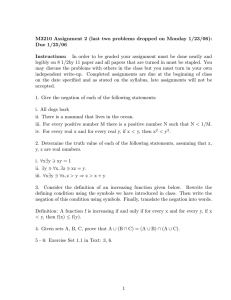

Force, negation and imperatives

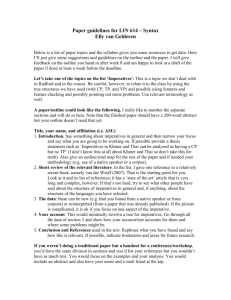

advertisement