The Harper Anthology Volume XXVII 2015

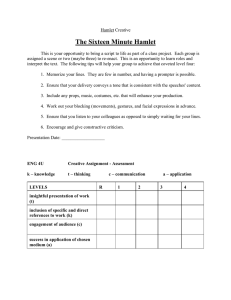

advertisement