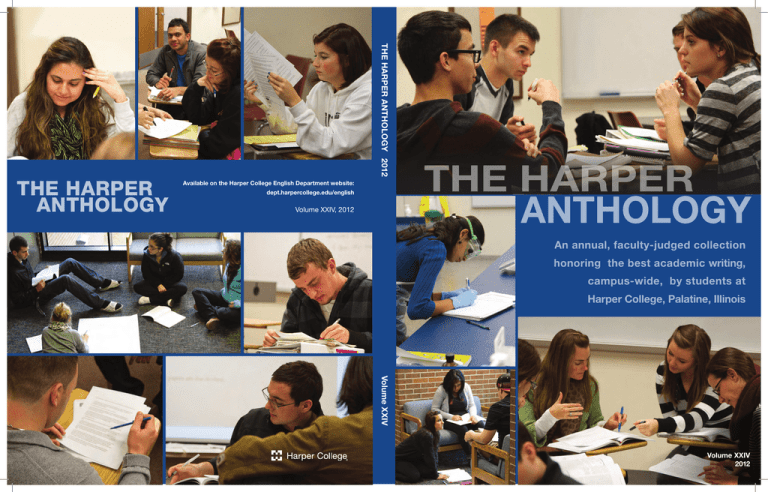

Harper Anthology 2012: Student Academic Writing Collection

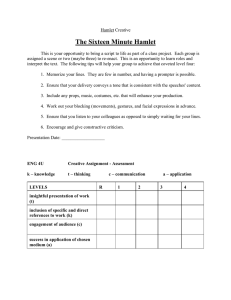

advertisement