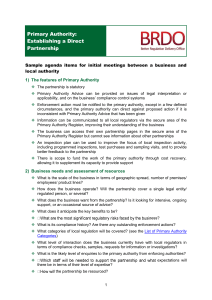

Evaluating the Primary Authority Scheme

advertisement