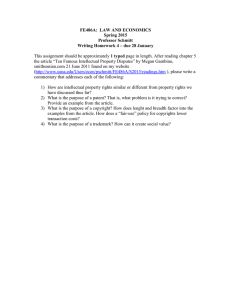

(An Electronic Law Journal) Law, Social Justice & Global Development Culture War

advertisement