Document 12575136

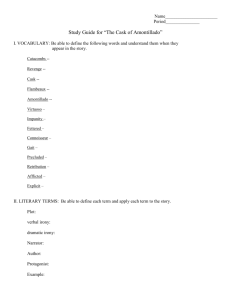

advertisement