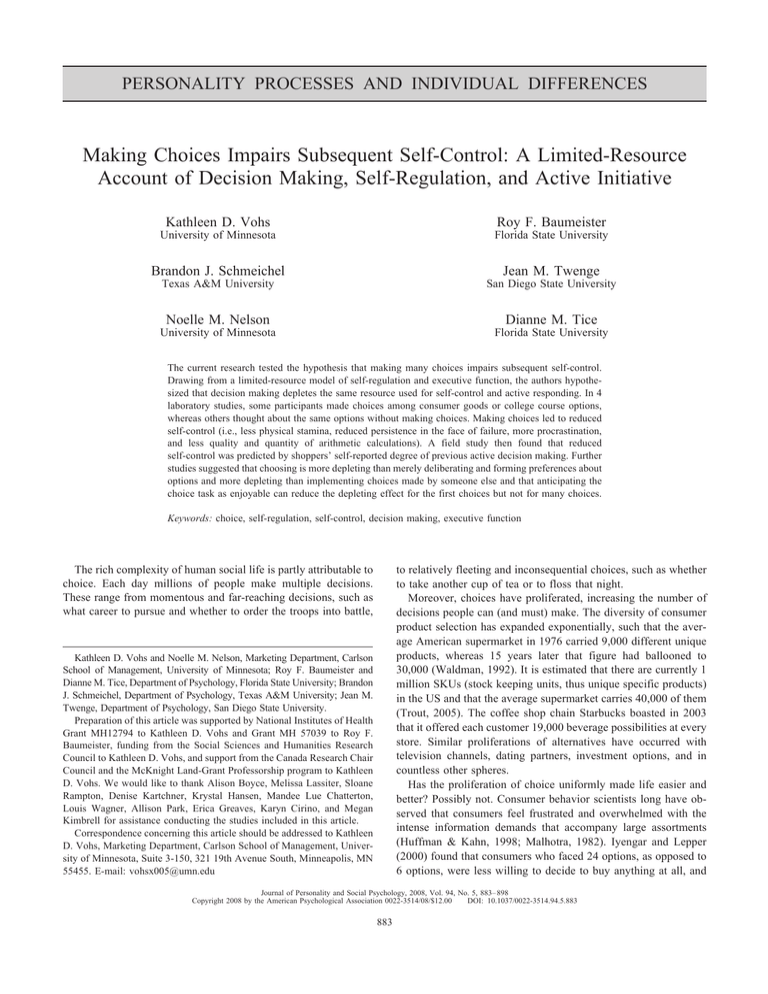

Making Choices Impairs Subsequent Self-Control: A Limited-Resource

advertisement