Babylon University ... Colleague of Medicine ...

advertisement

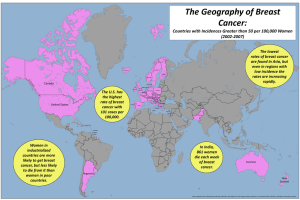

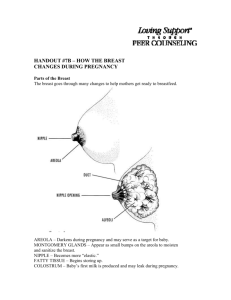

Babylon University Colleague of Medicine Dr.Ahmed Raji Fourth Stage Lecture 2 Breast Pathology Benign Epithelial Lesions The benign epithelial lesions of the breast have been divided into three groups, according to the risk of developing breast cancer: (1) Nonproliferative breast changes. (2) Proliferative breast disease. (3) Atypical hyperplasia. Nonproliferative Breast Changes (Fibrocystic Changes) This group includes a number of morphologic changes which includes: cystic changes, fibrosis, adenosis, which are often grouped under the term fibrocystic changes. These lesions are termed nonproliferative to distinguish them from “proliferative” changes, which are associated with a more increased risk of breast cancer. These changes usually present as ill-defined mass. Morphology. (1) Cystic change: Small cysts form by the dilation of lobules, and it may coalesce to form larger cysts. Cysts are lined either by a flattened atrophic epithelium or by metaplastic apocrine cells, and contain turbid, semi-translucent fluid, the diagnosis is confirmed by the disappearance of the cyst after fine-needle aspiration of its contents. (2) Fibrosis: Cysts frequently rupture, releasing secretory material into the adjacent stroma. The resulting chronic inflammation and fibrosis contribute to the palpable firmness of the breast. (3) Adenosis (blunt duct adenosis): Adenosis is defined as an increase in the number of acini per lobule. A normal physiologic adenosis occurs during pregnancy, the acini are often enlarged but are not distorted. Proliferative Breast Disease without Atypia These are group of changes that are commonly detected as 1 - Mammographic densities 2 - Mammographic calcifications 3 - Incidental findings in specimens from biopsies performed for other reasons. 4 - As nipple discharge: more than 80% of large duct papillomas produce a nipple discharge 5 - As small palpable masses. Although each lesion can be found in isolation, typically more than one lesion is present together. These lesions are characterized by proliferation of ductal epithelium and/or stroma without cytologic or architectural features suggestive of carcinoma. These changes includes: moderate or florid epithelial hyperplasia, sclerosing adenosis, papilloma, complex sclerosing lesion (radial scar) and fibroadenoma. Epithelial Hyperplasia: Normal breast ducts and lobules are lined by a double layer of myoepithelial cells and luminal cells, epithelial hyperplasia is defined by the presence of more than two cell layers. Papillomas: Papillomas are composed of multiple branching fibrovascular cores, each having a connective tissue axis lined by luminal and myoepithelial cells, growth occurs within a dilated duct. Fibroadenoma: This is the most common benign tumor of the female breast, most occur in women in their 20s and 30s, and they are frequently multiple and bilateral. The epithelium of the fibroadenoma is hormonally responsive, and an increase in size due to lactational changes during pregnancy, which may be complicated by infarction and inflammation, can mimic carcinoma. The stroma often becomes densely hyalinized after menopause and may calcify. Fibroadenomas were originally grouped with other “proliferative changes without atypia” in conferring a mild increase in the risk of subsequent cancer. However, in one study the increased risk was limited to fibroadenomas associated with cysts larger than 0.3 cm, sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcifications, or papillary apocrine change (“complex fibroadenomas”) Morphology of fibroadenoma: Grossly freely movable, well-circumscribed, rubbery, grayish white nodules that vary in size from less than 1 cm to large tumors that can replace most of the breast and often contain slitlike spaces. Microscopically Delicate, cellular, and often myxoid stroma resembles normal intralobular stroma. The epithelium may be surrounded by stroma or compressed and distorted by it, in older women, the stroma typically becomes densely hyalinized and the epithelium atrophic. Proliferative Breast Disease with Atypia Proliferative disease with atypia includes 1 - Atypical ductal hyperplasia and 2 - Atypical lobular hyperplasia. Atypical ductal hyperplasia is present in 5% to 17% of specimens from biopsies performed for calcifications and is found less frequently in specimens from biopsies for mammographic densities or palpable masses. Atypical lobular hyperplasia is an incidental finding and is found in fewer than 5% of specimens from biopsies performed for any reason. Morphology. Atypical ductal hyperplasia consists of a relatively monomorphic proliferation of regularly spaced cells, sometimes with cribriform spaces. It is distinguished from DCIS by being limited in extent and only partially filling ducts. Atypical lobular hyperplasia consist of a proliferation of cells identical to those of lobular carcinoma in situ, but the cells do not fill or distend more than 50% of the acini within a lobule. Clinical Significance of Benign Epithelial Changes Multiple epidemiologic studies have classified the benign changes in the breast and determined their association with the later development of invasive cancer. Nonproliferative changes do not increase the risk of cancer. Proliferative disease is associated with a mild increase in risk. Proliferative disease with atypia confers a moderate increase in risk. Both breasts are at increased risk. Risk reduction can be achieved by bilateral prophylactic mastectomy or treatment with estrogen antagonists, such as tamoxifen. However, more than 80% of women with atypical hyperplasia will not develop breast cancer, and many choose careful clinical and radiologic surveillance over intervention. TABLE -Epithelial Breast Lesions and the Risk of Developing Invasive Carcinoma. Pathologic Lesion NONPROLIFERATIVE changes) Relative Risk BREAST CHANGES (Fibrocystic 1.0 Duct ectasia Cysts Apocrine change Mild hyperplasia Adenosis PROLIFERATIVE DISEASE WITHOUT ATYPIA 1.5 to 2.0 Moderate or florid hyperplasia Sclerosing adenosis Papilloma Complex sclerosing lesion (radial scar) Fibroadenoma with complex features PROLIFERATIVE DISEASE WITH ATYPIA 4.0 to 5.0 Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) CARCINOMA IN SITU Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) 8.0 to 10.0 Carcinoma of the Breast Carcinoma of the breast is the most common malignancy in women. A woman who lives to age 90 has a one in eight chance of developing breast cancer. In 2007 an estimated 178,480 women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, 62,030 with carcinoma in situ, and over 40,000 women died of the disease. Only lung cancer causes more cancer deaths in women living in the United States. Risk factors Age The incidence rises throughout a woman's lifetime, peaking at the age of 75–80 years and then declining slightly thereafter. Age at Menarche Women who reach menarche when younger than 11 years of age have a 20% increased risk compared with women who are more than 14 years of age at menarche. Late menopause also increases risk. Age at First Live Birth Women who experience a first full-term pregnancy at ages younger than 20 years have half the risk of nulliparous women or women over the age of 35 at their first birth. First-Degree Relatives with Breast Cancer The risk of breast cancer increases with the number of affected first-degree relatives (mother, sister, or daughter), especially if the cancer occurred at a young age. Atypical Hyperplasia A history of prior breast biopsies, especially if revealing atypical hyperplasia, increases the risk of invasive carcinoma. There is a smaller increase in risk associated with proliferative breast changes without atypia. Race/Ethnicity Non-Hispanic white women have the highest rates of breast cancer. The risk of developing an invasive carcinoma within the next 20 years at age 50 is 1 in 15 for this group, 1 in 20 for African Americans, 1 in 26 for Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 1 in 27 for Hispanics, social factors such as decreased access to health care and lower use of mammography may well contribute to these disparities, but biologic differences also play an important role. Estrogen Exposure Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy increases the risk of breast cancer 1.2to 1.7-fold, and adding progesterone increases the risk further. Oral contraceptives have not been shown convincingly to affect breast cancer risk but do decrease the risk of endometrial and ovarian carcinomas. Reducing endogenous estrogens by oophorectomy decreases the risk of developing breast cancer by up to 75%. Drugs that block estrogenic effects (e.g., tamoxifen) or block the formation of estrogen (e.g., aromatase inhibitors) also decrease the risk of breast cancer. Breast Density High breast radiodensity is a strong risk factor for developing cancer. High density is correlated with young age and hormone exposure, and clusters in families. High breast density may be related to less complete involution of lobules at the end of each menstrual cycle, which in turn may increase the number of cells that are potentially susceptible to neoplastic transformation. Radiation Exposure Radiation to the chest, whether due to cancer therapy, atomic bomb exposure, or nuclear accidents, results in a higher rate of breast cancer. The risk is greatest with exposure at young ages and with high radiation doses. Carcinoma of the Contralateral Breast or Endometrium Approximately 1% of women with breast cancer develop a second contralateral breast carcinoma per year. Geographic Influence Breast cancer incidence rates in the United States and Europe are four to seven times higher than those in other countries. The risk of breast cancer increases in immigrants to the United States with each generation. The factors responsible for this increase are of considerable interest because they are likely to include modifiable risk factors. Reproductive history (number and timing of pregnancies), breastfeeding, diet, obesity, physical activity, and environmental factors all probably play a role. Diet Large studies have failed to find strong correlations between breast cancer risk and dietary intake of any specific type of food. Coffee addicts will be pleased to know that caffeine consumption may decrease the risk of breast cancer. On the other hand, moderate or heavy alcohol consumption increases risk. Obesity There is decreased risk in obese women younger than 40 years as a result of the association with anovulatory cycles and lower progesterone levels late in the cycle. In contrast, the risk is increased for postmenopausal obese women, which is attributed to the synthesis of estrogens in fat depots. Exercise There is a probable small protective effect for women who are physically active. The decrease in risk is greatest for premenopausal women, women who are not obese, and women who have had full-term pregnancies. Breastfeeding The longer women breastfeed, the greater the reduction in risk, lactation suppresses ovulation and may trigger terminal differentiation of luminal cells, the lower incidence of breast cancer in developing countries largely can be explained by the more frequent and longer nursing of infants. Environmental Toxins There is concern that environmental contaminants, such as pesticides, have estrogenic effects on humans. Possible links to breast cancer risk are being investigated intensively, but definitive associations have yet to be made. Tobacco Cigarette smoking has not been clearly associated with breast cancer but is associated with the development of periductal mastitis.