This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The... copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

advertisement

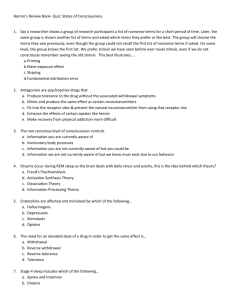

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Affective Disorders j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j a d Review Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies Chiara Baglioni a,⁎, Gemma Battagliese b, Bernd Feige a, Kai Spiegelhalder a, Christoph Nissen a, Ulrich Voderholzer a,c, Caterina Lombardo b, Dieter Riemann a a b c Department of Psychiatry & Psychotherapy, University of Freiburg Medical Center, Hauptstraße 5, 79104 Freiburg, Germany Department of Psychology, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Via dei Marsi 78, 00185 Roma, Italy Medizinisch-Psychosomatische Klinik, Am Roseneck 6, Prien, Germany a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 17 November 2010 Received in revised form 10 January 2011 Accepted 11 January 2011 Available online 5 February 2011 Keywords: Insomnia Depression Longitudinal Epidemiologic Predictor Meta-analysis a b s t r a c t Background: In many patients with depression, symptoms of insomnia herald the onset of the disorder and may persist into remission or recovery, even after adequate treatment. Several studies have raised the question whether insomniac symptoms may constitute an independent clinical predictor of depression. This meta-analysis is aimed at evaluating quantitatively if insomnia constitutes a predictor of depression. Methods: PubMed, Medline, PsycInfo, and PsycArticles databases were searched from 1980 until 2010 to identify longitudinal epidemiological studies simultaneously investigating insomniac complaints and depressed psychopathology. Effects were summarized using the logarithms of the odds ratios for insomnia at baseline to predict depression at follow-up. Studies were pooled with both fixed- and random-effects meta-analytic models in order to evaluate the concordance. Heterogeneity test and sensitivity analysis were computed. Results: Twenty-one studies met inclusion criteria. Considering all studies together, heterogeneity was found. The random-effects model showed an overall odds ratio for insomnia to predict depression of 2.60 (confidence interval [CI]: 1.98–3.42). When the analysis was adjusted for outliers, the studies were not longer heterogeneous. The fixed-effects model showed an overall odds ratio of 2.10 (CI: 1.86–2.38). Limitations: The main limit is that included studies did not always consider the role of other intervening variables. Conclusions: Non-depressed people with insomnia have a twofold risk to develop depression, compared to people with no sleep difficulties. Thus, early treatment programs for insomnia might reduce the risk for developing depression in the general population and be considered a helpful general preventive strategy in the area of mental health care. © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Contents 1. 2. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.1. Search method for identification 2.2. Studies selection . . . . . . . . 2.3. Data extraction . . . . . . . . . . of . . . . . . . . . . studies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: + 49 761 270 6589; fax: + 49 761 270 6619. E-mail address: chiara.baglioni@uniklinik-freiburg.de (C. Baglioni). 0165-0327/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 11 11 12 12 Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 2.4. Meta-analytic calculations . . . . . . 2.5. Publication biases . . . . . . . . . . 2.6. Incidence of depression . . . . . . . 3. Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.1. Total sample . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.2. Sensitivity analysis: excluding outliers 3.3. Subgroup analysis: age groups . . . . 3.4. Publication bias . . . . . . . . . . . 3.5. Incidence of depression . . . . . . . 4. Discussion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Role of funding source . . . . . . . . . . . . . Conflict of interest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1. Introduction Depression is the leading cause of disability in both women and men in the United States and worldwide and one of the 10 leading disorders for global disease burden (Lopez et al., 2006). In the United States, it has been reported that each year more than 19 million adult Americans suffer from a depressive illness and the direct and indirect costs of the disorder are more than $30 billion (Lopez et al., 2006). However, consensus reports show that individuals with depression are being underdiagnosed and undertreated (Hirschfeld et al., 1997). Although a substantial increase in the prescription of antidepressants has been observed over the past twenty years, data suggest that this increase is mainly due to increased long-term prescribing, rather than to changes in the recognition or case definition of depression (Moore et al., 2009). In order to narrowing the gap between prevalence and primary care assistance, the recognition of clinical early predictors of depression seems of utmost relevance. Major depression commonly co-occurs with symptoms of insomnia (Riemann and Voderholzer, 2003; Tsuno et al., 2005), defined in the DSM-IV-TR as difficulties in initiating/maintaining sleep or non-restorative sleep, accompanied by decreased daytime functioning, persisting for at least four weeks. Already 40 years ago, Winokur et al. (1969) described in a sample of 1257 individuals with depression that all of them had insomniac symptoms. Although this relationship between depression and insomnia is well known and its description dates back to the founder of modern psychiatry (Kraepelin, 1909), its conceptualization has radically changed during the last decade. Insomnia has been traditionally conceptualized as a symptom of psychopathology, especially depression (overview see Riemann et al., 2001; Staner, 2010). More recently, insomnia has been considered as a primary disorder if it is present without the co-existence of other clinically relevant psychiatric or medical diseases, and as a secondary disorder if otherwise. Nevertheless, with respect to the link to depression, chronic insomnia can also exist years before the first onset of a depressive episode. Consequently, it has been suggested that “comorbid” insomnia may be a more appropriate term than “secondary” insomnia (McCrae and Lichstein, 2001; NIH, 2005; Lichstein, 2006). This new approach identifies insomnia and depression as two independent diagnostic entities with different clinical courses and characteristics (Staner, 2010). The next edition of DSM, DSM-V, will probably abandon the . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 12 12 13 15 15 15 15 16 16 17 17 18 primary/secondary concept and instead introduce “insomnia disorder” as the main diagnostic category for insomnia, allowing specification whether or not it is co-morbid with another mental or medical disorder (Reynolds and Redline, 2010). The close link between insomnia and depression suggests that the conditions are not just randomly associated. Insomnia is now considered not only a symptom of but also a possible predictor of depression. Ford and Kamerow (1989) were the first to note that such a relationship exists based on data from a longitudinal epidemiological study. Since then more than 40 studies have been published evaluating the predictor question (overview see Riemann, 2009; Baglioni et al., 2010a). However, despite the large amount of data collected up to now, no systematic meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal studies has been performed about this type of relationship. Such an analysis might have strong clinical implications. If insomnia is indeed a predictor for depression, early and adequate treatment of insomnia might contribute to the prevention of the future development of depression. This view seems to be supported by some studies showing that adding cognitive-behavior treatment for insomnia (CBT-I) is efficacious also in patients with both symptoms of insomnia and depression and guarantees a better treatment outcome in this population than standard antidepressive treatment alone (Taylor et al., 2007; Manber et al., 2008). The aim of the current review was to quantitatively summarize the results of studies which have longitudinally investigated the role of insomnia as a predictor for depression with a meta-analytic strategy. We hypothesized that symptoms of insomnia predict depression in different age-samples. 2. Methods The meta-analysis was performed according to the MOOSE (Stroup et al., 2000) and the PRISMA (Liberati et al., 2009) guidelines. The first and second authors independently conducted the literature search, screened the titles and the abstracts of potentially eligible studies identified, examined the full text and extracted the data for the analyses from the selected studies. 2.1. Search method for identification of studies Longitudinal studies were identified via literature search using PUBMED, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and PsycArticles and Author's personal copy 12 C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 performed for all languages. The search was conducted from 1980 until February 2010. Indeed, as the DSM III was published in 1980, studies published before did not have the possibility to refer to the modern definition of psychiatric conditions. Key search terms included: “insomnia” linked to “depression” and “longitudinal” or “epidemiology” or “prospective” or “risk factors”. Terms were searched as keywords, capturing the title and abstract. Further studies were added by examining the reference lists of the papers found by the literature search. Unpublished studies were not included. 2.2. Studies selection After a first screening of titles and abstracts, the full texts were examined to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Studies were only considered when “sleep problems” were defined as difficulties in initiating/maintaining sleep or non-restorative sleep (i.e. insomniac symptoms). Moreover, studies were selected only if depression was measured through standard measures or consistently with the DSM IV definition. Additionally, studies were included only if participants with significant depression at baseline were excluded for the analysis or if the effect of symptoms of insomnia in predicting depression was controlled for other depressive symptoms. Only those studies in which odds ratios were reported or computable from the given data were selected in order to compute meta-analytic calculations. Additionally, studies were considered only if the follow-up measurement was conducted after at least 12 months in order to evaluate the long-term relationship between insomnia and depression. First authors were contacted for supplemental data to the published information. All authors contacted replied confirming or adding information about the suitability/unsuitability of their study for the meta-analysis calculations. 2.3. Data extraction For each study, data on a number of procedural variables were collected in order to assess the quality of the studies. Specifically, the variables considered were: sample size, length of the follow-up period (in months), and definition of insomnia on the basis of DSM-IV-TR criteria. With respect to the definition of insomnia, three groups were identified: meeting only the sleep difficulties criterion (difficulties in initiating/maintaining sleep or non-restorative sleep); meeting the sleep difficulties and the duration criteria (at least 1 month); meeting the sleep difficulties, the duration, and the daytime consequences criteria. Additional descriptive information collected were gender, age, publication year, and number of follow-up assessments. Furthermore, in order to compute meta-analytic parameters for dichotomous outcomes, for each study the odds ratio was collected with 95% confidence intervals (CI), as index of the predictive value of insomnia for future onset of depression. 2.4. Meta-analytic calculations The logarithms (logs) of the odds ratios and their CIs were used for meta-analytic calculations. The analysis was applied to the whole sample of studies and the studies were pooled with both fixed-effects and random-effects meta-analytic models.That is, the concordance between the two models supplies first information concerning heterogeneity among the studies: if the fixed and the random models give identical results it is unlikely that there is important statistical heterogeneity. In contrast, if the two models vary, heterogeneity needs to be assessed. In order to test for heterogeneity, chi-square tests and the I2 statistic derived from the chi-square values were used. I2 describes the proportion of total variation in the estimates of effect size that is due to heterogeneity among studies (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). An alpha error b0.20 and an I2 of at least 50% were taken as indicators of heterogeneity. Based on the results, we considered the fixed-effects model when studies were not heterogeneous, as a fixed model assumes that all studies share a common true effect size (Borenstein et al., 2009). If studies were heterogeneous, a random-effects model was used. In sensitivity analyses, we considered standardized residuals to identify outcomes that were outliers. Studies with standardized residuals greater or equal to + 3 and/or lower or equal to − 3 were deleted from the analysis (Hedges and Olkin, 1985), and the meta-analytic calculations were performed again. Moreover, a subgroup analysis was conducted considering 4 age groups and performing the meta-analytic calculations for each group: 1) children and adolescents, 2) working-age, 3) elderly, 4) mixed-age. All meta-analytic calculations were made with the software program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2 (Borenstein et al., 2006). 2.5. Publication biases Potential publication or retrieval bias was assessed using visual assessment of the funnel plot. This was computed considering the standard error of the log odds ratio against the log odds ratio. Publication bias may lead to asymmetrical funnel plots. Furthermore, we tested the sensitivity of our results to potential unpublished studies using the revisited file-drawer test for meta-analysis (Rosenberg, 2005). This test determines the number of non-significant, unpublished (or missing) studies that would need to be added to a meta-analysis to reduce an overall statistically significant observed result to non-significance. This number is called the “fail safe number”. If the number is large relative to the number of observed studies, one can feel fairly confident in the summary conclusions. 2.6. Incidence of depression Incidence of depression was considered for those studies which reported: a) the percentage relative to the incidence of new episodes of depression; b) the number of individuals with sleep difficulties and no depression at baseline who developed new depression at follow-up and the number of individuals with no sleep difficulties and no depression at baseline who developed new depression at follow-up. For those studies a mean percentage indicating the incidence of depression in the two groups with and without sleep difficulties was calculated. Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 3. Results Fig. 1 illustrates the search flow. The literature search yielded 46 longitudinal studies considering both sleep difficulties and major depression. Five studies were excluded as they focussed on the effect of depression predicting sleep difficulties (Morgan et al., 1989; Hohagen et al., 1993; Foley et al., 1999a; Patten et al., 2000; Jansson and Linton, 2006). Two studies were excluded because the follow-up assessment was conducted after less than 12 months (Hohagen et al., 1994; Schramm et al., 1995). Three studies were excluded as sleep difficulties were defined only as excessive sleepiness (Barkow et al., 2001), intake of sleeping pills (Harlow et al., 1991), or “sleep rhythm” problems (Ong et al., 2006). One study was excluded as the odds ratio was not reported and not computable (Rodin et al., 1988). Finally, one study was excluded because it focussed on the risk for non remission of depression, instead of new onset of the disorder (Pigeon et al., 2008); and one study was excluded because it focussed on the risk for suicidality, instead of the onset of depression (Cukrowicz et al., 2006). A further selection was made in order to ensure homogeneity of insomnia definitions. Specifically, 4 studies were excluded as insomnia was considered together with hypersomnia and parasomnias in a single variable (Gregory and O'Connor, 2002; Gregory et al., 2005; Gregory et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2009). Eight more studies were excluded as an unspecified variable “sleep disturbances” was taken into account as predictor (Kennedy et al., 1990; Dryman and Eaton, 1991; Green et al., 1992; Livingston et al., 1993; Paffenbarger et al., 1994; Berger et al., 1998; Prince et al., 1998; Livingston et al., 2000). Our final selection included 21 studies. Table 1 shows the list of the studies and the description of the study characteristics. The mean sample size at the followup (t1) was n = 3200 (sd = 5556), ranging from n = 147 (Perlis et al., 2006) to n = 25,130 (Neckelmann et al., 2007). 13 The mean age of the participants was 46 years (sd = 22.4) with means ranging from 6 (Johnson et al., 2000) to 80 years (Foley et al., 1999b). In 3 studies, the age of the participants was b18 years — a) children and adolescent group (Johnson et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2002; Roane and Taylor, 2008). Seven studies considered working-age adults — b) workingage group. In 6 studies, the age of the participants ranged between 18 and 60 years (Vollrath et al., 1989; Breslau et al., 1996; Chang et al., 1997; Mallon et al., 2000; Buysse et al., 2008; Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom, 2008). In one of these 7 studies, the age of the participants ranged between 33 and 71 years, but all participants were employees (Szklo-Coxe et al., 2010). In 6 studies, the age of the participants was N60 years — c) elderly group (Brabbins et al., 1993; Foley et al., 1999b; Hein et al., 2003; Perlis et al., 2006; Cho et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009). In 4 studies, working-age adults and elderly were considered together — d) mixed-age group (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Weissman et al., 1997; Morphy et al., 2007; Neckelmann et al., 2007). Additionally, Roberts et al. (Roberts et al., 2000) were also considered in the mixed-age group as participants were aged 50 or older, thus, the sample included both working-age individuals and elderly. Only in one study, all participants were male (Chang et al., 1997), while in all other studies, the mean of the percentage of females was 55% (sd = 4.5), percentages ranging from 46% (38) to 62% (33). Four studies focussed on clinical samples. Hein et al. (2003) recruited participants with a positive family history of depression, Brabbins et al.(1993) and Perlis et al. (2006) recruited patients of general practitioners, and Roberts et al. (2002) recruited adolescents in managed care and use of services for both psychiatric and somatic complaints. All other studies focussed on the general population. All studies assessed insomnia and depression through subjective self-report, but one additionally measured Fig. 1. The search flow: results of search for articles. 2006 2007 2007 2008 2008 2008 Perlis et al. Morphy et al. Neckelmann et al. Buysse et al. Cho et al. Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom Roane and Taylor Kim et al. Szklo-Coxe et al. dur dur dur dur and and and and day day day day sd and dur sd, dur and day sd sd sd sd, sd, sd, sd, sd, dur and day sd and dur sd and dur sd and dur sd sd and dur sd sd and dur sd sd sd, dur and day sd In-home interview Geriatric Mental State Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale SCID and HAMD HADS HADS SPIKE SCID and BDI HADS 78 24 44 12 12 132 240 24 12 Diagnostic Interview Schedule 12 Psychiatric interview 84 Geriatric Mental State 36 NIHM Diagnostic Interview Schedule 42 Checklists. medical reports and self-reports 408 Diagnostic Interview Schedule 12 CES-D 36 CBCL and TRF 60 HADS 144 12 Items from the DSM-12D 12 Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children 12 Composite International Diagnostic Interview 60 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 3 1 1 2 1 1 7 1 3 1 1 1 1 1 7954 457 701 979 941 7113 6899 717 1244 2370 3136 664 N (t1) 45.79 21.00 69.76 26.14 26.00 48.23 80.09 6.00 55.00 64.90 15.00 60.00 4494 1204 1533 OR (95% CI) 3582 16.00 c&a 909 72.20 elderly 555 53.60 working [1.30–36.09] [1.37–5.37] [0.80–1.60] [1.10–2.10] [1.07–8.75] [2.11–5.83] 2.20 [1.34–3.58] 2.10 [1.50–3.00] 2.49 [0.83–7.50] 6.86 2.71 1.10 1.60 3.05 3.51 mixed 39.80 [19.8–80.00] working 2.16 [1.17–3.99] elderly 1.39 [1.07–1.79] working 2.10 [1.10–4.00] working 1.90 [1.20–3.20] mixed 5.40 [2.60–11.30] elderly 1.70 [1.29–2.23] c&a 1.53 [0.35–6.54] working 2.78 [1.59–4.90] mixed 4.85 [3.09–7.61] c&a 1.92 [1.30–1.92] elderly 2.40 [1.28–4.52] Mean Age age group 247 147 72.00 elderly 2363 1589 50.00 mixed 74,977 25,130 54.07 mixed 591 278 19.50 working 351 329 69.00 elderly 1812 1489 42.00 working 10,534 591 1070 1007 1053 18,571 9282 823 1870 2730 4175 775 FU in N of N (t0) months FU Abbreviations: NIHM: National Institute of Mental Health; CES-D: Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; TRF: Teacher Report Form; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DSM-12D: 12-item scale for DSM depression; HAMD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SPIKE: Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of Social Consequences of Psychic Disturbances for Epidemiology; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; PSG: polisomnographic assessment; sd: sleep difficulties criterion; dur: duration criterion; day: daytime consequences criterion; working: working-age group; elderly: elderly group; c&a: children and adolescents group; mixed: mixed-age group. 2008 2009 2010 1989 1989 1993 1996 1997 1997 1999 2000 2000 2000 2002 2003 Ford and Kamerow Vollrath et al. Brabbins et al. Breslau et al. Chang et al. Weissman et al. Foley et al. Johnson et al. Mallon et al. Roberts et al. Roberts et al. Hein et al. DSM-IV-TR insomnia Depression measures criteria satisfied 14 Diagnostic Interview Schedule Psychiatric interview Geriatric Mental State NIHM Diagnostic Interview Schedule Habit Survey Questionnaire Questionnaires Interview 1 item from the CBCL Uppsala Sleep Inventory 2 Items from the DSM-12D Questionnaires Composite International Diagnostic Interview HAMD (sleep items) Jenkins Sleep Scale Questionnaires SPIKE and visual analogue scales PSQI Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaires and Uppsala Sleep Inventory In-home interview Interview PSG + interview and self-reported symptoms PublYear Insomnia measures Authors Table 1 Study characteristics. Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 insomnia through polysomnographic assessment (SzkloCoxe et al., 2010). On average, the follow-up assessment was conducted after 71 months (sd = 96.0), ranging from 12 months to 408 months. Classifying the studies on the basis of the median value, 11 studies conducted the follow-up assessment after 1 to 3 years (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Brabbins et al., 1993; Weissman et al., 1997; Foley et al., 1999b; Roberts et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2002; Perlis et al., 2006; Morphy et al., 2007; Morphy et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2008; Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom, 2008; Kim et al., 2009), while 10 studies conducted the follow-up assessment after more than 3 years (Vollrath et al., 1989; Breslau et al., 1996; Chang et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2000; Mallon et al., 2000; Hein et al., 2003; Neckelmann et al., 2007; Buysse et al., 2008; Roane and Taylor, 2008; Szklo-Coxe et al., 2010). Five studies reported more than 1 follow-up assessment (Vollrath et al., 1989; Chang et al., 1997; Foley et al., 1999b; Buysse et al., 2008; Cho et al., 2008). All other studies reported only one follow-up assessment. Seven studies diagnosed insomnia on the basis of all DSM-IV criteria: sleep difficulties, duration and daytime consequences (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Roberts et al., 2002; Neckelmann et al., 2007; Buysse et al., 2008; Cho et al., 2008; Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom, 2008; Kim et al., 2009). Six studies took into consideration only sleep difficulties and duration criteria (Vollrath et al., 1989; Brabbins et al., 1993; Breslau et al., 1996; Weissman et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2000; Roane and Taylor, 2008), and eight studies based the diagnosis only on the sleep difficulties criterion (Chang et al., 1997; Foley et al., 1999b; Mallon et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2000; Hein et al., 2003; Perlis et al., 2006; Morphy et al., 2007; Szklo-Coxe et al., 2010). With respect to the publication year (median value), ten studies were published before 2001 (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Vollrath et al., 1989; Brabbins et al., 1993; Breslau et al., 1996; Chang et al., 1997; Weissman et al., 1997; Foley et al., 1999b; Mallon et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2000), while the other 11 studies were published after 2001. 3.1. Total sample The fixed-effects meta-analytic model (2.07; CI: 1.87– 2.29) and the random-effects meta-analytic model (2.60; CI: 1.98–3.42) were not concordant. The test for heterogeneity showed a significant index (Q-value = 124.7; df(Q) = 20; p b 0.001; and I2 = 83.96). The between-studies variance was τ 2 = 0.30 (standard error = 0.14; variance = 0.02; and τ = 0.55). The weights and the standardized residuals for each study are reported in Table 2. Due to the presence of heterogeneity, the random-effects meta-analytic model was selected (z = 6.85; N = 21, and p b 0.001). 15 Table 2 Weights and standardized residuals for each study. Study Weights (fixed) Standardized residuals (fixed) Ford and Kamerow 1989 Vollrath et al. 1989 Brabbins et al. 1993 Breslau et al. 1996 Chang et al. 1997 Weissman et al. 1997 Foley et al. 1999 Johnson et al. 2000 Mallon et al. 2000 Roberts et al. 2000 Roberts et al. 2002 Hein et al. 2003 Perlis et al. 2006 Morphy et al. 2007 Neckelmann et al. 2007 Buysse et al. 2008 Cho et al. 2008 Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom 2008 Roane and Taylor, 2008 Kim et al. 2009 Szklo-Coxe et al. 2010 2.10 2.72 15.45 2.45 4.25 1.89 13.65 0.48 3.25 5.03 6.82 2.57 0.37 2.19 8.51 9.78 0.93 3.96 4.24 8.51 0.84 8.39 0.14 − 3.30 0.04 − 0.35 2.58 − 1.52 − 0.41 1.05 3.80 − 0.40 0.46 1.42 0.78 − 3.74 − 1.65 0.73 2.08 0.25 0.08 0.33 p b 0.22; and I2 = 20.30). The fixed-effects meta-analytic model showed an overall odds ratio of 2.10 (CI: 1.86–2.38; z = 11.96; N = 17, p b 0.001). This show that non-depressed people with insomnia have a twofold risk to develop depression, compared to people with no sleep difficulties. The forest plot of these 17 studies is shown in Fig. 2. 3.3. Subgroup analysis: age groups Results showed that the working age group was not heterogeneous (Q-value = 7.8; df(Q) = 5; p = 0.2; and I2 = 35.7). The group of elderly was marginally heterogeneous (Q-value= 8.8; df(Q) = 5; p = 0.1; and I2 = 43.1). However, when excluding the studies with clinical samples (Perlis et al., 2006; Hein et al., 2003; Brabbins et al., 1993), which were conducted on samples of elderly participants, the elderly group was not anymore heterogeneous (Q-value = 1.7; df(Q) = 2; p = 0.4; and I2 = 0.0). The group of children and adolescents was also not heterogeneous (Q-value= 0.3; df(Q) = 2; p = 0.9; and I2 = 0.0). On the other hand, the mixed age group was heterogeneous. Considering the working age group, the fixed-effects model showed an odds ratio value of 2.1 (CI: 1.7–2.6; z = 7.4, N = 6, and p b 0.001). Considering the elderly group, without the three studies conducted on clinical samples, the fixed-effects model showed an odds ratio value of 1.9 (CI: 1.6–2.3; z = 5.9, N = 4, and p b 0.001). With respect to the group of children and adolescents, the fixed-effects model showed an odds ratio value of 2.0 (CI: 1.5–2.7; z = 4.6; N = 3; and p b 0.001). 3.2. Sensitivity analysis: excluding outliers 3.4. Publication bias Two studies had standardized residuals greater than +3LW43,46, and two studies had standardized residuals lower than −3LW39,27. The exclusion of these 4 studies explained most of the heterogeneity among the studies. The remaining studies, thus, were not heterogeneous (Q-value = 20.08; df(Q) = 16; The funnel plot was asymmetric with results in the same direction for most outcomes. However, the computation of the revisited file-drawer test for meta-analysis showed that the fail safe number (significance level: 0.05) of studies Author's personal copy 16 C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 Fig. 2. Meta-analysis of the effects of insomnia for future depression after exclusion of the outliers (fixed-effects meta-analytic model). necessary to “nullify” the average effect was n = 1782. Thus, the fail-safe number was immensely larger than the number of original studies (n = 21). 3.5. Incidence of depression Of the 21 studies considered, 6 reported the information about the number of individuals with insomnia (and no depression) at baseline who developed depression at followup and the number of those with no sleep difficulties (and no depression) at baseline who developed depression at followup (Szklo-Coxe et al., 2010; Morphy et al., 2007; Perlis et al., 2006; Chang et al., 1997; Weissman et al., 1997; Vollrath et al., 1989). Considering these studies together, within a total of 797 individuals with insomnia at baseline, 90 developed new depression at follow-up (incidence in percentage: 11.3). Within a total of 6919 individuals with no sleep difficulties at baseline, 168 developed new depression at follow-up (incidence in percentage: 2.4). Three more studies reported the incidence of depression in percentage respectively for both the group with and without insomnia at baseline (Roane and Taylor, 2008: 22.9 and 10.2; Breslau et al., 1996: 15.9 and 4.6; Ford and Kamerow, 1989: 22.9 and 10.2). Calculating a mean incidence in percent considering these 9 studies together, we found that in the group of those with insomnia at baseline, the incidence value is 13.1, while in the group of those without sleep difficulties at baseline, the incidence value is 4.0. 4. Discussion The results of the present analysis indicate that nondepressed subjects with insomnia have a twofold risk to develop depression, compared to people with no sleep difficulties. The pooled estimates were high despite the wide variability in study populations, design and measures, and persisted to be high after exclusion of the outliers (OR = 2.10; 95%; and CI: 1.86–2.38). More specifically, the incidence of depression in the group with insomnia (and no depression) at baseline was significantly higher (incidence in percentage: 13.1) than the incidence of depression in the group without sleep difficulties (and no depression) at baseline (incidence in percentage: 4.0). The incidence in percentage of depression in the general population has been reported to be 9.9 (Murphy et al., 2002). That is, in a specific group with sleep difficulties, the incidence of depression is higher in comparison to the general population. It is also interesting to notice that in a specific group of people with no sleep difficulties, the incidence of depression is much lower as compared to the general population. Subgroup analysis considering the different age-groups showed that the effect of insomnia in predicting subsequent depression is similar in children and adolescents, workingage individuals, and elderly individuals. Our analysis is the first attempt to quantitatively summarize the results of longitudinal studies on the role of insomnia as a predictor of depression. Insomnia is one of the most common health problems in industrialized countries, affecting approximately 10% of the general population in its chronic form and about 30% occasionally (Ohayon, 2009). The understanding of the role of sleep in depression has been suggested to yield important insights into the pathophysiology of the disorder (Murray and Lopez, 1996). Based on this, the results of the present analysis indicate important research and clinical implications. Psychophysiological mechanisms through which insomnia predicts depression are still not clear. Recent interest has been dedicated to the role of insomnia in emotion regulation, which might explain why insomnia leads to depression (Koffel and Watson, 2009; Baglioni et al., 2010a). From a neurobiological perspective, a Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 dysfunction in sleep-wake regulating neural circuitries may lead to alterations in emotional reactivity (Riemann et al., 2010). Moreover, emotional stimuli interact with the basic homeostatic and circadian drives for sleep through the interaction of affect-related and sleep-related brain regions (Saper et al., 2005). A few studies have found altered emotional responses in people with insomnia as compared to good sleepers, both using subjective (Scott and Judge, 2006) and objective measures (Baglioni et al., 2010b). However, further investigation is needed, especially with regard to the role of age and gender. With respect to clinical implications, treating insomnia in its early stage might be effective in ameliorating sleep quality and in preventing mood dysfunctions (Riemann, 2009; Baglioni et al., 2010a). However, although cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is known to be effective and exerts stable long-term results (Riemann and Perlis, 2009) only a minority of afflicted individuals are treated in this way because its implementation is presently mostly restricted to academic and research contexts. Dissemination of CBT-I protocols, for example through general practitioners, might lead to better results. Easy accessible intervention programs for insomnia for the general population could be a very important goal for the next years as a preventive strategy for depression. The quality of the original studies was appraised through the consideration of mean sample size and length of followup periods, as well as the evaluation of the definition of insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR criteria. As a whole, the studies included in this meta-analysis reported data from a large number of individuals taken mostly from the general population in different countries (USA, UK, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Norway, and South Korea). Additionally, a great number of these studies followed the participants for more than 3 years. That is, symptoms of insomnia may have existed already many years before the onset of a depressive episode. Three of the 17 selected studies, after exclusion of outliers, applied the follow-up assessment after more than 10 years (Chang et al., 1997; Mallon et al., 2000; Buysse et al., 2008). As the prodromal period of a first episode of major depression may be up to 8–10 years (Dryman and Eaton, 1991), these 3 studies suggest that insomnia could be not only a prodrome of, but also an independent risk factor of depression, at least in the 18–60 years old group. However, it could also be argued that insomnia represents the first clinical sign of depression. In order to deepen this issue, further investigations should focus on possible neurobiological links between insomnia and depression. Moreover, prospective intervention studies focussing on insomnia in different age-samples should be conducted in order to assess the expected decrease of the incidence of depression. Finally, it is noteworthy that of the 10 studies published before 2001, only one defined insomnia on the basis of sleep difficulties, duration and daytime consequences, whereas, of the 11 studies published after 2001, 7 studies did so. This reflects the changes in the conceptualization of insomnia in the last 20 years. The four outlier studies (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Brabbins et al., 1993; Roberts et al., 2000; Neckelmann et al., 2007) did not included smaller sample sizes, or shorter length of follow-up periods, or satisfied less the DSM-IV-TR 17 criteria for insomnia, compared to the other studies. As 3 of them recruited both working-age participants and elderly (Ford and Kamerow, 1989; Roberts et al., 2000; Neckelmann et al., 2007), it might be argued that studies with mixed-age samples could have required the use of several different sites for recruitment and this might have influenced the carefulness of the selection. However, other two studies did so and did not belong to the outlier group (Weissman et al., 1997; Morphy et al., 2007). Anyway, the effects reported in the 4 outlier studies were in the same direction of the pooled estimate of the effect resulting from the remaining 17 studies. Quantitative reviews, as meta-analysis, have the potential to be affected by publication bias. However, our analysis indicates that a publication bias was not the source of the overall results of our meta-analysis, as the “fail safe number” was much larger than the number of the original studies. Some limitations of the current analysis have to be addressed. First, results cannot be generalized with respect to gender. The majority of the included studies reported a summarized odds ratio for both women and men. Additionally, as studies differed with respect to the definition of insomnia, it is impossible to evaluate whether clinical symptoms of insomnia might have a greater impact in predicting depression or not as compared to the experience of poor sleep. Further, insomnia is a heterogeneous disorder including different problems related to poor sleep and its consequences. As the definition of insomnia considered in the selected studies, independently on how accurate it was, referred to a representative heterogeneous sample of people with sleep difficulties, it would be interesting to conduct longitudinal studies on the causal relationship between insomnia and depression taking into account insomnia subtypes. Moreover, there is a need for future research to evaluate the predictor role of insomnia for depression, rigorously independently from all other related variables, as alcohol or drug abuse, other somatic or psychiatric diseases, and/or medication status. Additionally, studies on children and adolescents are still too few and the issue needs further investigation. These studies appear of great interest, as interventions in early periods of life could lead to significant benefits for the individual and improve public health outcomes. The link between insomnia and mood regulation is consistent with the clinical evidence that insomnia commonly co-occurs with all most relevant and frequent psychiatric conditions. The transdiagnostic nature of insomnia with respect to psychiatric disorders (Harvey, 2009) suggests that future research strategies in insomnia address neurobiological underpinnings in relation to other mental disorders and clarify a possible preventive role of insomnia treatment in general for mental health. Role of funding source Dr. Baglioni and Prof. Dr. Riemann have received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (People, Marie Curie Actions, Intra-European Fellowship, FP7-PEOPLE-IEF-2008) under grant agreement n. 235321 and from OPTIMI (FP7-JCT-2009-4; 248544) for this work. The sources of funding had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Conflict of interest The corresponding author, Dr. Baglioni, confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Author's personal copy 18 C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 Dr. Nissen has received speaker honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis and Lundbeck. Dr. Voderholzer has received speaker honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Cephalon, and Lilly. He has been principal investigator of an investigator initiated trial sponsored by Lundbeck. Dr. Riemann received research support from Takeda, Sanofi-Aventis, Organon, Actelion and Omron. He was on the speaker's bureau of Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, Servier, Lundbeck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GSK, Cephalon and Merz Pharmaceuticals. He was also a member of advisory boards for Sanofi-Aventis, Lundbeck, GSK, Takeda and Actelion. Dr. Nissen, Dr. Voderholzer, and Dr. Riemann declare that the above mentioned activities have no influence on the content of this article. All the other authors reported no conflicts of interest. References Baglioni, C., Lombardo, C., Bux, E., Hansen, S., Salveta, C., Biello, S., Violani, C., Espie, C.A., 2010a. Psychophysiological reactivity to sleep-related emotional stimuli in primary insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther. 48 (6), 467–475. Baglioni, C., Spiegelhalder, K., Lombardo, C., Riemann, D., 2010b. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Med. Rev. 14 (4), 227–238. Barkow, K., Heun, R., Üstün, T.B., Maier, W., 2001. Identification of items which predict later development of depression in primary health care. Eur. Arch. Psy. Clin. N. 251 (Suppl 2), II/21–II/26. Berger, A.K., Small, B.J., Forsell, Y., Winblad, B., Bäckman, L., 1998. Preclinical symptoms of major depression in very old age: a prospective longitudinal study. Am. J. Psychiat. 155 (8), 1039–1043. Borenstein, M., Hedges, L.V., Higgins, J.P.T., Rothstein, H.R., 2006. Comprehensive Meta-analysis (Version 2.2.027) [Computer software]. Biostat, Englewood, NJ. Borenstein, M., Hedges, L.V., Higgins, J.P.T., Rothstein, H.R., 2009. Introduction to Meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK. Brabbins, C.J., Dewey, M.E., Copeland, J.R.M., Davidson, I.A., McWilliam, C., Saunders, P., Sharma, V.K., Sullivan, C., 1993. Insomnia in the elderly: prevalence, gender differences and relationships with morbidity and mortality. Int. J. Geriatr. Psych. 8 (6), 473–480. Breslau, N., Roth, T., Rosenthal, L., Andreski, P., 1996. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol. Psychiat. 39 (6), 411–418. Buysse, D.J., Angst, J., Gamma, A., Ajdacic, V., Eich, D., Rössler, W., 2008. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep 31 (4), 473–480. Chang, P.P., Ford, D.E., Mead, L.A., Cooper-Patrick, L., Klag, M.J., 1997. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 146 (2), 105–114. Cho, H.J., Lavretsky, H., Olmstead, R., Levin, M.J., Oxman, M.N., Irwin, M.R., 2008. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am. J. Psychiat. 165 (12), 1543–1550. Cukrowicz, K.C., Otamendi, A., Pinto, J.V., Bernert, A., Krakow, B., Joiner Jr., T.E., 2006. The impact of insomnia and sleep disturbances on depression and suicidality. Dreaming 16 (1), 1–10. Dryman, A., Eaton, W.W., 1991. Affective symptoms associated with the onset of major depression in the community: findings from the US National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiat. Scand. 84 (1), 1–5. Foley, D.J., Monjan, A., Simonsick, E.M., Wallace, R.B., Blazer, D.G., 1999a. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6, 800 persons over three years. Sleep 22 (Suppl 2), S366–S372. Foley, D.J., Monjan, A.A., Izmirlian, G., Hays, J.C., Blazer, D.G., 1999b. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults in a biracial cohort. Sleep 22 (Suppl 2), S373–S378. Ford, D.E., Kamerow, D.B., 1989. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? JAMA 262 (11), 1479–1484. Green, B.H., Copeland, J.R., Dewey, M.E., Sharma, V., Saunders, P.A., Davidson, I.A., Sullivan, C., McWilliam, C., 1992. Risk factors for depression in elderly people: a prospective study. Acta Psychiat. Scand. 86 (3), 213–217. Gregory, A.M., O'Connor, T.G., 2002. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioural problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy. 41 (8), 964–971. Gregory, A.M., Caspi, A., Eley, T.C., Moffitt, T.E., O'Connor, T.G., Poulton, R., 2005. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. J. Abnorm. Child. Psych. 33 (2), 157–163. Gregory, A.M., Van der Ende, J., Willis, T.A., Verhulst, F.C., 2008. Parentreported sleep problems during development predict self-reported anxiety/depression, attention problems and aggressive behavior later in life. Arch. Pediatr. Adol. Med. 162 (4), 330–335. Gregory, A.M., Rijsdijk, F.V., Lau, J.Y., Dahl, R.E., Eley, T.C., 2009. The direction of longitudinal associations between sleep problems and depression symptoms: a study of twins aged 8 and 10 years. Sleep 32 (2), 189–199. Harlow, S.D., Goldberg, E.L., Comstock, G.W., 1991. A longitudinal study of risk factors for depressive symptomatology in elderly widowed and married women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 134 (5), 526–538. Harvey, A.G., 2009. A transdiagnostic approach to treating sleep disturbance in psychiatric disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 38 (S1), 35–42. Hedges, L.V., Olkin, I., 1985. Diagnostic procedures for research synthesis models. Statistic Methods for Meta-analysis. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. Hein, S., Bonsignore, M., Barkow, S., Jessen, F., Ptok, U., Heun, R., 2003. Lifetime depressive and somatic symptoms as preclinical markers of late-onset depression. Eur. Arch. Psy. Clin. N. 253 (1), 16–21. Higgins, J.P.T., Thompson, S.G., 2002. Quantifying heterogeneity in metaanalysis. Stat. Med. 21 (11), 1539–1558. Hirschfeld, R.M., Keller, M.B., Panico, S., Arons, B.S., Barlow, D., Davidoff, F., Endicott, J., Froom, J., Goldstein, M., Gorman, J.M., Marek, R.G., Maurer, T.A., Meyer, R., Phillips, K., Ross, J., Schwenk, T.L., Sharfstein, S.S., Thase, M.E., Wyatt, R.J., 1997. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277 (4), 333–340. Hohagen, F., Rink, K., Käppler, C., Schramm, E., Riemann, D., Weyerer, S., Berger, M., 1993. Prevalence and treatment of insomnia in general practice. A longitudinal study. Eur. Arch. Psy. Clin. N. 242 (6), 329–336. Hohagen, F., Käppler, C., Schramm, E., Riemann, D., Weyerer, S., Berger, M., 1994. Sleep onset insomnia, sleep maintaining insomnia and insomnia with early morning awakening — temporal stability of subtypes in a longitudinal study on general practice attenders. Sleep 17 (6), 551–554. Jansson, M., Linton, S.J., 2006. The role of anxiety and depression in the development of insomnia: cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Psychol. Health 21 (3), 383–397. Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Lindblom, K., 2008. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J. Psychosom. Res. 64 (49), 443–449. Johnson, E.O., Chilcoat, H.D., Breslau, N., 2000. Trouble sleeping and anxiety/ depression in childhood. Psychiat. Res. 94 (2), 93–102. Kennedy, G.J., Kelman, H.R., Thomas, C., 1990. The emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disability. J. Commun. Health 15 (2), 93–104. Kim, J.M., Stewart, R., Kim, S.W., Yang, S.J., Shin, I.S., Yoon, J.S., 2009. Insomnia, depression, and physical disorders in late life: a 2-year longitudinal community study in Koreans. Sleep 32 (9), 1221–1228. Koffel, E., Watson, D., 2009. The two-factor structure of sleep complaints and its relation to depression and anxiety. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118 (1), 183–194. Kraepelin, E., 1909. Psychiatrie. JA Barth, Leipzig. Liberati, A., Altman, D.G., Tetzlaff, J., Murlow, C., Gøtzsche, P.C., Ioannidis, J.P.A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P.J., Kleijnen, J., Moher, D., 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Brit. Med. J. 339, b2700. Lichstein, K.L., 2006. Secondary insomnia: a myth dismissed. Sleep Med. Rev. 10 (1), 3–5. Livingston, G., Blizard, B., Mann, A., 1993. Does sleep disturbance predict depression in elderly people? A study in inner London. Brit. J. Gen. Pract. 43 (376), 445–448. Livingston, G., Watkin, V., Milne, B., Manela, M.V., Katona, C., 2000. Who becomes depressed? The Islington community study of older people. J. Affect. Disorders 58 (2), 125–133. Lopez, A.D., Mathers, C.D., Ezzati, M., Jamison, D.T., Murray, C.J., 2006. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods, and results for 2001. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Worldbank and Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 85–86. Mallon, L., Broman, J.E., Hetta, J., 2000. Relationship between insomnia, depression, and mortality: a 12-year follow-up of older adults in the community. Int. Psychogeriatr. 12 (3), 295–306. Manber, R., Edinger, J.D., Gress, J.L., San Pedro-Salcedo, M.G., Kuo, T.F., Kalista, T., 2008. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep 31 (4), 489–495. McCrae, C.S., Lichstein, K.L., 2001. Secondary insomnia: diagnostic challenges and intervention opportunities. Sleep Med. Rev. 5 (1), 47–61. Moore, M., Yuen, H.M., Dunn, N., Mullee, M.A., Maskell, J., Kendrick, T., 2009. Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a descriptive study using the general practice research database. Brit. Med. J. 339, b3999. Morgan, K., Healey, D.W., Healey, P.J., 1989. Factors influencing persistent subjective insomnia in old age: a follow-up study of good and poor sleepers aged 65–74. Age Ageing 18 (2), 117–122. Author's personal copy C. Baglioni et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 135 (2011) 10–19 Morphy, H., Dunn, K.M., Lewis, M., Boardman, H.F., Croft, P.R., 2007. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep 30 (3), 274–280. Murphy, J.M., Nierenberg, A.A., Laird, N.M., Monson, R.R., Sobol, A.M., Leighton, A.H., 2002. Incidence of major depression: prediction from subthreshold categories in the Stirling County Study. J. Affect. Disorders 68 (2–3), 251–259. Murray, C.J.L., Lopez, A.D., 1996. The Global Burden of Disease. World Health Organization and Harvard University Press, Boston. Neckelmann, D., Mykletun, A., Dahl, A.A., 2007. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep 30 (7), 873–880. NIH, 2005. National institutes of health state of the science conference statement. Manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Sleep 28 (13–15), 1049–1057. Ohayon, M.M., 2009. Difficulty in resuming or inability to resume sleep and the links to daytime impairment: definition, prevalence and comorbidity. J. Psychiat. Res. 43 (10), 934–940. Ong, S.H., Wickramaratne, P., Tang, M., Weissman, M.M., 2006. Early childhood sleep and eating problems as predictors of adolescent and adult mood and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disorders 96 (1–2), 1–8. Paffenbarger Jr., R.S., Lee, I.M., Leung, R., 1994. Physical activity and personal characteristics associated with depression and suicide in American college men. Acta Psychiat. Scand. 89 (s377), 16–22. Patten, C.A., Choi, W.S., Gillin, J.C., Pierce, J.P., 2000. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics 106 (2), E23. Perlis, M.L., Smith, L.J., Lyness, J.M., Matteson, S.R., Pigeon, W.R., Jungquist, C.R., Tu, X., 2006. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in elderly. Behav. Sleep Med. 4 (2), 104–113. Pigeon, W.R., Hegel, M., Unützer, J., Fan, M.Y., Sateia, M.J., Lyness, J.M., Phillips, C., Perlis, M.L., 2008. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for latelife depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep 31 (4), 481–488. Prince, M.J., Harwood, R.H., Thomas, A., Mann, A.H., 1998. A prospective population-based cohort study of the effects of disablement and social milieu on the onset and maintenance of late-life depression. The Gospel Oak Project VII. Psychol. Med. 28 (2), 337–350. Reynolds, C.F., Redline, S., 2010. DSM-V sleep–wake disorders workgroup and advisors. The DSM-V sleep–wake disorders nosology: an update and an invitation to the sleep community. Sleep 33 (1), 10–11. Riemann, D., 2009. Does effective management of sleep disorders reduce depressive symptoms and the risk of depression? Drugs 69 (Suppl 2), 43–64. Riemann, D., Perlis, M.L., 2009. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioural therapies. Sleep Med. Rev. 13 (3), 205–214. Riemann, D., Voderholzer, U., 2003. Primary Insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J. Affect. Disorders 76 (1–3), 255–259. 19 Riemann, D., Berger, M., Voderholzer, U., 2001. Sleep in depression: results from psychobiological studies. Biol. Psychol. 57 (1–3), 67–103. Riemann, D., Spiegelhalder, K., Feige, B., Voderholzer, U., Berger, M., Perlis, M., Nissen, C., 2010. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 14 (1), 19–31. Roane, B.M., Taylor, D.J., 2008. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep 31 (10), 1351–1356. Roberts, R.E., Shema, S.J., Kaplan, G.A., Strawbridge, W.J., 2000. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: a prospective perspective. Am. J. Psychiat. 157 (1), 81–88. Roberts, R.E., Robert, C.R., Chen, I.G., 2002. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J. Psychosom. Res. 53 (1), 561–569. Rodin, J., McAvay, G., Timko, C., 1988. A longitudinal study of depressed mood and sleep disturbances in elderly adults. J. Gerontol. 43 (2), 45–53. Rosenberg, M.S., 2005. The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution 59 (2), 464–468. Saper, C.B., Cano, G., Scammell, T.E., 2005. Homeostatic, circadian, and emotional regulation of sleep. J. Comp. Neurol. 493 (1), 92–98. Schramm, E., Hohagen, F., Käppler, C., Grasshoff, U., Berger, M., 1995. Mental comorbidity of chronic insomnia in general practice attenders using DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiat. Scand. 91 (1), 10–17. Scott, B.A., Judge, T.A., 2006. Insomnia, emotions and job satisfaction: a multilevel study. J. Manage 32 (5), 622–645. Staner, L., 2010. Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med. Rev. 14 (1), 35–46. Stroup, D.F., Berlin, J.A., Morton, S.C., Olkin, I., Williamson, G.D., Rennie, D., Moher, D., Becker, B.J., Sipe, T.A., Thacker, S.B., 2000. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 (15), 2008–2012. Szklo-Coxe, M., Young, T., Peppard, P.E., Finn, L.A., Benca, R.M., 2010. Prospective associations of insomnia markers and symptoms with depression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 171 (6), 709–720. Taylor, D.J., Lichstein, K.L., Weinstock, J., Sanford, S., Temple, J.R., 2007. A pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy of insomnia in people with mild depression. Behav. Ther. 38 (1), 49–57. Tsuno, N., Besset, A., Ritchie, K., 2005. Sleep and depression. J. Clin. Psychiat. 66 (10), 1254–1269. Vollrath, M., Wicki, W., Angst, J., 1989. The Zurich study. VIII. Insomnia: association with depression, anxiety, somatic syndromes, and course of insomnia. Eur. Arch. Psy. Clin. N. 239 (2), 113–124. Weissman, M.M., Greenwald, S., Niño-Murcia, G., Dement, W.C., 1997. The morbidity of insomnia uncomplicated by psychiatric disorders. Gen. Hosp. Psychiat. 19 (4), 245–250. Winokur, G., Clayton, P.J., Reich, T., 1969. Manic Depressive Illness. Mosby, St Louis, MO.