Extensive archaeological studies are providing new evidence for the links... fluctuations and cultural change.

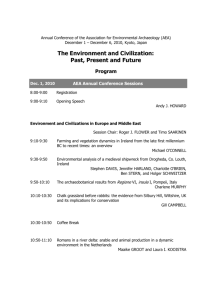

advertisement

EUROEVOL Boom and bust Extensive archaeological studies are providing new evidence for the links between population fluctuations and cultural change. Professor Stephen Shennan discusses the relevance of these findings for informing social, cultural and economic modelling of both the past and present How are you integrating cultural evolutionary theory and method? There are increasing numbers of archaeological studies that have focused on a single process, such as modelling the factors affecting the transmission of artefact style, from an evolutionary perspective. Bringing together different sub-fields of cultural evolutionary theory and method in a case study depends on collecting a range of data relating to different aspects of past economy, society and culture so that the relations between them can be explored. This is extremely time consuming and therefore expensive. It is only funding on the scale of the European Research Council Advanced Grants that makes this possible. What progress have you made since the EUROEVOL project started in 2010? Project members have devoted most of their time to data collection. This has involved building a database of more than 13,000 radiocarbon dates and establishing the grid references of the sites concerned so that we can carry out spatial analysis of the data. In addition, we have been collecting information on plant and animal remains from excavated sites to reconstruct the changing subsistence economy, as well as on movement of raw materials (such as stone for axes) and on variation in material culture (such as pottery and ornament styles as evidence for patterns of social interaction). The key to the work is the reconstruction of population patterns. This has involved the development of a new method for using radiocarbon dating as a demographic proxy and testing the resulting patterns for statistical significance. We have shown a striking pattern of boom and bust. Who makes up the EUROEVOL Network, and what skills do these individuals add to the investigation? The core of the Network is the team of postdoctoral fellows employed by the project. This includes specialists in the analysis of archaeological faunal and botanical assemblages; radiocarbon dating; material culture and sites of the European Neolithic period; and modelling, data analysis and databases. Currently, there are four full-time and two part-time postdoctoral research assistants. In addition, we collaborate closely with Professor Mark Thomas of University College London (UCL) – a geneticist, who provides relevant population genetics expertise – and Dr Anne Kandler of City University, London, who is a mathematician. We have also worked with Dr Andy Bevan from the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, who is a specialist in spatial analysis; Dr Jutta Lechterbeck from Germany, a pollen analysis specialist; and Professor Neil Roberts and his team from the University of Plymouth whose environmental history project called ‘Deforesting Europe’ provides data on the history of human impacts on the environment, representing an independent source of evidence to cross-check our demographic reconstructions. To what extent is a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach important to this type of study? Basically, the project would be a non-starter without the integration of all these different areas of expertise. All areas of archaeological and environmental evidence require very specific knowledge if they are to be used correctly – obviously an absolute requirement before the relationships between them can be explored. Statistical modelling has to be tailor-made to the problems being addressed and this cannot be achieved simply by using standard packages. Can your methods be applied to inform societal modelling of any period and region? It has been possible to show links between changing population density and the incidence of violence, the scale of flint-mining and early metal exchange, and it is also apparent in a number of cases that the rise and decline of regional cultures is associated with that of regional populations. This approach can certainly be used to inform the modelling of social, cultural and economic systems in any region and period, including the present. I would hope that our work can be a kind of model case study that specialists investigating other periods and areas would be interested in following. In this sense, I think what is most significant is putting population at the core of the system and asking: what causes population booms and busts, and what consequences do they have? This is very relevant to the global future, in which the world population will soon reach 10 billion, as well as to the past. WWW.RESEARCHMEDIA.EU 99 EUROEVOL Charting cultural evolution Researchers involved in the EUROEVOL project are employing a novel evolutionary perspective and advanced statistical techniques to delve into how farming helped to transform early European societies THE LAST TWO decades have seen an emergence of new interdisciplinary research looking at how cultures have evolved. In particular, these have focused on using Darwin’s theory of evolution to understand more about how human societies and cultures have changed and advanced over time. This crosscutting field offers the potential for exciting insights into how humans have developed throughout history. As the archaeological record provides factual information and data on social change over a long period, there is great potential to build on existing knowledge from a new evolutionary perspective and reveal previously unknown information. This fresh approach is being applied by the Cultural Evolution of Neolithic Europe (EUROEVOL) team which is aiming to identify links between demographic, economic, social and cultural patterns and processes by bringing together a number of different disciplines and applying these to large-scale case studies in history. STUDYING EARLY FARMING POPULATIONS Project coordinator Professor Stephen Shennan from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London in the UK explains how the theory of evolution can be applied to human behaviour: “Just as Darwin’s theory provides a framework that links studies of dinosaur fossils with investigations of primate behaviour and the development of drug-resistant bacteria, so the cultural adaptations of that theory link studies of changing pottery types with 100INTERNATIONAL INNOVATION psychological experiments and sociolinguistics, enabling microscale social and psychological mechanisms to be linked to longer term adaptation and history”. The EUROEVOL group is using this approach to investigate how farming helped to change Western European societies during the period circa 6000-2000 BC. This timeframe is significant because it covers the introduction of farming, which began around 7,500 years ago in Central Europe and 6,000 years ago in the North West, and runs until the beginning of the Bronze Age, about 4,000 years ago in this region. The investigators are focusing on farming because it is widely agreed to be the most fundamental development in human history until the Industrial Revolution, as Shennan explains: “It made possible much larger populations, changed human diets and laid the foundations for more complex and hierarchical societies”. Aiming to highlight some of the benefits and weaknesses of linking the use of cultural evolutionary theory and methods to look at long-term change, EUROEVOL mainly focuses on the history of human populations because this is at the intersection of many key issues. “For example, economic factors such as the development of farming can lead to population expansion, which can create new opportunities for innovation, new forms of social organisation and result in the spread of new languages with their speakers,” notes Shennan. By studying and reconstructing the population histories of early European societies over the long term, the researchers can explore how and why those patterns formed. DEVELOPING NOVEL STATISTICAL METHODS Most of the work centres around archaeological data, which are fundamentally quantitative in nature. This means that corresponding methods of data analysis are needed to enable the researchers to identify patterns. In addition, the location and date of these data are important to help understand how cultures evolved. The team is using spatial and temporal forms of analysis to interpret this information and has adopted a new approach which models the processes thought to underlie the patterns seen and compares the outcomes with real-world information. This process allows the researchers to identify any statistically significant differences. An example of how the team’s methods are being put into practice can be seen in its study of the demographic impact of the arrival of farming. One of the challenges the group had to overcome is that the measure they use as a demographic proxy – the number of sites present at a given time dated by the radiocarbon method – does not have a linear relationship with calendar years. To overcome this difficulty, they created a novel way to test the significance of departures in the data from the long-term exponential trend in human populations, taking into account the nonlinearity of radiocarbon time in relation to real time. The group has also successfully improved the methods which have been used over the last decade to test the neutral model of cultural transmission, recently publishing the results Reconstructed demography for four different regions of the UK and Ireland, 8,000-4,000 years ago. The black line shows the pattern of long-term exponential increase in population that is to be expected on the basis of continental and global population trends. The red areas mark periods when population was significantly higher than expected on the basis of the long-term trend, the green areas periods when it was lower. Farming, and most probably farmers themselves, arrived in the UK and Ireland circa 6,000 years ago. in the Journal of Theoretical Biology. “This is a model derived from population genetics, extensively used in evolutionary archaeology in recent years, that generates the frequency of different cultural traits under the assumption that they are not under any kind of selection,” adds Shennan. REVOLUTIONISING ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT HUMAN HISTORY This work has the potential to transform the way early human history is viewed. The innovative methods Shennan and his team use to obtain and analyse data about past cultures provide valuable new evidence for how societies developed and evolved in early Europe, and in theory for other societies. A paper by EUROEVOL researchers presenting evidence of demographic booms and busts in Neolithic Europe has just been accepted by Nature Communications. This kind of information has previously been inaccessible because it requires appropriate analysis of data with a high level of chronological resolution. Far from the prehistoric past being static and unchanging, the results point towards a past that was far more dynamic than generally assumed. There are two main reasons why this work is pioneering. First, the theoretical framework of cultural evolution, and consequently the history of human populations, is still being developed. Second, if population is crucial then a reliable method to reconstruct population history is needed, as Shennan elaborates: “This has been a controversial subject in archaeology but new data are becoming available and new techniques are increasingly making it possible to use the data, including new statistical methods that we have been developing in EUROEVOL to use radiocarbon dates as a proxy for population”. This research has demonstrated that high population levels in early farming systems were not maintained and, for the first time, shown a pattern of prosperity and decline in Neolithic populations that is not linked to a changing climate. EUROEVOL will be entering its final stage next year. The researchers’ task in the remaining time will be to continue to explore the relationships between the population histories that are being reconstructed for different regions of Europe and the social, economic and cultural patterns being characterised. Shennan is now in a position to start thinking about possible aspects of this topic to follow up with future research projects. For instance, more work is needed to understand the social, cultural and economic factors at play following regional collapse in populations. Far from the prehistoric past being static and unchanging, the results point towards a past that was far more dynamic than generally assumed INTELLIGENCE CULTURAL EVOLUTION OF NEOLITHIC EUROPE (EUROEVOL) OBJECTIVES To answer the following questions: • How did regional population patterns change circa 6000-2000 BC? • What are the links between subsistence, climate change and social institutions, on the one hand, and population patterns on the other? Do the population patterns reflect periods of economic growth and decline? • To what extent were population fluctuations the main source of cultural change? • What are the links between cultural patterns in space, for example monumental and ceramic traditions, and the nature and extent of social interaction? • Is it possible to identify the existence of longstanding cultural ‘cores’ subject to descent with modification in different times and places, or is a model of different distinct cultural ‘packages’ more appropriate? KEY COLLABORATORS Professor Mark Thomas, Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, UK • Dr Sean Downey, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, USA • Dr Anne Kandler, Mathematics Centre, City University, London, UK • Dr Jutta Lechterbeck, Baden-Württemberg Landesdenkmalamt, Germany • Professor Neil Roberts; Dr Ralph Fyfe; Dr Jessie Woodbridge, School of Geography, University of Plymouth, UK FUNDING European Research Council Advanced Grant #249390 CONTACT Professor Stephen Shennan Principal Investigator Director, Institute of Archaeology University College London 31-34 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PY, UK T +44 207 679 7483 E s.shennan@ucl.ac.uk www.ucl.ac.uk/euroevol/EUROEVOL/Home. html PROFESSOR STEPHEN SHENNAN received his BA and PhD in Archaeology from the University of Cambridge. He then held a number of positions at the University of Southampton. In 1996, Shennan moved to the Institute of Archaeology, University College London as Professor of Theoretical Archaeology. 2005 saw him become Director of the Institute of Archaeology, and the following year he was made a Fellow of the British Academy. Since the late 1980s, his interests have mainly focused on exploring the use of method and theory from the study of biological evolution to understanding cultural stability and change. WWW.RESEARCHMEDIA.EU 101