‘Transportation is Civilisation’: Ezra Pound’s Poetics of Translation Andrés Claro

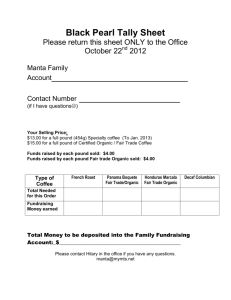

advertisement