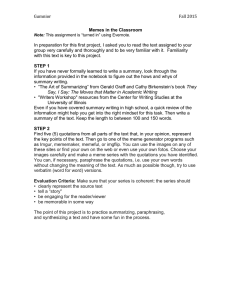

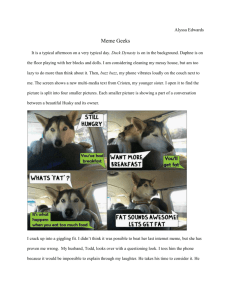

Satirical User-Generated Memes as an Effective Source of Political Enhancing Civic Engagement

advertisement