Ballet, Birmingham and Me Sheila Galloway and Jonothan Neelands

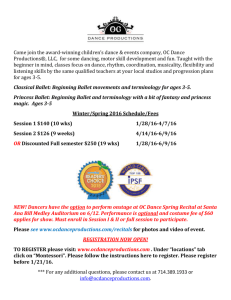

advertisement