wood Council EPDs (http://www.awc.org/ greenbuilding/epd.html) for Wood Products UL Environment (http://www.ul.com/ global/eng/pages/offerings/businesses/ environment/services/certification/epd/) Western Red Cedar Lumber Association EPDs for Cedar Products (http://www. wrcla.org/cedar_benefits/environment/ benefits_of_wood/default.htm) FPInnovations (http://www.fpinnovations. ca/files/html/en/fpsolutions/PB_edp_ en.html) Architecture 2030 Challenge (http:// architecture2030.org/) BuildingGreen 2030 Challenge for Products Information Hub (http://www2. buildinggreen.com/topic/2030-challenge) USGBC LEED Pilot Credit 52 (http:// www.usgbc.org/node/2606888?return=/ pilotcredits) The reThink Wood initiative is a coalition of interests representing North America’s wood products industry and related stakeholders. The coalition shares a passion for wood and the forests it comes from. Innovative new technologies and building systems have enabled longer wood spans, taller walls, and higher buildings, and continue to expand the possibilities for wood use in construction. www.rethinkwood.com American Wood Council is the leading developer of engineering data, technology, and standards on structural wood products in the U.S. These tools are used widely by design professionals, building officials, and manufacturers of traditional and engineered wood products to ensure the safe and efficient design and use of wood structural components. www.awc.org The Canadian Wood Council is the national association representing manufacturers of Canadian wood products used in construction. Through its member associations, the Council represents those manufacturers. www.cwc.ca 8 Canadian Wood Council Reprinted from the July/August 2013 issue of GreenSource Conseil canadien du bois