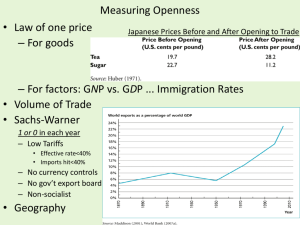

“Globalisation, Convergence and the Case for Openness

advertisement