RESE ARCH P A P E R S

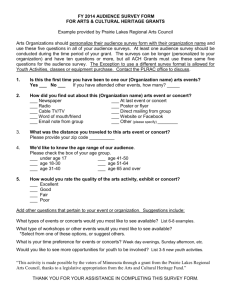

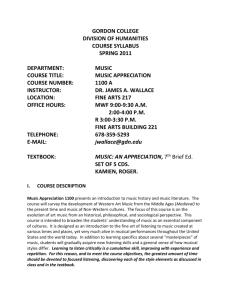

advertisement