M V THE PICO-FICINO CONTROVERSY: NEW EVIDENCE IN FICINO’S COMMENTARY

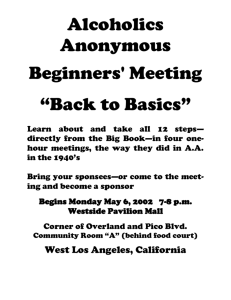

advertisement