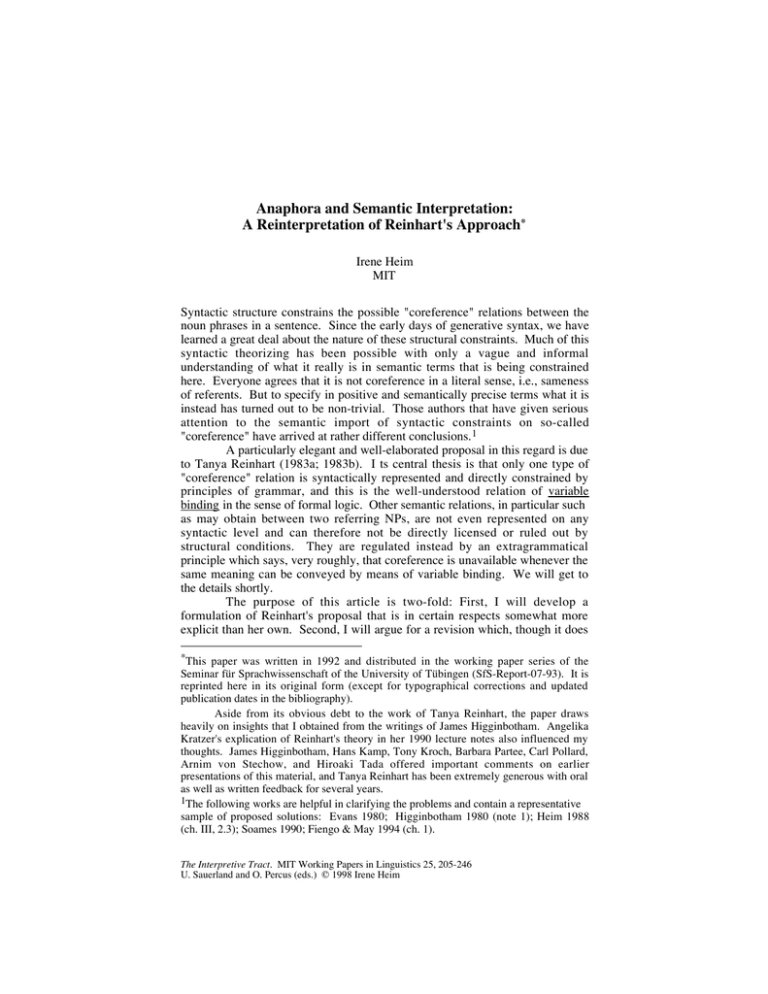

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation: A Reinterpretation of Reinhart's Approach

advertisement

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation:

A Reinterpretation of Reinhart's Approach*

Irene Heim

MIT

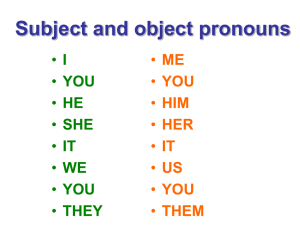

Syntactic structure constrains the possible "coreference" relations between the

noun phrases in a sentence. Since the early days of generative syntax, we have

learned a great deal about the nature of these structural constraints. Much of this

syntactic theorizing has been possible with only a vague and informal

understanding of what it really is in semantic terms that is being constrained

here. Everyone agrees that it is not coreference in a literal sense, i.e., sameness

of referents. But to specify in positive and semantically precise terms what it is

instead has turned out to be non-trivial. Those authors that have given serious

attention to the semantic import of syntactic constraints on so-called

"coreference" have arrived at rather different conclusions. 1

A particularly elegant and well-elaborated proposal in this regard is due

to Tanya Reinhart (1983a; 1983b). I ts central thesis is that only one type of

"coreference" relation is syntactically represented and directly constrained by

principles of grammar, and this is the well-understood relation of variable

binding in the sense of formal logic. Other semantic relations, in particular such

as may obtain between two referring NPs, are not even represented on any

syntactic level and can therefore not be directly licensed or ruled out by

structural conditions. They are regulated instead by an extragrammatical

principle which says, very roughly, that coreference is unavailable whenever the

same meaning can be conveyed by means of variable binding. We will get to

the details shortly.

The purpose of this article is two-fold: First, I will develop a

formulation of Reinhart's proposal that is in certain respects somewhat more

explicit than her own. Second, I will argue for a revision which, though it does

*This paper was written in 1992 and distributed in the working paper series of the

Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft of the University of Tübingen (SfS-Report-07-93). It is

reprinted here in its original form (except for typographical corrections and updated

publication dates in the bibliography).

Aside from its obvious debt to the work of Tanya Reinhart, the paper draws

heavily on insights that I obtained from the writings of James Higginbotham. Angelika

Kratzer's explication of Reinhart's theory in her 1990 lecture notes also influenced my

thoughts. James Higginbotham, Hans Kamp, Tony Kroch, Barbara Partee, Carl Pollard,

Arnim von Stechow, and Hiroaki Tada offered important comments on earlier

presentations of this material, and Tanya Reinhart has been extremely generous with oral

as well as written feedback for several years.

1The following works are helpful in clarifying the problems and contain a representative

sample of proposed solutions: Evans 1980; Higginbotham 1980 (note 1); Heim 1988

(ch. III, 2.3); Soames 1990; Fiengo & May 1994 (ch. 1).

The Interpretive Tract. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 25, 205-246

U. Sauerland and O. Percus (eds.) © 1998 Irene Heim

Irene Heim

leave practically all of Reinhart's substantive insights intact, leads to a theory

which no longer fits the summary I just gave. In particular, the revised theory

implies that bound variable anaphora does not enjoy a special status, but

coreference anaphora is syntactically represented in exactly the same way.

The reader is warned, first, that it is not the purpose of this article to

survey or evaluate the competitors to Reinhart's approach which are already

found in the literature. Aside from some scattered allusions, they will be

disregarded. Of course, if there already is a successful alternative to Reinhart's

approach on the market, then this makes the present enterprise more or less

irrelevant. I do not believe that there is, but it would take a separate paper (or

several) to explain just why not. Second, I will also disregard the numerous

criticisms that other authors have already put forward against Reinhart.2 Some

of them, I believe, have been successfully countered or happen not to apply

against my particular formulation of her ideas. Others remain unrefuted, and

most of those will threaten the revised theory I endorse no less than Reinhart's

original version. For instance, I inherit what are likely to be the wrong

descriptive generalizations about Weak Crossover3 and about ellipsis 4. If I am

lucky, appropriate remedies for these and other shortcomings will not

undermine my main points, but for all I know they might. Apart from these

objections, which I am simply not competent to deal with, I neglect others for

mere reasons of space. In particular, I omit all discussion of Binding Condition

C, even though I defend claims that are not consistent with Reinhart's position

on this matter.5

1. Reinhart's theory

Reinhart's theory of the syntax and semantics of anaphoric relations is best

known from her book Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation (Reinhart 1983a).

My exposition mostly follows the more recent summary in Grodzinsky &

Reinhart 1993 (henceforth G&R). I take the liberty of making some small

technical changes to suit my personal tastes and habits, but these should not

distort any of the substantive ideas.

Let us begin with the central assumptions about the derivation and

well-formedness of S-structure (SS) . We have free, optional indexing . Any NP

may, but need not, be assigned an index (a numerical subscript), and different

2See especially Lasnik 1989 (ch. 9) and references cited there.

3For counterexamples and alternative proposals, see especially Higginbotham 1980 and

Stowell 1987.

4Reinhart and the present work basically follow Sag 1980, which is problematic in light

of a number of more recent studies (see especially Dalrymple, Schieber, Perreira 1991,

Kitagawa 1991, and Fiengo & May 1994.)

5I am persuaded that Condition C is required in the syntax in order to predict the

distribution of bound variable construals for epithets, as shown, e.g., by Haïk 1984

(204f.), Lasnik 1989 (ch. 9), and Higginbotham 1994. This point is independent of the

argument that I have with Reinhart in this article. Once Condition C is reintroduced

alongside A and B, most of what I say about Condition B below will probably carry over

mutatis mutandis to C.

206

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

NPs in a sentence may receive the same or different indices. For instance, we

can assign (1) any of the following indexings (among others 6), though (as we

will see below) some of these lead to derivations that are later filtered out as illformed or uninterpretable.

(1)

Every boy called his mother.

a.

every boy1 called his 1 mother

b.

every boy1 called his 2 mother

c.

every boy called his1 mother

d.

every boy1 called his mother

e.

every boy called his mother

One important filter consists of the Binding Theory conditions A and B, which

apply at SS:

(2)

Binding Conditions:

A.

B.

An anaphor is A-bound in its GC.

A pronominal is not A-bound in its GC.

(2) presupposes a lexical categorization into anaphors (in particular reflexive

pronouns) and pronominals (non-reflexive personal pronouns). It also

presupposes suitable characterizations of "Governing Category" (GC), for which

the reader is referred to the syntactic literature. Moreover, it relies on the

following definitions, which in turn appeal to standard definitions of "Aposition" and "c-command" (most of the time, it will not matter which particular

version).

(3)

a.

α binds β iff α c-commands and is coindexed with β.

b.

α A-binds β iff α binds β and α is in an A-position.

None of (1a-e) happen to be filtered out by the Binding Conditions, but the

reader is surely familiar with examples that would be.

From SS, a transformational derivation leads to Logical Form (LF) .

The main operation of interest in this derivation is so-called Quantifier Raising

(QR) . Contrary to what its name suggests, it applies optionally and freely to all

types of NPs. (But again, derivations in which QR has failed to apply will often

be ruled out by yielding uninterpretable outputs.) Specifically, QR is assumed

to apply in the following fashion: It replaces an indexed NP αi by a coindexed

trace, adjoins α (without the index!) to a dominating node, and prefixes the

sister constituent of α with a lambda operator indexed i. Schematically:

6For instance, I neglected the additional option of indexing the NP his mother.

207

Irene Heim

(4)

QR:

[S ... αi ... ] => [S α λi[S ... ti ... ] ]

For example, the result of applying QR to every boy 1 in (1a) is (1f).

(1)

f.

every boy λ1[t1 called his1 mother]

Our formulation implies that an NP needs to have an index in order to be able to

undergo QR; this means, e.g., that every boy cannot be QRed in (1c) or (1e).

This in itself presumably doesn't jeopardize the derivations, because quantifiers

in subject position are straightforwardly interpretable in situ, there being no

semantic type mismatch.

LFs are then submitted to the following definition of "variable" and the

associated filter.

(5)

a.

An index is a variable only if it is

(i) on a λ, or

(ii) on a trace and bound by a λ, or

(iii) on a pronominal or anaphor and A-bound.

b.

All indices must qualify as variables.

(5) cuts down on the number of possible derivations quite considerably. For one

thing, it implies that all (overt) NPs apart from anaphors and pronominals, in

particular all quantifiers and proper names, must wind up without an index.

This means they must either start out unindexed at SS, or else undergo QR and

thereby transfer their index to the λ. (Which makes QR effectively obligatory

for every boy1 in (1a,b,d).) From a semantic point of view, it makes sense not to

allow indices on quantifiers and names: on standard assumptions, the meanings

of such NPs are completely determined by the lexical entries for the words in

them and compositional rules; an index has no conceivable semantic

contribution to make and would thus have to be ignored anyway if it were

present.

(5) also implies that LFs cannot contain any free variables ("free" in the

sense of standard logic book definitions). For instance, the result of QRing only

every boy1 in (1b) is not a legitimate LF, because the index 2 is not sanctioned

by any clause of (5). (The only chance of rescuing this derivation would be by

QRing his2 as well.)

(1)

g.

* every boy λ1[t1 called his2 mother]

(5) moreover incorporates a version of the Weak Crossover prohibition, by

disallowing locally A-bar-bound pronouns. So the derivation (1a)/(1f) is wellformed, because the pronoun his1 winds up A-bound by the QR-trace t1, but its

counterpart with subject and object reversed would not be:

(6)

208

a.

SS:

his1 mother called every boy1

b.

LF:

* every boy λ1[his1 mother called t1]

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

The index on his in (6b) fails to count as a variable, because its only binder is

the λ rather than an A-position.

Finally, LFs are semantically interpreted . I can be informal about this

here, because how it works is mostly obvious. λ's, of course, are functional

abstractors. Variables in the sense defined in (5) are treated like variables in

logic (with occurrences of the same numerical index counting as occurrences of

the same variable, and occurrences of distinct numerical indices as occurrences

of distinct variables). A constituent that bears an index simply inherits the

interpretation of its index. For this reason, it is harmless and natural to refer to

the whole indexed NP as a "variable", though strictly speaking, the variable is

just the index.

Pronouns without indices are deictic and the utterance context has to

provide referents for them. Apart from sortal restrictions due to the pronoun's

gender, number, and person features, this reference assignment is a result of

interacting pragmatic factors, including salience and overall plausibility.

Moreover, it is constrained by the following principle, which constitutes the

most distinctive ingredient of Reinhart's approach.

(7)

Coreference Rule:

α cannot corefer with β if an indistinguishable interpretation can be

generated by (indexing and moving β and)7 replacing α with a variable

A-bound by the trace of β.

The next section is entirely devoted to illustrations of (7), which will also serve

to clarify some of the concepts it employs, notably "interpretation" and

"indistinguishability".

2. Reinhart's Coreference Rule applied to examples

This section parallels the discussion of the Coreference Rule in G&R, section

2.3. In particular, my example groups (ii) - (v) are all taken from their list, with

one systematic alteration: Since I am not dealing with Condition C effects at all

in this paper, I have replaced all apparent Condition C violations by similar

examples that look as though they violate Condition B.

2.1. Group (i): basic cases

Let's look at three primitive examples containing the proper name John and a

masculine singular pronoun.

(8)

John saw him .

(9)

John saw his mother.

(10)

His mother saw John.

7The parenthesized part of the instructions can be skipped if

β was already QRed in the

original structure.

209

Irene Heim

In each case, we are interested in the possible relations between the

interpretations of the name and the pronoun. This breaks down into two

questions: First, can the two stand in a variable binding relation? Second, can

they corefer? The predictions turn out to be the following: (8) allows neither

binding nor coreference; (9) allows binding but not coreference; and (10) allows

coreference but not binding. Here is how they are arrived at:

When we ask whether the him in (8) could be a variable bound by John,

we can't, of course, mean this quite literally; proper names are not variable

binders, after all. What we really mean is whether the pronoun could be a

variable bound by the λ that arose from QRing the name. So the question of

whether binding is possible in (8) turns on the well-formedness of the following

derivation.

(8)

a.

SS:

* John1 saw him1

b.

LF:

John λ1[t1 saw him1]

Though all indices in the LF (8b) qualify as variables and there is no obstacle to

interpretability, this derivation is already filtered out at SS by Binding Condition

B.

Could the two NPs corefer? For this we would need an LF as in (8c)

(trivially derived from an identical SS in which no NP was indexed) and an

utterance context that furnishes the reference assignments indicated by the

pointers underneath.

(8)

c.

LF:John saw him

↓

↓

j

j

I will make use of this notation to specify utterance contexts throughout the

paper: Each referring NP in the LF is connected by an arrow to its contextually

supplied referent. The lower-case letters stand for individuals out there in the

world, with each letter representing a unique individual and each individual

represented by a unique letter.

There would be nothing wrong with the interpretation indicated in (8c),

if it weren't for the Coreference Rule. This rule instructs us to look for an

alternative LF that results by certain specified alterations from that in (8c) and to

make sure that it wouldn't yield an indistinguishable interpretation. A potential

such alternative happens to be the LF we already saw in (8b), set in this context:

(8)

d.

LF:John λ1[t1 saw him1]

↓

j

This differs minimally from (8c) in just the way that (7) instructs us: Of our two

NPs in (8c) that were candidates for a coreferring pair, the first (John) has been

indexed and QRed and the second (his) has been replaced by a variable (his 1)

that is A-bound by the trace of the former. It is an interpretable LF,

notwithstanding the fact that it (because it would have to derive from a

210

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

Condition B violation at SS) is not part of a well-formed derivation for any

English sentence.8

Now we must determine whether there is any difference in the

interpretations of (8c) and (8d). Suppose for now this is to be done by

comparing the propositions expressed by each LF in its indicated context . It

turns out that these are the same: (8c) is true in any world where j saw j, and so

is (8d). So (8d) represents an indistinguishable interpretation from (8c), and

therefore the Coreference Rule says that (8c) is not a permissible interpretation

for (8). In short, the option of coreference in (8) is preempted by the existence

of (8d).

Let's turn to (9).

(9)

John saw his mother.

Here, binding is evidently predicted possible, the following derivation being

well-formed on both levels.

(9)

a.

SS:

John1 saw his1 mother

b.

LF:

John λ1[t1 saw his1 mother]

But coreference is not. A coreferential interpretation would look like this:

(9)

c.

LF:

John saw his mother

↓

↓

j

j

But under the Coreference Rule, this is preempted by (9d) (= (9b) plus a

context).

(9)

d.

LF:

John λ1[t1 saw his1 mother]

↓

j

Both of these express the proposition that j saw j's mother.

(As G&R acknowledge in footnote 13, it might be preferable to predict

this example to be ambiguous between a bound and a coreferential reading.

They suggest that this could be accomplished by a revision of (7) that confines

its application to those examples which involve prima facie violations of

Condition B, in a sense they make precise. I will adopt a similar proposal

below, but set the issue aside for the time being.)

8I have chosen to read (7) in such a way that the potential alternative structures to be

considered in applying this principle need not be part of complete grammatical

derivations. Alternatively, one might impose this further requirement, in which case the

him in (8c) would have to be replaced by a himself1 in (8d). Most renditions of Reinhart's

proposal seem to assume the latter. It doesn't seem to make any difference for the cases

considered here, but see footnote 12 of G&R (and apparently Reinhart (1991a), which I

haven't seen).

211

Irene Heim

In (10), we have the reverse prediction.

(10)

His mother saw John.

Binding is out, because (as we already saw with (6b)), the requisite structure

contains an index on his 1 that fails to qualify as a variable.

(10)

a.

* John λ1[his1 mother saw t1]

But coreference is, for this very reason, allowed. (10b) depicts the relevant

interpretation.

(10)

b.

LF:his mother saw John

↓

↓

j

j

This is not preempted by any other structure. Why not? Because the closest we

can come to constructing a potential competitor according to the specifications

of (7) is to index and QR John and coindex his with its trace, but then we have

precisely (10a), where his 1 is not a variable.

These three examples should have clarified some mechanical aspects of

the Coreference Rule. They also gave us the opportunity for a first stab at

elucidating the notion of indistinguishable interpretations, but we will soon see

that there is more to this notion than we have so far uncovered.

2.2. Group (ii): examples with only

(11) illustrates another type of example which has the superficial appearance of

a Condition B violation and which Reinhart cites in support of the Coreference

Rule. (I won't talk about analogous cases with other focussing particles such as

even.)

(11)

(Everybody hates Lucifer.) Only he himself pities him .

Why is (11a), with coreference, an available interpretation and not preempted by

the binding-alternative (11b)?

(11)

212

a.

only he himself λ1[t1 pities him]

↓

↓

l

l

b.

only he himself λ1[t1 pities him1]

↓

l

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

Well, that's obvious. We don't need to cast around for subtle differences here.

These two LFs have manifestly different truth conditions. (11a) says that

nobody besides Lucifer pities Lucifer , whereas (11b) claims that there are no

other self-pitiers.

Actually, a closer look at (11b) reveals a potential problem with this

application of (7). Notice that what corresponds to the α and β of (7) here are

the NPs him and he himself respectively. It is these two, after all, whose

coreference is to be licensed. When we construct the potential competing

structure according to the specifications of (7), we are supposed to coindex α

with the trace of β. But the trace t1 with which we coindexed him1 in (11b) is

not really the trace of he himself, but rather the trace of only he himself. That is

a different NP, and not a referring one, hence not a possible choice for β in the

first place.

In short, if this is indeed the way in which G & R intend the

Coreference Rule to apply to this example, then they must somehow be

assuming that for the purposes of (7), t 1 in (11b) counts as a trace of he himself.

That seems a little bit hokey, but there is something to be said for it. I will

return to the matter in section 5.3.3 below.

2.3. Group (iii): identity under debate

Coreference is systematically possible in Condition B configurations when we

are dealing either with explicit identity statements or with other utterances in

discourse contexts where the identity of the referents is unknown or at issue. A

representative example is the second to last sentence in (12).

(12)

A:

Is this speaker Zelda?

B:

How can you doubt it? She praises her to the sky. No competing

candidate would do that.

Nothing is wrong with this if the woman in question indeed is Zelda and the

pronouns thus corefer. Nothing is even wrong if the speaker knew this all along

and makes no secret of it. Reinhart's Coreference Rule is meant to throw light

on this well-known phenomenon.

Needless to say, variable binding is ruled out in the familiar way by

Condition B at SS. Coreference amounts to the following interpretation:

(12)

a.

she praises her to the sky

↓

↓

z

z

We must show that (12a) is not preempted under the Coreference Rule by any

other structure. A potential competitor with the right linguistic shape would be

(12b).

(12)

b.

she λ1[t1 praises her 1 to the sky]

↓

z

213

Irene Heim

If this doesn't qualify to preempt (12a), it can only be because its interpretation

is distinct. Is it?

Not if we just compare the propositions expressed. They are one and

the same, viz. that z praises z to the sky. So if we continue to interpret the

Coreference Rule in the way we did in the previous sections, it founders on this

example. Alternatively, we must look for a more suitable notion of

indistinguishable interpretation that will make it work right. The latter is, of

course, what Reinhart intends.

It is commonplace in the philosophical literature (especially on identity

statements) to distinguish the proposition expressed by an utterance from its

cognitive value . 9 When the utterance contains referring terms 10, the proposition

expressed depends only on their referents, but the cognitive value depends also

on the way these referents are presented. In the context of our example (12), for

instance, the person z presents herself to the interlocutors in two different

guises: First, they have a current visual impression of her, standing on the

platform over there and speaking. Second, they carry in their memory an entry

with various pieces of information about her, including that she is called

"Zelda".

Now when it comes to processing our sentence she praises her in (12),

what intuitively goes on seems to be this: Each of the two pronouns connects to

its referent z via one of these two guises. She, because of a perceived anaphoric

link to the subject this speaker of the preceding sentence, associates with the

visual impression; and her, through its link to the postcopular NP Zelda,

activates the memory entry. Therefore, the cognitive value of the sentence she

praises her to the sky for the hearer in this context is the proposition that

whoever causes the visual impression in question praises whomever the

pertinent memory entry represents. This is rather a different proposition from

the one the sentence expresses, viz. that z praises z.

More importantly for our present purposes, it is also different from the

cognitive value of the potential competitor in (12b). How so? Because (12b)

contains only one referring NP (she) and this will pick out its referent z via one

of the two guises salient in this context. Presumably this is the same one as for

the she in (12a), namely the visual impression. The cognitive value of the LF in

(12b) thereby comes to be the proposition that whoever causes this visual

impression praises herself—clearly a different proposition (with different

truthconditions) from the cognitive value of (12a) as described above.

The level of cognitive values thus seems to be more appropriate than

that of propositions expressed when it comes to distinguishing interpretations in

the sense of Reinhart's Coreference Rule. In this respect, our little diagrams

representing interpretations have been misleading or at least incomplete. An

utterance context for referring pronouns doesn't just supply these pronouns with

referents. Rather, it supplies them with guises, and these in turn happen to be

guises of something, namely the referents. The diagrams should thus contain an

9While some distinction along these lines is commonplace, many details and, of course,

the terminology vary from author to author. (The term "cognitive value", for instance,

comes form the introductory passage of Frege 1892, as translated by Max Black in Black

& Geach 1952.) For a thorough introduction and overview, see Haas-Spohn 1995.

10More accurately: directly referential terms in the sense of Kaplan 1989.

214

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

additional intermediate layer for the guises. (I use capital letters 'F', 'G', ... for

guises, with each letter standing for a unique guise and vice versa.) (12c)

replaces (12a), and (12d) replaces (12b).

(12)

c.

she praises her to the sky

↓

↓

F

G

↓

↓

z

z

d.

she λ1[t1 praises her 1 to the sky]

↓

F

↓

z

Semantically speaking, a guise is an individual concept, i.e. a function from

worlds to individuals. For instance, the visual impression alluded to above

(represented by 'F' in (12c,d)) can be viewed as assigning to each possible world

w the individual that it is an impression of in w. In the actual world of the

utterance, this is z, but in other worlds it may be someone else. The cognitive

value of (12c) is the proposition that is true in any w where F(w) praises G(w) to

the sky; that of (12d) is the proposition that is true in any w where F(w) praises

F(w) to the sky.

I will not formalize this any further, and in subsequent sections, I will

even fall back into the simplifying pretense that utterance contexts match

pronouns simply with referents. But before it's safe to do so, we should make

sure that the stories we told about (8) - (10) in the last section haven't collapsed

in the light of our refined notion of indistinguishable interpretation.

For instance, we took coreference between John and him to be ruled out

in (8) because (8d) preempted (8c). It did so, we said, because it expressed the

same proposition. But now we have seen that sameness of proposition

expressed is not a sufficient condition for indistinguishable interpretations. So

our argument re (8) is no longer conclusive. We should have established that

(8d) has the same cognitive value as (8c). Can this stronger argument be made?

Well, it can, if we bring out and exploit a tacit assumption about the example,

namely that it was meant to be judged either out of context, or in some sort of

run-of-the-mill context, say a conversation about John in his absence. In that

kind of ordinary setting, there wouldn't be multiple salient guises of j, but just

one (presumably the memory entry under his name), and the context would

assign that one to both the name and the pronoun in (8c). And in that case, the

cognitive values of (8c) and (8d) coincide, as desired. (Even if j happened to be

presented in two ways—say, he was visible in the distance during the

conversation about him—, this wouldn't suffice for the pronoun to automatically

link to him via a different guise than the name. For that to happen, the context

moreover has to contain appropriate clues that this is the intended

disambiguation.)

In short, we must qualify our earlier conclusion about (8): It doesn't

really follow from the grammar and the Coreference Rule alone that (8c) is

215

Irene Heim

unavailable; it only follows under additional assumptions about the context,

which imply that there is only one salient guise of j. But come to think of it, this

qualification is a good thing. It is a fact, after all, that even (8) could be used

with John and him coreferring if it were placed in an appropriately contrived

context.

There is much more to be said about the pragmatic conditions under

which contexts make two distinct guises of the same referent readily enough

available11, but let's move on.

2.4. Group (iv): when structured meaning matters

Evans (1980) emphasized a type of example that G&R likewise bring up in

illustration of the Coreference Rule. It will point us to yet another aspect of the

notion of indistinguishable interpretations. (The examples are again not exactly

Evans's or G&R's, but adaptations thereof to Condition B configurations.)

Consider the last clause of (13).

(13)

(You know what Mary, Sue and John have in common? Mary admires

John, Sue admires him, and) John admires him too.

Despite the Condition B environment, one sort of gets away with him referring

to John here. Apparently there is something about this particular preceding

discourse that makes it possible. What exactly is it and how does the

Coreference Rule predict it to matter?

The coreferential interpretation in question is (13a), and for some

reason it is not preempted by (13b).

(13)

a.

... and John admires him

↓

↓

j

j

b.

... and John λ1[t1 admires him1]

↓

j

11In Heim 1988:315 - 320, I proposed one concrete restriction: No context ever assigns

distinct but presupposedly coreferential guises to any pair of NP-occurrences.

(Definition: Guises F and G are presupposed to corefer in context c iff F(w) = G(w) for

every world w that conforms to the shared presuppositions of the discourse participants in

c.) This means that reference to the same object via two distinct guises is possible only

as long as the speaker still treats it as an open question whether indeed the same object is

behind these two guises. Once this is taken for granted (more accurately: presupposed in

the sense of Stalnaker 1979), only one guise is available. (This may be the result of

"collapsing" two previously available guises; in technical terms, the result of collapsing F

and G is F restricted to the set of worlds on which it coincides with G.) I still think this

proposal is defensible, though there are non-trivial issues to sort out (see, e.g. Landman

1986:104 - 105 for critical discussion). For the purposes of the present article, however, I

need not commit myself.

216

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

Why not? The propositions expressed are again identical, and there also don't

seem to be two different guises of j in this context that would lead to different

cognitive values. What then is the difference? It is, I think, the fact that two

different properties are predicated of j in (13a) and (13b): the property P of

admiring j in (13a), and the property Q of admiring oneself in (13b). In other

words, (13a) and (13b) express different structured propositions 12, <j,P> and

<j,Q>, even though they express the same unstructured proposition P(j) = Q(j) =

that j admires j.

Fair enough, but why does this suddenly matter? We could have

observed the same thing about all our earlier examples: there, too, the structured

propositions differed, even where we concluded that the interpretations were

indistinguishable. Evidently, differences in structured meaning do not always

matter. There has to be a special reason when they do. The special reason in

this case emerges when we analyze the preceding sentences: The speaker starts

out with a promise to tell what Mary, Sue, and John have in common. So we

expect him to mention a property that each of the three has. One particularly

direct and rhethorically effective way of doing this is to utter three predications

in which the same property is predicated of each of the three people in a row.

Now the first two predications, concerning Mary and Sue, were as follows:

(13)

c.

Mary admires John, Sue admires him, ...

↓

↓

↓

↓

m

j

s

j

Each of these predicates of its subject the property P of admiring j. Now if we

continue by (13a), we get a third predication of that same property. (13b), on

the other hand, would break the pattern and predicate a different property of j

than of the previous two people. It would still, of course, give us indirect

information about what the three have in common: we could determine the

shared property by a simple bit of deduction. But (13b) is more explicit, and

this, I submit, makes it beat out its competitor here and avoid being preempted.

A similar story applies to (14). This utterance, we are to imagine spoken by a

logic tutor.

(14)

Look, if everyone hates Oscar, then it surely follows that

Oscar (himself) hates him .

The intended interpretation is (14a).13

(14)

a.

if everyone hates Oscar, ... Oscar hates him

↓

↓

↓

o

o

o

Why isn't it preempted by (14b)?

12Structured propositions (and other types of structured meanings) have been put to

various uses in semantics; see Cresswell & Stechow 1982 for a recent example.

13Since subject quantifiers are interpretable in situ, I didn't bother to index and QR

everyone, but of course it wouldn't have hurt to do so.

217

Irene Heim

(14)

b.

if everyone hates Oscar, ... Oscar λ1[t1 hates him1]

↓

o

↓

o

Well, what the logic tutor is apparently trying to get across to the student is how

to apply the law of Universal Instantiation. (14a), as it happens, is a pure

illustration of that law: the predicates following everyone in the antecedent and

Oscar in the consequent denote the same property, that of hating Oscar. (14b),

by contrast, has the property of hating Oscar in the premise, but a different one,

that of hating oneself, in the conclusion. Of course, it is likewise a valid

inference. But its validity relies on more than just Universal Instantiation; it

collapses two inference steps (U.I. and λ-conversion). And that isn't optimal

didactic practice in this context.

So once again, a difference in structured meaning alone matters enough

to allow the interpretations (14a) and (14b) to count as distinct. But here as in

the previous example, this is due to very special circumstances: Logic teachers

have a professional duty to care not just about what proposition a sentence

conveys, but about how that proposition is built up from parts. For most

ordinary conversational purposes, however, the net message is all that counts,

and so we were right to disregard mere differences in structured meaning with

our earlier examples, and to disregard them again with most of the ones below.

2.5. Group (v): Lakoff's example14

Finally, why does one get away with utterances like (15), due to Lakoff (1972:

639)?

(15)

I dreamt that I was Brigitte Bardot and I kissed me.

The two underlined pronouns, being both first person, supposedly can't help but

corefer:

(15)

a.

... and I kissed me

↓

↓

g

g

('g' for George Lakoff, the speaker of (15).) But this interpretation ought to be

preempted by (15b).

(15)

b.

... and I λ1[t1 kissed me1]

↓

g

14This section is substantially changed from the previous version of this paper, partly in

response to questions raised by Higginbotham (p.c.) and Reinhart 1991b. Thanks to

Arnim von Stechow for reminding me of Stechow 1982. (McKay 1991 also looks

relevant, but I only received it when I was almost finished.)

218

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

Unless, again, we can argue that the latter has a distinct interpretation. That this

should be the case is made plausible by the observation that a minimally

different sentence, whose grammar forces the variable binding we see in (15b),

would actually describe a different dream:

(16)

I dreamt that I was Brigitte Bardot and I kissed myself.

(16) describes a dream about self-kissing, (15) doesn't. 15

Suggestive though this is, it is not so easy to show concretely how the

interpretations of (15a) and (15b) differ. The propositions expressed under the

reference assignments depicted in (15a,b) are certainly the same. The structured

meanings are different, but it is not evident why this should matter in this

context; at least there is no reason of the kind we found with (13) and (14)

above. Are the cognitive values distinct, then? For all we know so far, this

could only be if George Lakoff, as he utters (15), is somehow presented to his

audience in two separate guises, and that doesn't seem to be the case here either.

So where could the difference possibly lie?

To overcome this puzzle, we have to be a bit more precise on how such

examples are semantically interpreted. A suitable analysis of pronouns in

attitude reports, including an explicit application to (15), is found in Stechow

1982. Adapting his analysis (with some inessential alterations), let's begin by

positing a more articulate LF representation for attitude complements than we

took for granted in (15a,b). Following Quine 1956, believe, dream, and other

attitude verbs are logically 3-place predicates: the basic notion is for a subject to

believe (dream) something of something . The third argument (the "

res "argument) does not correspond to a surface constituent, but it is present at LF

and may be filled there by material moved out of the complement clause.16 For

instance, a simplified version of (15) (omitting the complement's first conjunct)

may have the following LFs, among others. (The corresponding SSs that these

should derive from in Reinhart's framework—all well-formed by the Binding

Conditions—appear in parentheses underneath.)

15Actually, the data are not quite so simple. The choice of the reflexive seems to be

compatible with both readings; at least this is my intuition about similar German

sentences:

(i)

Hans soll sich mal vorstellen, der Lehrer zu sein und sich/?ihn als Schüler zu

haben.

'Hans should imagine being the teacher and having himself/him as a student.'

The variant with the pronominal ihn is unambiguous as predicted by the analysis I will

sketch, though a little marginal (see below on what the marginality might be due to.) The

reflexive sich, however, also allows the pragmatically preferred reading, according to

which Hans imagines teaching Hans (rather than self-teaching). I have no account for

this reading. The analysis sketched in the text predicts only the self-teaching

interpretation here. Further research is required.

16Unfortunately, the syntactic distribution of

de re construals doesn't exhibit the

properties of movement. An "in situ" approach of the type that has proved successful for

association with focus would therefore be more appealing. The techniques for this are in

principle well worked out (see e.g. Rooth 1985) - except (to my knowledge) for the

interaction with variable-binding, which happens to be crucial in the present application.

219

Irene Heim

(15)

c.

I dreamt λ1[t1 kissed me] [ I ]

(SS: I dreamt I 1 kissed me )

d.

I dreamt λ1[I t1-ed me] [ kiss ]

(SS: I dreamt I kiss1ed me )

e.

I dreamt λ1,2[t1 kissed t2] [ I, me ]

(SS: I dreamt I 1 kissed me2 )

f.

I dreamt [ I kissed me ] [ ]

(SS: I dreamt I kissed me )

The "res-movement" that creates these LFs is like QR insofar as it involves λabstraction, but in some other respects operates quite differently: First, it isn't

Chomsky-adjunction, but substitution into a kind of argument position. Second,

it may affect phrases other than NPs (as in (d)). Third, it can apply multiply (as

in (e)). (If pure de dicto readings are to be covered as a special case, the res-slot

may also be left empty, as in (f).)

The semantic interpretation of the verb and its two internal arguments is

as follows: The left argument, denotes (as the λ-notation implies) a property of

n-tuples (n≥0, depending on the number of indices on the λ). The res-argument

denotes an n-tuple made up of the denotations of the phrases in it. The

interpretation of the verb is relative to a special contextual parameter, an n-tuple

of acquaintance relations in the sense of Lewis (1979). More precisely:

(17)

An LF of the form [α β γ [δ 1,...,δ n] ], where β is an attitude verb and n≥0,

requires an utterance context c which furnishes, for each i = 1, ..., n, an

acquaintance relation Dci.

To complete the analysis, take dream to mean 'believe in one's sleep'. In a given

context c, dream then denotes the following function f dream, c :

(18)

fdream, c (P)(<a 1,...,an>)(b) = 1 iff

(i)

b uniquely bears Dc1, ..., Dcn to <a1,...,an>, and

(ii)

b is asleep and self-ascribes the property of uniquely bearing

Dc1, ..., Dcn to some n-tuple of individuals satisfying P.

Now back to our example (15). Stechow proposes that (15) under the intended

reading has the LF-representation in (15c).17 The utterance context under

17It might actually be more accurate to assume (15e), with

both pronouns res-moved.

This would come to exactly the same reading if the second acquaintance relation supplied

by the context happened to be that relation which each individual bears to George Lakoff,

220

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

consideration (as before) assigns g as the referent to all three pronounoccurrences, and (by (17)) moreover supplies an acquaintance relation D. Here

is another picture to summarize these aspects of LF and context. (The pointer

under the verb indicates the contextually supplied acquaintance relation.)

(15)

g.

I dreamt λ1 [t1 kissed me] [ I ]

↓ ↓

↓

↓

g D

g

g

What is D? It is simply identity; this, at any rate, seems to be the choice that

yields the intuitively salient meaning. What the utterance asserts, then, is that g

self-ascribes in his sleep the property of kissing g. (The choice of identity for D

amounts to a so-called de se reading for the embedded subject; as Stechow

notes, this is usually the preferred reading for pronouns coreferential with the

higher subject.18)

Now, I think, we can finally see how G & R intend the Coreference

Rule to apply to this example. The me in (15g) is a referring pronoun that

corefers with the other two 1st-person pronouns in the sentence, in particular

with the embedded I that originates from a c-commanding position in its GC.

Why is this allowed?19 It would not be, (7) predicts, if (15g) meant exactly the

same thing as the following competitor with a bound variable:

(15)

h.

I dreamt λ1[t1 kissed me1] [ I ]

↓ ↓

↓

g D

g

In (15h), me has been replaced by a variable (me 1) A-bound by t1, the trace of I,

just as (7) demands. (The only difference compared to previous applications of

(7) is that the trace in question is a res-movement-trace, rather than a QR-trace).

(15h) has demonstrably different truthconditions from (15g): Given the same

value for D (identity), (15h) claims that g in his sleep self-ascribed the property

i.e. to that world-mate who is the actual Lakoff's counterpart by match-of-origins. It is

doubtful, however, that Lakoff knows enough about his origins to dream such a thing; see

Lewis 1984 for discussion. An advantage of (15e) over Stechow's choice (15c) would be

that the second pronoun could then be interpreted w.r.t. a similar, but probably more

realistic, acquaintance relation, say, the relation that x bears to y iff y is a world-mate of

x's who has the history and permanent characteristics that the actual George Lakoff

knows himself to have. But I will disregard this complication.

18For more discussion of de se readings and their status as special cases of

de re

readings, see Lewis 1979, Chierchia 1991, Higginbotham 1989, and Reinhart 1991b.

19Stechow also asks himself why (15) is not a Condition B violation, but his answer is

not quite sufficient for our present purposes. According to him, (15g) is okay because the

GC for me here is t 1 kissed me, which does not contain a coreferential c-commanding NP

(in fact, it contains no other referrring NP at all). But if this were good enough, why

couldn't we rescue every Condition B violation simply by QRing the offending

antecedent (e.g. as in John λ 1 [t1 saw him])? At any rate, it is not good enough for

Reinhart, whose theory we are assuming here. Under her assumptions, only looking at

(15g) itself is not enough to license it; we must also consider potential competing

structures.

221

Irene Heim

of self-kissing (the meaning earlier observed in sentence (16)). Hence (15h)

does not preempt (15g) and so (15g) is licensed.

3. Reference isn't special

Up to now I have merely tried to explain Reinhart's analysis. If I have gone

beyond plain repetition from G & R and her earlier publications, it was only to

flesh out details in the semantic analysis of certain examples, but not to add

anything that wasn't there yet, at least between the lines. In this section, I will

begin to disagree.

Let us look again at our fourth group of examples, the ones where

structured meaning mattered ((13) and (14)). Reinhart's account of them

captures an important intuition: These examples are licensed because of a

contextually important aspect of their meaning that would get lost if they were

replaced by their bound-variable counterparts. As such they call for a rule of the

kind of Reinhart's Coreference Rule, which essentially involves a comparison

between the meanings of two competing structures.

I still have a quibble, however: Is the phenomenon illustrated by (13)

and (14) really peculiar to referring NPs? Is it only referential pronouns that we

are sometimes allowed to use in unusual ways when a conversational purpose

justifies it? Come to think of it, such a limitation wouldn't be particularly

plausible to expect in an essentially pragmatic principle of this sort. And

indeed, once we start looking for the relevant examples, it isn't well supported

empirically either.

Recall, for instance, our logic tutor and his excuse for the coreferential

use of Oscar and him in (14). Once we let him get away with (14), are we really

going to put our foot down when he goes on as in (19)?

(19)

... And, of course, this doesn't just hold for Oscar, but for any arbitrary

man: If everyone hates a man, then that man himself hates him .

My point, of course, is that the last sentence in (19) is a donkey-sentence and the

two underlined NPs are donkey-anaphors, hence not referring terms. Under one

analysis of donkey-sentences, they are plainly bound variables, i.e., the LF

should be something like (19b), with a silent adverb of quantification equivalent

to a restricted universal quantifier (here abbreviated as "∀"). 20, 21

20Under an alternative (E-Type) approach to donkey-sentences, the donkey anaphors are

not plain bound variables, but descriptions of some kind, and the silent universal

quantification is not directly over men, but over cases. (See Neale 1990, Heim 1990, and

others for recent discussion.) Still, the donkey-anaphors are not referring terms under

that alternative either, because they would contain a bound case-variable, and so my main

point goes through all the same.

21It is not entirely obvious at this point how this LF is to be derived and licensed. One

revision to the present system that is surely required, once we bring in donkey-sentences,

is that indefinites on the one hand and demonstratives (and other complex definites) on

the other be allowed to count as variables, along with pronouns and anaphors. The

definition of variables also needs extending for donkey anaphors that are ordinary

pronouns, because these need not be A-bound. A suitable pair of added clauses might be:

222

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

(19)

a.

SS:

* if everyone hates [a man] 1,

[that man himself]1 hates him 1

b.

LF:

∀1 [ if [a man]1 [everyone hates t1] ]

[ [that man himself]1 hates him 1 ]

But this cannot be generated under Reinhart's assumptions: the derivation would

be blocked by Condition B at SS. There is no provision for licensing ill-formed

derivations like this, and the Coreference Rule is simply not pertinent here at all.

I take it that this is not satisfactory: (19) should be predicted to have pretty

much the same status as (14), with the choice of him over himself allowed for

the very same reason. Admittedly, (19) is (even) more contrived than (14) and

highly questionable from a pedagogical point of view. But it seems to me that

its added complexity is sufficient to account for what degradation we perceive

here. There isn't a qualitative contrast that would justify the special status of

referring pronouns that Reinhart's Coreference Rule in its present form grants

them.

And while you are in the appropriately contrived mind-set, consider a

bound variable variant of our other "structured meaning" example, (13):

(20)

Somebody said that what he had in common with his siblings was that his

sister admired him, his brother admired him, and he (himself) admired

him.

Again, it may not be the most natural English sentence, but the judgment isn't

such as to warrant a fundamental disparity between referential and bound

variable pronouns. My conclusion, therefore, is that Reinhart's Coreference

Rule captures the right intuition of what makes utterances like (13) and (14)

possible, but it should be made a little more general so that it covers (19) and

(20) as well.

Analogous points could be made about some of the other groups of

examples, but are more easily obscured there by murky technical details.

Recall, for instance, the only-example, whose intended interpretation is repeated

here:

(11)

a.

only he himself λ1[t1 pities him]

↓

↓

l

l

This, too, has bound-variable counterparts with much the same intuitive status.

For instance, (21) allows the reading in (21a).

(iv)

(v)

or on an indefinite in the restriction of a QAdv and A-bar-bound by it,

or on a definite in the nuclear scope of a QAdv and A-bar-bound by it.

223

Irene Heim

(21)

Every devil knows that only he himself pities him.

a.

∀x[devil(x) → know(x, that ∀y[y≠x → ~pity(y,x)])]

In Reinhart's system, this reading must have a derivation such as (21b,c).

(21)

b.

SS:

every devil1 knows that

[only [he himself]1]2 pities him1

c.

LF:

every devil λ1[t1 knows that

[ only [he himself]1 λ2[t2 pities him1] ] ]

Perhaps this is okay because no well-formedness constraint at either level rules

it out (in particular, the SS doesn't violate Condition B, because the adjoined

only blocks A-binding of him1 by [he himself]1). It is then not directly

problematic for Reinhart's theory. But isn't it a little strange if the explanation

for the acceptability of reading (21a) in (21) is so completely unlike the

explanation that was given for the acceptability of reading (11a) in (11)? The

latter involved comparison with potential preemptors under the Coreference

Rule, whereas the former relies entirely on considerations of syntactic wellformedness. We may suspect that a generalization is being missed here. It

would require some work to turn this suspicion into a real objection, but since I

won't let it carry the burden of my argument, I can afford to stop short of this

here.

The Lakoff-example likewise has bound-variable cousins, for instance

(22).

(22)

Not only I dreamt that I was Brigitte Bardot and I kissed me.

The relevant reading here is the one where (spoken by g) it says that there was

some x≠g such that x self-ascribed the property of kissing x (not to be confused

with the property of self-kissing). This seems no less acceptable than the

reading we have discussed for (15). But again, the explanation in Reinhart's

framework for why (22) allows such a reading cannot be anything like the

account given above for (15). Presumably, (22) has this reading because it

allows a derivation terminating in the following LF.

(22)

a.

not only I λ1[ t 1 dreamt that ... λ2[t2 kissed me1] [ I1 ] ]

It is not so clear at this point how such an LF is derived: what exactly is the SS

and why doesn't it violate Condition B? One way or another, these details must

be sorted out if the reading in question is to be generated. I will offer a concrete

suggestion below, but my present point doesn't depend on it. It is simply that,

whatever the details of an account of (22) in Reinhart's framework may turn out

to be, the Coreference Rule will not play any role in it. It couldn't, because there

is no coreference to be licensed (only a certain pattern of variable binding ). So

once again, what to the naive observer appears to be just a more complicated

224

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

instance of the same phenomenon receives a qualitatively different explanation - not, as it stands, a legitimate objection, but grounds for more suspicion.

The moral of this discussion seems to be that we should look for a more

general version of Reinhart's Coreference Rule, one that will cover bound

variable examples like (19) along with their simpler cousins involving

referential NPs, like (14). What we would like to replace (7) with is something

like the following:

(23)

Coreference-or-Cobinding Rule:

α cannot corefer or be cobound with β if an indistinguishable

interpretation can be generated by (indexing and moving β and) replacing

α with a variable A-bound by the trace of β.

This formulation presupposes a distinction between α and β being cobound on

the one hand and α being bound by (=cobound with the QR-trace of) β on the

other. (If "cobound" and "bound by" just meant the same thing, (23) would not

make sense, because then the cobound interpretation would be necessarily

indistinguishable from the one we are instructed to compare it to.) The

distinction is clear enough. For instance, [that man himself]1 and him1 are

cobound in our LF (19b) above, because each is bound by ∀1. If the latter were

to be bound by the former, the structure would have to look different, namely

like this:

(19)

c.

∀1 [ if [a man]1 [everyone hates t1] ]

[ [that man himself]1 λ2[t2 hates him 2] ]

The consequent clauses of (19c) and (19b) are logically equivalent, but they

differ in structured meaning, in just the way we have found to matter to the logic

tutor. So it is plausible that reading (19b) is available for (19) because of this

difference between it and (19c). (23), which predicts this, is on the right track.

The main point of this article is that (7) should be generalized to

something like (23), and having made that point, couldn't I stop here? I could if

it weren't for the following remaining loose ends and problems. First, I haven't

been able to be very precise yet about the treatment of the other types of

examples introduced in this section, i.e., (21) and (22). Second, (23) contains an

explicitly disjunctive formulation which it would be nicer to avoid. Third, even

with the generalized principle (23) in place of the former (7), the theory still

partitions the phenomena in a strange way: In coreference cases like (14), (23)

serves to license a certain interpretation for a grammatical derivation, but in

cobinding cases like (19) it acts to redeem an ungrammatical one. The actual

status of the examples does not warrant such a distinction; it would be better if

they were all grammatical, or all ungrammatical. Or, even better yet, if they

were all somewhere in between, which is what I will actually say below. I will

return to these points in section 5. The next section is devoted to an independent

criticism of Reinhart's system. The reason why I insert it at this juncture is that

it leads to some technical refinements that will be useful below.

225

Irene Heim

4. From coindexing to linking and codetermination

4.1. Bound variable pronouns that undergo QR

A technical difficulty arises when we ask what exactly happens when a bound

variable pronoun undergoes QR. Now I must first convince you that this

situation ever arises in the first place. To be sure, we have made QR completely

optional and unrestricted, so it would require a special stipulation to prevent it

from applying to bound variable pronouns. But do we really ever need to

exercise this option? The answer is 'yes': If we accept Reinhart's analysis of

ellipsis, there will be readings of English sentences that we can only generate by

QRing a bound variable pronoun.

This is not the place to launch into a detailed discussion of ellipsis. I

will just give a very brief exposition of Reinhart's approach and, for simplicity,

will concentrate entirely on Bare Argument ellipsis, setting aside any of the

additional complications that arise with the more common and colloquial VP

ellipsis. Consider a simple ellipsis structure:

(24)

I called John, and the teacher too.

(24) is ambiguous: the second conjunct can mean that the teacher called John,

or that I called the teacher. In the first reading, the "correspondent" of the

"remnant" the teacher is the subject I, in the second reading, the object John is

the correspondent.22 The basic idea, going back at least to Sag 1980, is that an

LF for the elliptical conjunct is derived by (a) QRing the correspondent in the

antecedent sentence, and (b) inserting a copy of the resulting λ−abstract next to

the remnant. Depending on the intended reading, this procedure yields (24a) or

(24b) for (24). (The copied material is in italics.)

(24)

a.

I λ1[t1 called John], and the teacher λ1[t 1 called John] too

b.

John λ1[I called t1], and the teacher λ1[I called t1] too

The semantic interpretation of these LFs is transparent.

In the two readings of example (24), the correspondents were a

referential pronoun and a proper name. But it is easy to construct similar

examples where the correspondent is a bound variable pronoun. A case in point

is the reading of (25) where it means that every boy said that I called both him

(the boy) and the teacher.

(25)

Every boy said that I called him, and the teacher too.

To derive the appropriate LF, we must QR the correspondent, which in this case

is the bound variable pronoun him. How exactly does this derivation proceed?

22The terminology of "correspondents" and "remnants" comes from the discussion of

Gapping in Pesetsky 1982.

226

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

First, what's the SS we start out from? Presumably, it has him coindexed with

every boy.

(25)

a.

SS:

every boy1 said that [I called him1, and the teacher too]

(The bracket just serves to indicate that the conjunction is in the lower clause.)

On the way to LF, both every boy 1 and him1 must QR, the former to bind the

pronoun, and the latter to create a constituent for ellipsis copying. So far, we

have assumed that QR applies in such a way as to shift the index on the moved

phrase over to the newly created λ next to it, so that the moved phrase itself

winds up unindexed. And this made sense in view of the fact that indices on

quantifying phrases like every boy (as well as indices on proper names and on

deictic pronouns) could make no semantic contribution anyway. However, if we

blindly applied QR to him 1 in exactly this same fashion, we get something

undesirable, namely (25b).

(25)

b.

every boy λ1[t1 said that

[him λ1[I called t1], and the teacher λ1[I called t1] too]]

The him has lost its index to the λ next to it and therefore is no longer bound by

(the λ next to) every boy. So (25b) cannot represent the intended reading.

It is not hard to think of ways to avoid this problem. The most obvious

and elegant option that comes to mind is to make the disappearance of the index

under QR simply optional: we are free to either retain the index of the QRed

phrase on both itself and the λ, or else—as before—to retain it only on the λ. In

most cases, we will effectively be forced to the second choice, because we

would otherwise end up with indexed NPs that don't qualify as variables under

(5). But nothing prevents us from retaining two copies of the index in the

special case where we are QRing a bound variable pronoun, and thus we can

derive an appropriate LF from the SS (25a), namely (25c).

(25)

c.

every boy λ1[t1 said that

[him1 λ1[I called t1], and the teacher λ1[I called t1] too]]

This expresses the intended meaning, and so we seem to have solved our

problem.

But wait, there is a complication: Consider the following slightly more

complex example:

(26)

Every boy said that [he called his mother and the teacher too].

This has many different readings, most of which are to be ignored here. We are

only interested in readings where (a) the correspondent of the the teacher is the

embedded subject he, and (b) both he and his are anaphorically related to every

boy. Still, there are two distinct readings that fit these specifications. The

difference comes out in the following two paraphrases for the elliptical conjunct:

227

Irene Heim

(26)

a.

... and the teacher called his own (the teacher's) mother.

b.

... and the teacher called his (the boy's) mother.

(26a) is a sloppy reading and (26b) a strict one. What SS and LF representations

are associated with each of these two readings?

Under our present assumptions, there is only one SS and LF available

to represent either reading: Because both he and his are to be bound variable

pronouns and anaphorically related to every boy, we can't but assign the

following indexing at SS:

(26)

c.

every boy1 said that he1 called his 1 mother and the teacher too

From there on, we have no real choices (not counting derivations that terminate

in uninterpretable LFs or leave the he unbound). Two applications of QR and

ellipsis copying yield (26d).

(26)

d.

every boy λ1[t1 said that

[he1 λ1[ t 1 called his 1 mother]

and the teacher λ1[ t1 called his1 mother] too]]

(26d) represents the sloppy meaning (26a). But for the other reading, the strict

one in (26b), we are left without any possible derivation.

4.2. Inner and outer indices

To remedy this limitation, I propose that we allow pronouns to be doubly

indexed at SS already. They can have an inner index that encodes what they are

bound by, and an additional outer index to encode what they in turn bind. (This

will be made more precise right below.) The inner and outer index need not be

the same.

Such dual indexing may look like a new-fangled notational contrivance,

but the distinctions it is meant to express are anything but new. Two

particularly important precedents are found in the PTQ fragment (Montague

1974) and in the Linking framework of Higginbotham 1983. Both of these

provide two different analyses for a sentence like (27) (a simplified version of

(26), without the elliptical conjunct).

(27)

Every boy said that he called his mother.

In PTQ, one option (call it (a)) is to build up a sentence with three occurrences

of the same free pronoun: he1 said that he1 called his1 mother, then use S14

with the operation F10,1 to quantify in every boy. In this derivation, both surface

pronouns are bound (=lose their subscripts) simultaneously in the last step.

Another option (b) would be to generate he2 called his 2 mother, then quantify

he1 into this to yield he1 called his mother, then build up further to he1 said that

he1 called his mother, and finally quantify in every boy with F10,1. This time,

228

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

the his was bound earlier in the derivation, whereas the he had a subscript until

the last step. 23 Of course, the meanings are equivalent, as one translation

reduces to the other by λ-conversion.

In Higginbotham's framework, (27) is generated with two different

linked structures:

(27)

a.

every boy said that he called his mother

↑↑__________|

|

|____________________|

b.

every boy said that he called his mother

↑_________|↑________|

These correspond respectively to the (a) and (b) derivations in PTQ. Given the

semantics for linked structures in Higginbotham 1987:125–127, 130–131, they

are again logically equivalent.

My double-indexing scheme mimics the two PTQ-derivations (a) and

(b) as follows:

(27)

c.

d.

SS:

[every boy]1 said that [he1] called [his1] mother

LF:

every boy λ1 [t 1 said that he 1 called his 1 mother]

SS:

[every boy]1 said that [he1]2 called [his2] mother

LF:

every boy λ1 [t 1 said that he 1 λ2 [t 2 called his2 mother]]

The LFs here and their intended semantics should be self-explanatory, but the

new SSs and SS-to-LF-changes call for some comments. Notice the distinction

between [αi] (inner index only), [α]i (outer index only), and [ αj]i (doubly

indexed). Regarding the operation of QR, I return to our original view that it

always works the same way. The trace retains the outer index of the moved

phrase, but the moved phrase itself transfers it to the λ and thereby loses it.

Bound variable pronouns are no exception. If an NP doesn't have an outer index

at SS, it just can't QR. On the other hand, if it does have one, it must QR, or else

23Of course, these are just two out of infinitely many derivations. For one thing, there

are infinitely many isomorphic derivations to each (a) and (b) where 1 and 2 are replaced

by different numbers. More interestingly, there are infinitely many additional derivations

not isomorphic to (a) or (b) which also yield the same meaning. Not all of these can also

be distinguished by means of my double indices. For instance, in PTQ we might build

he1 said that he1 called his 1 mother, then quantify in he2 with F 10,1, and then quantify in

every boy with F10,2. This derivation is not replicable in my system -- unless I were to

allow triple indices at SS, but I am not aware of any empirical motivation for this. There

are, however, some more types of PTQ-derivations besides (a) and (b) that do correspond

to distinct double-indices-representations; one of them will in fact become relevant right

below, see (26e) and (26g). (This footnote was prompted by questions raised by Barbara

Partee (p.c.). I am aware, of course, that I have not even begun to seriously explore the

expressive capacities of the proposed notation and its relation to alternatives in the

literature.)

229

Irene Heim

its outer index will fail to qualify on the following revised definition of

"variable" and the LF will be flitered out. (Note the change in clause (iii).)

(28)

Definition of "variable", revised:

An index is a variable only if it is

(i) on a λ, or

(ii) on a trace and bound by a λ, or

(iii) the inner index of a pronominal or anaphor and A-bound.

It follows that a bound variable pronoun that is to QR needs two indices: an

outer one in order to QR and an inner one in order to be bound.

Let's return to our problem with the strict-sloppy ambiguity in example

(26). Instead of the previous single option in (26c), we now have two choices

for representing (26) at SS, even when both pronouns are to be bound and the

subject is the correspondent:

(26)

e.

[every boy]1 said that [he1]2 called [his1] mother and the teacher

too

f.

[every boy]1 said that [he1]2 called [his2] mother and the teacher

too

(26f) is, of course, just like (27d) above; (26e) is like (27c) as regards the

indexing of his, but has an additional outer index on he (which we need to

enable it to QR, a prerequisite for ellipsis copying).24 Each of these derives a

unique LF:

(26)

g.

every boy λ1[t1 said that

[he1 λ2[ t 2 called his 1 mother]

and the teacher λ2[ t2 called his1 mother] too]]

h.

every boy λ1[t1 said that

[he1 λ2[ t 2 called his 2 mother]

and the teacher λ2[ t2 called his2 mother] too]]

And these correctly express the strict and sloppy readings respectively.

24Ignoring the elliptical conjunct, a PTQ derivation that corresponds to the indexing

choices in (26e) would proceed by building up he2 called his1 mother, quantifying in he1

by F10,2 to yield h e1 called his 1 mother, building up to he1 said that h e1 called his1

mother, and finally quantifying in every boy by F10,1. After the second step, this is like

derivation (a), and as in (a), both surface pronouns are bound simultaneously in the last

step.

230

Anaphora and Semantic Interpretation

4.3. The strong version of Condition B

We have now solved our initial technical problem about bound variable

pronouns undergoing QR, but we have yet to explore the repercussions of our

solution, especially for the operation of the Binding Conditions. With NPs

allowed to bear two distinct indices at once, there no longer is a unique obvious

notion of "coindexing," and thus of the Binding Conditions which rely on it.25

A variety of different coindexing-concepts are in principle definable, including

the following two:

(29)

Definition:

a.

b.

β is linked to α iff α's outer index = β's inner index.

α and β are colinked iff α's inner index = β's inner index.

The terminology is deliberately reminiscient of Higginbotham's linked

structures. It'll make sense to you if you glance at (27a,b) while applying the

definitions to (27c,d). In fact, linking as defined in (29a) has exactly the

properties of Higginbotham's linking relation; for instance, unlike coindexing it

is neither symmetric nor transitive.

Consider now Condition A. In the version used so far, it requires that

an anaphor be "coindexed with" a c-commanding A-position in its GC. How

should we reinterpret it in the present setting? Higginbotham proposes to

replace "coindexed with" by "linked to":

(30)

Condition A, new version:

An anaphor is linked to a c-commanding A-position in its GC.

(30) predicts that an SS such as (31a) is ill-formed.

(31)

a.

* [he1]2 cut [himself 1]

The reflexive, though in some sense "coindexed" with the subject, is not linked

to it in the sense of definition (29a). What (30) requires instead is the kind of

indexing shown in (31b).

(31b) [he1]2 cut [himself 2]

The semantic import of this prediction is that a reflexive must really be bound

within its GC, not just have a cobound antecedent there. To see this, look at the

LFs that (31a,b) give rise to:

25The reference to "A-binding", and hence to "coindexing", in LF-conditions like (28)

remains unproblematic, since all indices are single by the time we reach a well-formed

and interpretable LF.

231

Irene Heim

(31)

c.

from *(31a):

he1 λ2[t2 cut himself1]

d.

from (31b):

he1 λ2[t2 cut himself2]

The reflexive is free in (31c) and bound in (31d). Neither of these, of course, is

a well-formed LF on its own on our current assumptions, because of the free

index on he1 . But they might be part of larger well-formed LFs such as (32a,b).

(32)

a.

every boy λ1[t1 said that he1 λ2[t2 cut himself1]]

b.

every boy λ1[t1 said that he1 λ2[t2 cut himself2]]

These two happen to be logically equivalent, so we cannot observe right here

whether the prediction that (32a) comes from an ungrammatical SS is borne out.

But if we add an elliptical conjunct, the difference becomes manifest: (30)

predicts, correctly, I assume26, that (33)—unlike (26)—allows only a sloppy

reading.

(33)

[every boy]1 said that [he1]2 cut [himself *1/2] and the teacher too.

Now let's turn to Condition B. This used to require that a pronominal not be

"coindexed with" any c-commanding A-position in its GC. Should we again

replace "coindexed with" by "linked to"? If we have learned the lessons of

Partee & Bach (1984)27 or Higginbotham (1983; 1985), we know better than

that. Consider the following potential derivation for sentence (34):

(34)

every boy said that he called him

a.

SS:

[every boy]1 said that [he1]2 called [him1]

26More precisely: if (33) allows a strict reading as well, it does so no more easily than

(i).

(i)

John cut himself, and the teacher too.

Whatever relaxation of Reinhart's assumptions (here left untouched) about reflexives and

ellipsis will accommodate a strict reading in (i) should do so for (33). I don't mean to

dismiss the issue of strict readings with reflexives or diminish its potential significance