Inflammation, Sleep, Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease M.A. Miller* and F.P. Cappuccio

advertisement

Carrmt Vascular Pharmacologlt, 2007, t 000-000

Inflammation, Sleep,Obesity and CardiovascularDisease

M.A. Miller* andF.P.Cappuccio

Clinical SciencesResearch Institute, Ilarwick Medical School, Coventry, UK

Abstract: Evidenceis emergingthat disturbancesin sleepand sleepdisordersplay a role in the morbidity of chronicconditions. However, the relationshipbetweensleepprocesses,diseasedevelopment,diseaseprogressionand diseasemanagementis often unclearor understudied.

Numerouscommon medical conditionscan have an affect on sleep.For example,diabetesor inflammatory conditions

such as arthritis can lead to poor sleepquality and induce symptomsofexcessive daytime sleepinessand fatigue.It has

also beensuggestedthat poor sleepmay lead to the developmentof cardiovasculardiseasefor which an underlying inflammatorycomponenthas beenproposed.It is thereforeimportantthat the developmentand progressionofsuch disease

statesare studiedto determinewhetherthe sleepeffect merely reflectsdiseaseprogressionor whetherit may be in some

way causallyrelated.Sleeploss can alsohave consequences

on safetyrelatedbehavioursboth for the individualsand for

the society,for examplethe increasedrisk of accidentswhen driving while drowsy. Sleepis a complexphenotypeand as

such it is possiblethat there are numerousgeneswhich may eachhave a number of effects that control an individual's

sleeppattern.

This review examinesthe interactionbetweensleep(both quantityand quality) and parametersof cardiovascularrisk. We

alsoexplorethe hypothesisthat inflammationplays an essentialrole in cardiovasculardiseaseand that a lack ofsleep mav

play a key role in this inflammatoryprocess.

Aim: To review currentevidenceregardingthe endocrine,metabolic,cardiovascularand immune functionsand their interactionswith regardto sleep,given the currentevidencethat sleepdisturbances

may affect eachofthese areas.

Keywords: Sleep, obesity, cardiovasculm disease,inflammation, innate immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Sleepis a natural processand yet the exact purposeof

sleepand its effect on healthand diseaseremainsto be fully

elucidated.Both physiologicaland pathologicalsleep is divided into two states: non-rapid-eye-movement(NREM)

sleepand rapid-eyemovement(REM) sleep[]. It has been

suggestedthat it is crucial for the maintenanceand restoration of homeostasis

throughthe regulationof energy,repair

and infectioncontrol and that it may be importantin the programmingof thebrain[l-3]. It is now particularlyrelevantto

understand

the importanceof sleep,as sleepinghabitswithin

our societyhave been changingover a period of yearsas a

resultofdecreaseddependencyon day light hours,increased

shift-work and changesin lifestyle and home environments

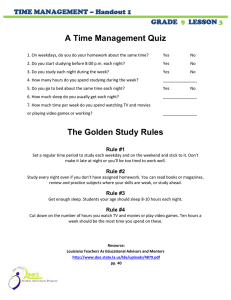

[4, 5]. Statistics from the National Sleep Foundation in

America suggestthat approximatelyone-thirdof Americans

sleep6.5 h a nightor lessFig. (l) t5l.

It is well establishedthat sleep disorderssuch as sleep

apnoeacan lead to serioushealthproblemsincluding cardiovasculardisease[6-9]. New datasuggeststhat 'healthy' individualswho do not get enoughsleepmight be at risk of poor

healthin the future [0, 1l]. Moreover,there is increasing

evidenceto suggestthat sleepdisturbancesmay be an impor*Address correspondence

to this author at the Clinical SciencesResearch

Institute, Clinical SciencesBuilding-UHCW Campus, Warwick Medical

School, Clifford Bridge Road, Coventry, Cyz 2DX, UK; Tel: 024 7696

8666;Fax: 024 7696 8660; E-mail: Michelle.Miller@warwick.ac.uk

ts70-t6tt t07$50.00+.00

l*vr:*

**$,

parng{

lAl

EA

;"fi

ti6

n*

'tr*

,&t

,*i

,&I

:,8*

:tfi

n*

Fig. (1).Durationof sleepin theaverage

US population

in thelast

century

tant determinantof diseaseand morbidity andthat inflammatory processes

may play an importantrole [2, 3, 12, l3]. A

decreasein sleepleadsto an increasein inflammatorycytokines which are now believedto be importantin the developmentofcardiovascular

risk progression

[2]. Indeed,there

is an increasedrisk of heart attacksand strokesduring the

early morning and it is possiblethat sleephas an effect on

the endothelialfunction of blood vessels[14]. This review

focuseson risk factors for diabetesand cardiovasculardiseaseandtheir relationshipto sleepand inflammation.

Cardiovascular Disease,Sleepand Inflammation

Individuals who experiencesleep problems have been

shownto be at an increasedrisk ofcardiovascularevents[9],

@ 2007 Bentham SciencePublishers Ltd.

2

Current Vascular pharmacotogt, 2007, Vol S, No. 2

which is reducedfollowing successfultreatrnentwith Con_

tinuous.Positive,Airway pressure(CpAp), surgery (uvulo_

palatopharyngoplasty

(Uppp)) or oral applian.r'fr j]. Within

the.generalpopulation sleep complajnii are ur.y ,o*ron

and are often associatedwith midical, psychologicatand

socia-ldisturbances[16]. Inflammatory pror.rr., aie impor_

tant in the developmentand progresiion of cardiovascular

disease^and_it

is possiblethat disiurbancesin sleeppa$erns

may affecttheseprocessesFig. (2).

$laeplssr

I

,

Frs*inflam

matsry cy{akine*

I

,

I

f

Cardisva$sulsr

di*ease

Fig.(2).Sleeploss,inflammation

andcardiovascular

disease

Patientswith obstructivesleep apnea(OSA) syndrome

who have associatedcardiovasculaidiseasehave significantly elevatedC-reactiveprotein (CRp) comparedto ihose

yjth OSA syndrome but without cardiovasculardisease

(CVD) or thosewirhout OSA syndromeor CVD

[12].

Age,Sleepand Inflammation

Age is a risk factor for cardiovasculardiseaseand ageing

and is associated

with changesin length and quality ofiteei

as well as an increasein the prevalenceof sleepcomplainti

[I3]..S.leepproblemsincreas-e

with age and the deviloped

world.is experiencingan increasein its ageingpopulation.

'illnesses

I .ikewise,the numberof individualswittr ctrronic

is

increasing.It is therefore important that the bidirectional

effect of sleep on diseaseprogressionand developmentis

evaluated.Fufihermore,it has been demonstratedin young

adultsthatsleepdeprivationleadsto metabolic,systemicand

immunechangesthat are similar to thoseobservedin ageing

and age-relateddisorders [13]. However, although treitfri

elderlyadultsspendmore time in bed,they spendlesstime

asleepand are more easily arousedfrom sieepthan younger

individuals[17]. Ageing is associated

with an increasein

Sleep-Disordered

Breathing(SDB), daytimesleepiness

and

Miller and Cappaccio

insomniaas well as loud snoring,difficultiesmaintaining

s1eep,fatigue, mood effects and impairmentof daily activi

ties. These factors can lead to an increasein depression,

memoryproblems,a declinein cognitivefunctioningand

a

lowerqualityof life [18, t9,Z0l.

The_.ageingprocess is associatedwith changesin the

metabolicprocessand diseasedevelopmentand &idence is

accumulatingto suggestthat sleep_deprivation

is associated

with similar-changes.Furthermore,there is an increasin!

body of evidenceto suggestthat the ageingprocess,sleei

andthe inflammatoryprocesses

arerelaiedyZ.i_Z+1.It

is im'_

po.r?nttlat n9! only are sleep regulatorymechanismsstud_

ied but the effect of ageing on ihese processesare deter'boundaries

mined. A better understandingof the

between

normal and abnormalage-relatedchangesin sleepbehaviour

should allow the developmentof inierventionguidelines.

Moreover, the exact nature_of relationshipsanj causality

between sleep, age and inflammation remain to be eluci_

dated.Increasedlevelsof a numberof inflammatorymarkers

in elderly populationhave beenobserved,for exampleCRp

and interleukin-6 (IL-6) increasewith age

[Zt, iZ]. fur_

thermore,partial short term sleepdeprivatiin gives rise to a

similar pattem of CRp response[23]. Sleepieprivation is

also associatedwith an increased-geneexpiessibnof heat_

shockprotein[24l.It is thereforepoisiblethatsleepdeprivation may contribute to the increise systemic inflammation

observedin ageing.The exactprocesshoweverremainsto be

determinedbut may also involveoxidativestress

[25] or the

regufationof growth hormone 126l and its associitedeffect

on theimmunefunction.

Gender,Sleepand Inflammation

Men are at increasedrisk of CVD but it is not clear

whetherthis is associatedwith genderdifferencesin pattems

of sleep.It has also beensuggestedthat the menopausealso

may be a risk for sleep_disordered

breathing(SbB) t271.

Genderdifferencesin inflammatory markershave been ob_

served[28]. We have shownthat certainadhesionmolecule

levels are lower in women than in men

[2g]. Furthermore,it

is possiblethat the associationbetweeniteep anOcardiovas_

cular risk factors such as the Body-Mass_Index

(BMI) may

vary beh.veen

sexes,at leastin adolescents.

Knutsondemon_

stratedthat while short sleepmay have an effect on BMI in

young men this does not appearto be the case in young

women.[29].

Ethnicity, Sleepand Inflammation

SouthAsians have a higher risk of CVD than whites and

individuals of African origin appearto be protectedfrom

coronaryheartdisease(CHD) t301.

^ An increasedprevalenceof insomniahasbeenreportedin

Americanscomp_qgd

with whites,which may in part

,Africal

be attributableto ethnicdifferencesin associated

risk faclors,

:ulh-_3solgsity l3ll. Ir is not known whetherthis is preseni

in UK African individualswho have a much lower risk of

CHD than their American counterpaxts

[30]. It hasbeensug_

gestedthat there may be a genetic componentfor this increase[32] and it would thereforebe importantto studyboth

UK Africans and Africans in Africa. Diibetes and strokeare

high in UK Africans as well as African Americans.Ethnic

Intlammation, Sleep, ObesiE nnd Cardiovascular Disease

differencesin inflammatory markers have been observed

[28] which in part are associatedwith ethnic differencesin

cardiovascular

risk. It is importantthat future studiesinvestigatewhetherethnicdifferencesin CHD, diabetesand stroke

are in any way relatedto differencesin sleepdisordersand

whether or not there may be an underlying inflammatory

component.

Obesity,Sleepand Inflammation

Obesityis associatedwith an increasein SDB and OSA

(SAS) [33]. Obesityis becominga global epidemicin both

adultsand children and is associatedwith an increasedrisk

of morbidityandmortality as well as reducedlife expectancy

[341. It is clear that obesity may have its effect on CVD

through a number of different known and possibly as yet

Theseinclude dyslipidemia,hyperunknownmechanisms.

tension,glucoseintolerance,inflammation,OSAftrypoventilation, and the prothromboticstate [34]. Obesity leadsto a

changein an individual's metabolicprofile and an accumulation of adiposetissue.

Lack of sleepmay have an effect on the developmentof

obesity and subsequentCVD through a number of mecha-

Cunent VascularPharmacolog42007, VoI 5, No. 2

nisms.Spiegelet al, in the first randomizedcross-overclinical trial of short-term sleep deprivation,demonstratedthat

sleep deprivationwas associatedwith decreasedleptin and

ghrelinlevels[35]. This in turn wouldleadto a coincreased

comittantincreasein hunger and appetite,increasedinsulin

resistanceand accumulationof fat and decreasedcarbohydratemetabolismFig. (3). The individualsin this studywere

subjectedto extremeacutesleepdeprivation(<4 h per night)

and further studiesare requiredto determinethe effects on

thesehormonesof more modestsleepdeprivation(<5 h per

night),especiallyin the long-term[35]. A studyof422 children(boysand girls ofprimary schoolage(5-l0years))has

demonstratedan associationbetweensleepdurationand the

risk to developchildhood overweight/obesity [36]. Interestingly, the NursesHealth Study demonstrated

that while short

sleepdurationleadsto an increasein weight with time there

was no evidenceto suggestthat this was the result of an increasein appetite[37]. Thesefindings are in contrastto othersthat havedemonstrated

a clearrelationshipbetweenduration of sleep,ghrelin, leptin and appetite[35,38]. The findings from the NursesHealth Study suggestthat perhapsthe

effectsof sleepon obesity occur as a result of a changein

energy metabolism.Uncoupling proteins are proteins that

L&SKOT SLESF

HYFgTHiLfrII[US

-fitry*lxtlen w,fpfisfgf *lf$

f

*1'^1"1.^i

sro*ffi

""**-;;;

'iAFFeti*i-

" i Carfmydrate uttlbflnfin

.{ Fatutl[zatisn

i$ &a$tfisme{ility

'1&*ifi $*fr*:i{r}

"{.ts{8{ll€t$fg*erry

dffeste Bnsrgysfl endih.re

48{platFs aldocrine fLs'*ctio{t

,xri$nl*ta,]sli$rfl

nmut$rr

4rreutr*rs$tst*ltrs

iT**:AH**i

lc?g{,r}in

4**€s**e. *sllsrt

.t Uptakrofgluc{rse

,t Glycogen

deposlthn

in il.relhrer

'* Ghmose

rc{ease

hyr€ lider

.t F8tr tntake

"f trr!ryWWffiqndi*rr,s

Fig,(3).Effect ofthe lack ofsleep on energyregulatinghormones

3

4

Current Vascularpharmacolog,2007, VoL S, No.2

Miller and Cappuccio

uncoupleproton exchangeald ATp production. polymor_

phjc,variationin these.genes

hasbeenielatedto energyme_

tabo,llsm,

obesityand diabetes[39, 40]. Furthermore,

-irelli

et al demonstratedthat in animal studies,sleep

depiivation

was associatedwith an increasein Uncoupling protein

2

(UCP2) expressionin liver and skeletal .ir"iE

t4tl. Th;

latter is

_thelargest tissue in the body, -O t rn". and in_

UCP2 expressionin this tissue may have a poren_

.:T?":d

uauy targeettecton restingenergyexpenditure

[41].

Inflammatory processmay also underlie the elfect

.

of

sleepon w_eightgain. Recentitudies have shownthe importanceofadipose tissueasan endocrineorganwhich

is capable of.secreting,€unongothers,inflammato'rycytokines

It is.thereforepossible that a lack of sleep acting via[42].

the

regulatoryhormonesabovemay lead to un ln..eased fut

accumulationand increasedsecretionof pro_inflammatory

cytokines. There is evidence to suggeit that inflammatorv

processes

.may-!e important in obesity and may mediati

some of the effects observedwith intreaseOwiigtrt.

We

demonstrated

that an approximate2yo increasein solubleEselecrlntevetls associated

with a I unit higher BMI and a

0.01 unit greaterWaist-hip_rario (WHR)

J+51.eaiponectln,

which is a protectivecytokine however,'isnot reduced

in

qlt:nll with OSA comparedwith matchedcontrolswithout

OSA [44]. In a separatestudy, individuals with OSA

who

underwentCPAP treatmenthad associatedchangesin in_

flammatorymarkers(IL-6 and ICAM-l)

t451.ih; tevelsof

the inflammatorymarkerswere also associatedwith

resistin

levels. Likewise, CpAp treatmentdecreasedthe levels

of

ICAM-I and IL-8 [46]. prospective,longirudinal

srudies

nowever,are required to examine the causal link

-- between

sleepand obesityand inflammato.ymeaiato.s.

Glucoseand Insulin Regulation,Diabetes,Sleep

and In_

flammation.

Diabetescanleadto the development

of sleepabnormali_

ties. Findings from the SleepHeart Health Stuiy

indicated

thatdiabetesis associated

wiih periodicUr.utfrin!,a respira_

tory abnormalityassociatedwith changesin the ientral

con_

is thousht

fliutotuu.t, maybring

1a7..)...rr

T].:t"y^:ltllllon

about

sleepabnormalities

as a resultof its deleterious

effecti

on centralcontrol of breathing.However, it is also

important

to note.that sleep loss is associatedwith a decrease

in glucosetolerance,a highereveningcortisollevel and

increied

sympatheticactivity Fig. ( ). ireatment for OSA

has also

Deenassocrated

with beneficialchangesin insulinsensitivity

[45]. Furtherstudiesarerequiredto iivestigaG whetirersleep

losscanpredict changesin glucosernrtuUoirrn fr-ui.e

u.rru.

Laboratory

studies

of

healthy

young

adults,

demonstrated

.

that recurrent partial sleep re#iction-wa, ^r*iut.d

,ith

alterationsin glucosemetabolismincludingdecreaseO

glu_

cose tolerance and insulin sensitivity

[4d]. Furtherm6re,

sleeprestrictionled to changesin appeiite'control,in that

the

#legpf*s,#*rant6t$*fi

Seftsvi*ur s|**p rffifrtst*sn

e,g"n$**

e"g",ff

*rfsr$*wsfk*rtgh#ilrs

Sleepdeficit

t

t

I

i

lncreaseds)rnpath€fic

output

lncreasedeor{isol

*

l*sulin re,si* lrw

t

I

*

l$,*ightg*in

Fig, (a). Sleeploss,glucose& insulin regulation

Inflammation, Sleep, Obesity and Cardiovdscular Disease

levels of the anorexigenichormone leptin were decreased,

whereasthe levels of the orexigenicfactor ghrelin were increased(seepreviousFigure (effect ofsleep on energyregulating hormones)).These changeswere associatedwith an

increasein hungerand appetite.Over a long period this may

lead to weight gain, insulin resistanceand Type 2 Diabetes

[48]. A recentlongitudinalanalysisfrom the MONICA study

hasdemonstrated

that in both women and men the difficulty

in maintainingsleepas opposedto the difficulty in initiating

sleepwas associatedwith a higher risk of type 2 Diabetes

during the subsequent

mean follow-up period of 7.5 years

ll0l.

Theseand similar findingshave led to the suggestionthat

sleep and sleep disordersmay have a prominentrole on

metabolicand endocrinefunctions[49, 50]. Thereis a large

body of evidenceto suggestthat oxidative stressand inflammationplay a large role in the developmentof diabetes

and the developmentand progressionofthe associatedcomplications[51]. The exactcausalpathwaysremainto be elucidated and likewise it remains to be seen if the diabetic

complicationsassociatedwith sleep disturbanceshave an

underlyinginflammatorycomponent.

Blood Pressure,Sleepand Inflammation

Blood pressurenormally displays a nocturnaldip of

aboutl0% [52]. Non-dippersare at an inueasedrisk of CVD

and African Americans tend to display more non-dipping

characteristics

comparedto Caucasiansand this is associated

with an increasein sleepdisorderedbreathing[53]. SDB has

been identified as a risk factor for adversecardiovascular

outcomesin the elderly and is also associatedwith an increasein poststrokemortality[54]. Likewiseevidencesuggeststhat OSA palientshave an increasedincidenceof hypertension

comparedwith individualswithoutOSA, andthat

OSA is a risk factor for the developmentof hypertension[7].

Acute deprivationof sleep in healthy subjectsleads to an

increasein blood pressureand SNS activationand evidence

is growing,which suggeststhat there is a causalrelationship

betweenOSA syndromeand hypertension.[8]. A recentlongitudinal study demonstratedthat short sleepduration(<5 h

per night) was associatedwith a significantly increasedrisk

(hazud ratio,2.10;95yoCI, 1.58to 2.79)in

of hypertension

subjectsbetweenthe agesof 32 and 59 years.Furthermore,

adjustmentfor confoundingfactors such as obesity and diabetesonly partially attenuatedthis relationship[11]. Studies

demonstratedan associationbetweenhypertensionand inflammationbut potential causalpathwaysremain to be examinedin more detail. It is however of interestto note that

patientswith OSA exhibit increasedresting heart rate, decreasedtime duration betr.veen

fivo consecutiveR wavesof

the electrocardiogram(R-R interval) variability, and increasedblood pressurevariability. As well as observed

changesin inflammatory mediatorssuch as CRP. OSA is

also associatedwith changesin fibrinogen and plasminogen

activatorinhibitor [7], which are important in the developmentof hypertensionand cardiovasculardisease.

Lipids, Sleepand Inflammation

OSA may leadto hypoxia and the subsequentgeneration

of reactiveoxygenspecies(ROS). Thesein tum can lead to

Currmt VascularPharmacologlt,20M, VoL S, No. 2

5

an increasein lipid peroxidation.Indeed,increasedinflammatory markers and markers of oxidative stresshave been

found in patientswith OSA [55]. Although a recentstudy

concludedthat systemic inflammation is a characteristicof

OSA patientsit failed to find any differencein lipid peroxidation or antioxidantdefence (as measuredby superoxide

dismutase(SOD) betweenparientswith OSA (n=25) and

controls(n=17)[55].

MetabolicSyndrome,Sleepand Inflammation

Metabolic syndromeis characterised

by the clusteringof

cardiovascular

and metabolicrisk factorsin a given individual.Theseincludethe presence

ofcentralobesity,an adverse

lipid profile (high triacyglycerols

and low high densitylipoprotein(HDL) -cholesterol),

raisedblood pressure

and insulin resistance

or glucoseintolerance.It has also beensuggestedthat theremay be an increasedpro-inflammatorystate

[56]. Furthermore,Vgontzaset al. [57] clearlydemonstrated

that inflammatorycytokinesareincreasedin individualswith

OSA andthey proposedthat thesecytokineswerethe mediators of excessivedaytime sleepiness

(EDS). They demonstrated the importanceof visceral fat in OSA syndrome.

They suggestedthat sleepapneaand sleepinessin obesepatients may be manifestations

of the metabolicsyndrome.

Indeed in the US, data from the Third National Health and

Nutrition ExaminationSurvey(1988-1994)has shownthat

in the US population the prevalenceof the metabolicsyndromeparallelsthe prevalenceof symptomaticsleepapnoea

in generalrandomsamples[57].

Inflammation and Sleep

Immunemoleculesaltersleeparchitecture

andsleepdeprivation alters neuroendocrine

and immuneresponse[58].

Furthermore,immune systemactivationand neuroendocrine

responses

alter sleep [58]. In addition,sleep quality may

affect susceptibilityto infection,as well as onesability to

frghtoff infection[59]. The concentration

of high-sensitivity

CRP (hsCRP)is predictiveof future cardiovascularmorbidity [60] and at the sametime short sleepdurationand sleep

complaints are associatedwith increased cardiovascular

morbidity [9,23]. CRP levels are elevatedfollowing both

acute total and short term partial sleep deprivation [23].

Comparedwith control subjectsthe levelsof TNF-c, IL-6,

hsCRP,adhesionmolecules,and monocytechemoattractant

protein-l are markedly and significantly elevatedin patients

with sleepapnoea[61]. Short term sleepdeprivationgives

rise to a numberof effectson the immunesystemincludinga

decrease

in cellularimmuneresponseon the following day

to viral challengeis

12,62].Likewise,the immuneresponse

alsoreduced[63]. It remainsto be elucidated

whethersimilar

effects on the immune system are observedin individuals

with long-termsleepdeprivation.

As well as infectious agents,it is known that other diseasescan lead to an increasein systemicinflammationsuch

as arthritis.Studiesin patientswith rheumatoidarthritishave

revealedpattemsof sleepdisturbancesthat arc not associated

with the concomitantpain [64]. The innateimmunesystem

pathway can be activatedby the outer lipopolysaccharide

(LPS) componentof bacterialcell membranes[65]. Such

stimulationof the innateimmunesystemoccursthroughtoll-

6 Carrent Vascularpharmacologt,2007, VoI S, No.

2

like receptorsand can lead to an increasein inflammatory

cytokinesFig. (5).

LPS increasesNREM and reduceREM sleep in rabbits

[66]. In.rats, a 30 day infusion of LpS led ti a loss of

nypocretlnneurons.This suggests

that LpS and the resulting

inflamm.ation

may play a rolJ in the lossof hypocretinneuronswhichoccurin sleepdisorderssuchasnarcolepsy

[62].

^^In humanstudies,Gundersenet al. [6g) investigatedthe

effect of prolonged physical activity with'concomitant

en_

ergy and_

sleepdeprivationon leukocytefunction. They demonstrated.that leukocytesrespondedwith an increasingre_

Ieaseof inflammatorycytokineswhen challengedwith

LpS

as the study-progressed.Furthermore,they fiund that

the

responseto the anti-inflammatoryagenthydrocortisonewas

reduced.Theseresults demonstratethat multifactoral stress

can activateimmune cells and prime their responseto a microbial challenge[63]. However, it is importantto note that

sleep deprivationcan alter catecholamaines

[69], which in

turn may havean effect on white blood cells. The'exactpart

played and the importanceof the sleep deprivation

in rhis

multifactorialstressneedsto be further inu.rtigut.d.

The intermittenthypoxia/reoxygenation

processthat oc_

curs in OSA syndromeis associatedwith a ielective activa_

Miller and Cappuccio

tion of

.inflamm-at9ryprocessesas demonstratedby the increase in circulating tumour necrosis factor_alph; (TNF_

.

{pha) .andNFkappaB levels whereasadaptivepathwaysas

d_etermined

by the measurementof the aOaptiie regulator

HIF-l are not increased[70]. Fr:rthermore,CirAp theiapy

is

ableto normalisethe incieasedTNF_alphat.uet,

JZOI.ilsa

syndrome is associatedwith an increasedmonocyte

NFIuppug activity. Moreover this is also associatedwith an

increasedexpressionof iNOS protein

[71]. Furtherinformation on the links beh.veenthe innate immune system

and

sleepcanbe foundin a recentreview

[3].

Cortisol,-Sleep,the SympatheticNervous System(SNS),

Hylothalam ic pitu itary Adrenocortical (HiA)_axis

anO

Inflammation

Dysfunctionof the HpA axis at any level (corticotrophin

releasinghormone (CRH) receptor,giucocorti.oid r...itor,

or mineralocorticoidreceptor)ian dGrupt sleep

[72]. Sieep,

and.in particular_deep

sleep,has an inniUitoryinfluenceon

rne HrA axts, whereasactivation of the HpA axis leads

to

arousal [72]. Furthermore,excessivedaytime sleepiness,

as presentin sleepapnoea,narcolepsy,and idiopathic

luch

nypersomnla

are associated

with an increasein the secretion

*lrea* h*rmsnsn

Frc**smr?usarii*

Ertsldns*;**r#.ffia rxrn*t*rycaspNrlne,#:

ffi$ergy'regu*nllefxAFpgfftuEfifitr#*

Fig' (5). Possibleinteractionbetweenthe innateimmunesystemand sleepregulation

Inflammation, Sleep, Obesig and Cardiovascular Disease

of inflammatorymarkers[73]. It hasalsobeensuggested

that

HPA axis hyperactivitymay be a consequence

of OSA and

may indeedcontributeto secondarypathologiessuchas hypertensionand insulin resistance.[72]. On awakening,there

is a rise in cortisol levels.The time of awakeningand stress

are thoughtto influencethe magnitudeof the cortisol awakening response(CAR) 1741.A recentstudy which examined

men and women London Underground shift-workerssuggestedthat early-waking,stressearly in the day, and associated cortisol levels often coincide with sleep disturbance.

[74]. In a recentpilot study, which examinedthe sleepand

the stress-induced

cortisol responsein children and adolescents,there were signifrcantassociationsbetweenthe selfreportedsleep quality but not quantity and the cortisol response[75].

Depression,

Sleepand Inflammation

When comparedwith controls depressedpatientshave a

significantnocturnalincreasein circulatingIL-6 and sICAM

[76]. Furthermoreboth sleep latency and REM density are

associatedwith these inflammatory markers [76]. It is of

interestto note that in patientswith depression,total sleep

deprivationleadsto an increasein renin secretionand a concomitanttrend for a decreasein HPA axis activity in the recovery night [77]. lt has been suggestedthat thesechanges

could be a "fingerprint" of a rapidly antidepressive

treatment

1771.

SocialEconomicStatus (SES),Sleepand Inflammation

Low SESis frequentlyassociatedwith sleepdeprivation

and ethnic differencesin SES and sleeppatternsexist [78].

African American children have an increasein sleepdisordered breathing compared with white Caucasianswhich

could contributeto an increasein inflammatory processes

and associatedCVD risk [79]. However, further studiesare

requiredto examinethis hypothesis.

Alcohol,Sleepand Inflammation

There is someinconsistencyin the literaturebut in general it is acceptedthat moderate-to-large

quantitiesofalcohol

arecapableofaggravatingsevereOSA [80]. It hasalsobeen

suggestedthat there are inter-relationshipsbetweenalcoholism, sleeplossand ethnicity,which may also operatein a bidirectionalmanner[81]. It has beenpostularedthat disturbed

sleep patternseffect hormonal, autonomic nervous system

and immunefunction and might contributeto the increased

mortalityrateobservedin AfricanAmericanalcoholics[81].

Paediatrics,Sleepand Inflammation

Children with sleep disorderedbreathing have higher

CRP levelsthan childrenwho do not [82]. Furthermore,947o

of the children studied who had elevatedCRP levels also

reportedexcessivedaytimesleepinessor learningdifficulties

as comparedto 620/oof children who had CRP levels in the

normalrange[82].

Genes,Sleepand Inflammation

In the brain the sleep-wakecycle is regulatedby the central circadianoscillator in the hypothalamicsuprachiasmatic

nuclei (SCN) [83]. This oscillator is composedof many

Catmt

VasculdrPharmacolog420M, VoL S, No. 2

7

genesand proteins which interact together and have both

positiveand negativefeedbackloops [83]. Among others,

the CLOCK and BMALI elementspromotethe expression

of the Period(pefl, 2 and 3) and Crytochrome(Cryl | & 2)

genes.It is known that geneticvariationin someof these

genes,includingPeriod2, is importantin the development

of

somesleepdisorders[84].

Ifit is possibleto identift genesandgeneproductswhich

contributeto sleepdisordersit would be interestingto study

their associationsin children,as well as adults,as the former

are less likely to be influenced by age-associatedcomorbidities, which are present in the adult populations.

However,sleepdisordersdo exist in some childrenwhich

needto be excludedor diagnosed

in suchstudies.

A recent literaturereview led to the suggestionthat inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and Interleukin 1(L-1) perform neural functions in normal brainsAs such

they shouldbe regardedas both neuromodulators

as well as

inflammatory mediators [85]. The genes coding for these

cytokinesand their accessoryproteinsare expressedby glial

cells and neuronesin the normal brain [85]. Receptorsfor

thesecytokinesarepresenton neuralcells[85]. Patientswith

OSA syndromehave elevatedTNF-alphalevels [86]. The 308,4.TNF-alphagenepolymorphismis responsible

for increasedTNF-alphaproduction.Individualswith OSA syndrome and their siblings are more likely to carry this polymorphism than population controls; once more indicating

that an increasein inflammatorymediatorsmay be important

in thepathogenesis

of OSA syndrome[87].

Genetic and environmentalfactors may act togetherto

influencethe set-pointat which a given individual'sneroendocrine stressresponsesand cytokine production pattems

respondto different pathogensor antigens[S8]. It is therefore possiblethat geneticdeterminantsof sleepactingon the

oxidativeand immune pathwaysmay also be of importance

in determining an individual's subsequentcardiovascular

risk.

Sleepand PharmacologicalTreatments

OSA is characterizedby a collapse of the airway that

occursduringsleep[89]. As a resultthereis a lack ofoxygen

to the brain and the individual wakesup so that breathingis

resumed[89]. This canbe repeatedseveraltimesin onenight

and results in fragmentedsleep.One of the most common

treatrnentsfor this condition is CPAP [89]. This maintains

the airway during sleep.However, in some individualsthe

daytimesleepinessassociatedwith OSA and othersleepdisordersis not always eliminatedby this treatment.Although

the exact mechanismsthat govern the sleep-wakecycle and

the processare unknown.It is of interestto note that a relatively new drug, Modafinil is effective against excessive

daytimesleepiness[90]. It would appearthat this drug exerts

someof its action in the hypothalamus,which is an areaof

the brain that regulatessleep-wakefunctioning[90].

5-hydroxytryptophan

(5-HT) increasesserotoninlevels

and is usedto treat depression[91]. Therehas been some

suggestionthat it may improve sleeppatternsand aid weight

loss. A recent study, which investigatedthe effect of sleep

deprivation on 5-HT tumover, indicated that REM sleep

8

Current Vascular Pharmacologt, 2007, VoL S, No. 2

modulatedthe 5-HT tumover in the brain in a region_specific

manner[92].

Given the suggestionthat poor sleep may have cardiovascularconsequences

as a result of its effect on the inflam_

m?tor7ard oxidativepathway,it is possiblethat the pharmacologicalmanagement

of sleepdisordersmay need to in_

cludeanti-inflammatory

andantioxidantagentjaswell.

Miller and Cappuccio

It2l

tl 3 l

ll4l

Ilsl

The Importanceof Sleep

_ 91..p is a fundamentalrequirementfor living individuals.

In this review we discussedhow changesin sleep, acting

through inflammatorymechanisms,may be associatedwith

an increasedrisk of CVD. Changesin working pattemsand

increaseddemandson individual'stime ,"quire that more

individualsare awakefor longerperiodsoltime. Unfortu_

nately, increasesin shift work, on-call rotas and prolonged

working hours result not only in a potentially increasedcardiovascularrisk but also an increasedrisk of fatigue and ac_

cidentse.g. road traffic accidents,commutertra]n disasters

and pilot error as well as medical enors [93,94J.Driving

while drowsy has a similar effect to driving-undeithe influl

ence of alcohol. It is believed that substantialnumbersof

medicalerrorsresult from fatigue due to adversesleeppat_

terns in nursesand doctors[4]. Theseproblemstravea ]iigtr

cost both in terms of human life and economic factois.

Hence,it can be seenthat sleephas a major impacton our

healthandwell-being and needsto be researched

ihoroughly.

Some of theseproblems associatedwith the lack of Jleen

cou.ldbe_addressed

by improving our understandingof the

biologicalbasisof sleep;the biochemicalmechaniims;inv.olve.d,by-increasingawaxeness

both among health professionalsand amongthe lay public, and by making changesto

work patternsand accessto sleep recovery (naps/timi offl

aswell as improveddiagnosisandtreatmentresimes.

REFERENCES

tll

t21

t3l

t4l

t51

t61

l7l

t8l

t9l

UOl

tl ll

Siegel JM. Clues to the functions of mammalian sleep. Nature

2005;437:1264-71.

Irwin M. Effects of sleep and sleep loss on immuni8 and cytoki_

nes.BrainBehavImmun 2002:5:503-lZ.

Majde JA, Krueger JM. Links betweenthe innate immune svsrem

and sleep.J Allergy Clin Immunol2005; 116: I 188-98

Horrocks N, PounderR; RCp Working Group. Working the night

shift: preparation,survival and recovery--aguide forjunior doctors.

Clin Med 2006:6: 6l-7.

Ngtignll SleepFoundation.Sleep In America poll ..05: Summary

of Findings. Washington,DC: National Sleep Foundation: 200j.

http://www.sleepfoundation.

org/_content/hottopics/Slee

p_Segment

s.pdf

CaplesSM, Gami AS, SomersVK. Obstructive sleep apnea.Ann

IntemMed 2005; 142.187-97.

KasasbehE, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G, Inflammatory asDectsof

sleep apnoeaand their cardiovascularconsequences,

South Uea .l

2 0 0 6 ; 9 9 : 5 8 - 6 7q;u i z6 8 - 9 ,8 1 .

Narkiewicz K, Wolf J, Lopez-JimenezF, SomersVK. Obstructive

sleep.apnoea

and hypertension.

Cun CardiolRep2005;7:435_40.

Resnick HE, Howard BV. Diabetes and cardiovasculardisease.

Annu Rev Med 2002: 53:245-67.

Meisinger C, Heier M, Loewel H; MONIC{KORA Augsburg

Cohort Study. Sleep disturbanceas a predictor of type 2 diabetes

mellitus in men and women from the general population. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 23 5-41.

GangwischJE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-AlbalaB, Buijs RM, Kreier

F, Pickering TG, et al. Short Sleep Duration as a Risk Factor for

Hypertension.Analyses of the First National Health and Nutrition

ExaminationSurvey.Hypertension2006; 47: g33-9.

[16]

I17l

ttsl

llel

[20]

121l

122)

Kokturk O, Ciftci TU, Mollarecep E, Ciftci B. ElevatedC_reactrve

protein levels and increasedcardiovascularrisk in patientswith

ob_

structivesleepapnoeasyndrome.Int Heart J 2005;46:901-9

Prinz PN. Age impairmentsin sleep,metabolic and immune functions.Exp Gerontol2004; 39: 1739-43.

Strike PC, SteptoeA. New insights into the mechanismsof temporal variation in the incidence of acute coronary syndromes.Clin

Cardio2003;26: 495-9.

Peker Y, Hedner J, Norum J, Kraiczi H, CarlsonJ. Increasedincidenceof cardiovasculardiseasein middle_agedmen with obstruc_

lyg-d*_p apnea:a 7-year follow-up. Am J-RespirCrit Care Med

2002; 166: 159-65.

Redline S" Strohl K, Recognitionand consequences

of obstructlve

Ilfopnea syndrome.OtolaryngolClin North Am 1999;

1t3eg^1n19a

32:303-31.

Bliwise DL, King AC, Hanis RB. Habitual sleep durations and

health in a 50-65 ye:r old populatron.J Clin Epidimiol 1994; 47:

35-4r.

Vgontzas AN, Kales A. Sleep and its disorders.Annu Rev Med

1 9 9 9 t5 0 :3 8 7 - 4 0 0 .

Lugaresi E, Cirignotta F, Zucconi M, Mondini S, Lenzi pL, Coc_

cagnaC..Goodand poor sleepers: an epidemiological

surveyofthe

Jan Manno populatton.In : Sleep_Wake

Disorders: NaturalHis_

tory, Epidemiology and long-termEvolution. C. Guilleminaultand

E. Lugaresi(eds).New york, Ravenpressl9g3: 1_12.

K,alesA, SoldatosCR, Kales JD. Taking a sleephistory. Am Fam

Physicianl980;22: I 01-108.

Hak AE, Pols HA, StehouwerCD, Meijer J, Kiliaan AJ, Hofman

A, et al. Markers of inflammation and cellular adhesionmolecules

in relation to insulin resistancein nondiabeticelderly: the Rotterdam study.J Clin EndocrinolMetab200t; 86: 4398-4b5

Roubenoff R, P1riry H, payette HA, Abad LW, D'Agostino R,

JacquesPF, et al. Cytokines, insulin-like growth factoi I, sarcopenia, and mortality in very old community_dwellingmen

and

women: the FraminghamHeart Study. Am J Med 2003: ll5:429J)

[231

I24l

t2sl

t26l

I27l

[28]

I2el

t30l

[31]

t32l

t33l

134)

Meier-Ewert HK, tudker pM, Rifai N, Regan MM, price NJ,

Dinges DF, et al. Effect of sleep loss on C-reictive protein, an in_

flammatory marker of cardiovascularrisk. J Am Coll'Cardioi 2OO4:

43 678-83.

Stsininger TL, Hyder K, Apte-DeshpandeA, Ding J,

I:r.": 4,

RishipathakD, et al, Differcntial increasein the ixpression of heat

shock ptotein family membersduring sleepdeprivationand ourrng

sleep.Neuroscience2003 116: lg7-200.

Roy AK, Oh T, Rivera O, Mubiru J, Song CS, ChattedeeB. Im_

pactsoftranscriptional regulationon aging and senescenie.Ageing

ResRev 2002t 1:367-80.

Everson CA, Crowley WR. Reductions in circulating anabolic

hormones induced by sustainedsleep deprivation in its. em J

PhysiolEndocrinolMetab2004;286:El06b_70.

RestaO, Bonfitto P, SabatoR, De pergola G, BarbaroMp. preva_

lence ofobstructive sleepapnoeain a sampleofobese women: effect of menopause.

DiabetesNutr Metab20b4| 17:296_303.

Miller MA, SagnellaGA, Kerry SM, Srrazzullop, Cook DG, Cappuccio FP. Ethnic differencesin circulatingsolubleadhesionmole_

cules: the Wandsworth Heart and Stroke Study. Clin Sci (Lond)

2003; 104:559-60.

Knutson KL. Sex differencesin the associationbetweensleeDand

bodymassindexin adolescents.

J pediatr2005: I 47: g30_4.

BalarajanR. Ethnicity and variarionsin the nation'shealth.Health

Trends1995-96;27:114-9.

Scharf SM, Seiden L, DeMore J, Carter-pokrasO. Racial differ_

ences in clinical presentationof patients with sleeD_disordered

breathing.SleepBreath2004;8: | 73-83.

Buxbaum SG, Elston RC, Tishler pV, Redline S. Geneticsof the

apnea hypopnea index in Caucasiansand African Americans: I.

Segregationanalysis.GenetEpidemiol 2002:22: 243-53.

Poulain_M,D-oucetM, Major GC, DrapeauV, SeriesF, Boulet Lp,

et,al..T,heeffect of obesity on chronic respiratorydiseases:patho_

physiology and therapeuticstmtegies.CMAJ 2006; 174: l29i-g

Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong y, SternJS, plsunyer FX, er

al American Heart Association;Obesity Committeeof the Council

on Nutrition, PhysicalActivity, and Metabolism.Obesi8 and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of

weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association

Scientific Statementon Obesity and Heart Diseasefrom the Obe_

InJlammation, Sleep, Obesity and Cadiovascular Diseose

t35l

[36]

137)

[38]

l39l

sity Committeeof the Council on Nutrition, PhysicalActivity, and

Metabolism.

Circulation2006; 113:898-918.

SpiegelK, Tasali E, PenevP, Van CauterE. Briefcommunication:

Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associatedwith decreasedleptin levels, elevatedghrelin levels, and increasedhunger

and appetiteAnn Intem Med 2004; l4l:846-50.

Chaput JP, Brunet M, Tremblay A. Relationship between short

sleepinghours and childhood overweighVobesity:resultsfrom the

'Quebecen Forme'Project.Int

J Obes(Lond) 2006; [Epub aheadof

printl.

PatelSR, Malhofra A, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Hu FB. Short Sleep

Is a Risk Factor for Weight Gain, [Publication Page: A733 (Absrracr;ISS SanDiego)1.

Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleepduration is associatedwith reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increasedbody massindex. PLoS Medicine 2004; l: e62.

Dhamrait SS, StephensJW, Cooper JA, Acharya J, Mani AR,

Moore K, et al. Cardiovascular risk in healthy men and markers of

oxidative stressin diabeticmen are associatedwith common variation in the gene for uncoupling protein 2. Eur Heart J 2004;25:

Current Vascalar Pharmacologr, 2007, VoL 5, No. 2

t58l

t59l

[60]

16l]

t62l

t63l

t64l

468-7s.

[40]

l4ll

I42l

t43l

t44l

l45l

[46]

t47l

t48l

[49]

[50].

t5ll

t521

t53l

t54l

l55l

[56]

l57l

DAdamo M, Perego L, Cardellini M, Marini MA, Frontoni S,

Andreozzi F, et al. The -866NA genotype in the promoter of the

human uncoupling protein 2 gene is associatedwith insulin resistance and increasedrisk of type 2 diabetes.Diabetes 2004; 53:

I 905-t0.

Cirelli C, Tononi G. Uncoupling proteins and sleep deprivation.

Arch Ital Biol 2004; 142:541-9.

Trayhum P, Bing C, Wood IS. Adipose tissue and adipokinesenergy regulation from the human perspective. J Nutr 2006;

136(Suppl):

I 935S-l939S.

Miller MA, CappuccioFP. Cellular adhesionmoleculesand their

relationshipwith measuresof obesity and metabolicqyndromein a

multiethnicpopulation.Int J Obes(Lond) 2006; Mar 7 [Epub ahead

ofprintl.

Wolk & Svatikova A, Nelson CA, Gami AS, Govender K, Winnicki M, et al. Plasma levels of adiponectin,a novel adipocytederivedhormone,in sleepapnea.ObesRes2005; l3: 186-90.

Harsch IA, Koebnick C, Wallaschofski H, SchahinSP, Hahn EG,

Ficker JH, el a/. Resistin levels in patientswith obstructivesleep

apnoeasyndrome-the link to subclinical inflammation?Med Sci

Monit 2004: l0: CR510-5.

Ohga E, Tomita T, Wada H, Yamamoto H, NagaseT, Ouchi Y.

Effects of obstructive sleep apnea on circulating ICAM-I, IL-8,

and MCP-I . J Appl Physiol 2003;94: 179-84.

ResnicklIE, Redline S, ShaharE, Gitpin A, Newman A, Walter R,

et al. Sleep Heart Health Study. Diabetesand sleep disturbances:

findings from the Sleep Heart Health Study. DiabetesCare 2003;

26'.702-9.

SpiegelK, Knutson K, Leproult R, Tasali E, Van CauterE. Sleep

loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistanceand Type 2 diabetes.J

Appt Physiol2005;99: 2008-l9.

Boethel CD. Sleep and the endocrinesystem:new associationsto

old diseases.

Cun Opin Pulm Med 2002;8: 502-5.

ScheenAJ, Van CauterE. The roles oftime ofday and sleepquality in modulating glucose regulation: clinical implications. Horm

Res 1998;49: l9l-201.

Ceriello A. Oxidative stressand diabetes-associated

complications.

EndocrPract.2006; 12 (Suppl): 60-2,

Mallion JM, Baguet JP, Siche JP, Tremel F, De GaudemarisR.

Clinical value of ambulatory blood pressuremonitoring. J Hypert e n s1 9 9 9 ;l 7 : 5 8 5 - 9 5 .

PickeringTG, Kario K. Noctumal non-dipping:what doesit augur?

Cun OpinNephrolHypertens2001; 10:611-6.

BassettiCL, Milanova M, Gugger M. Sleep-DisorderedBreathing

and Acute Ischemic Stroke. Diagnosis, Risk Factors, Treatment,

Evolution, and Long-Term Clinical Outcome. Stroke 2006; 37:

967-72.

Alzoghaibi MA, Bahammam AS. Lipid peroxides, superoxide

dismutaseand circulating IL-8 and GCP-2 in patientswith severe

obstructivesleepapnoea:a pilot study. SleepBreath 2005; 9: I l9Vega GL. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome.Minerva Endocrinol2004;29: 47-54.

VgontzasAN, Bixler EO, ChrousosGP. Sleepapneais a manifestationof the metabolicsyndrome.SleepMed Rev 2005;9:211-24.

t65l

t66]

167l

168l

t69l

t70l

tTll

172)

l73l

174)

I75l

176l

t77l

t78l

t79l

t80]

9

Payne LC, Obal F Jr, Krueger JM. Hypothalamic releasinghormones mediatingtlte effects of interleukin-l on sleep.J Cell Bioc h e m1 9 9 3 ; 5 3 : 3 0 9 - 1 3 .

Edell-GustafssonUM. Sleep quality and responsesto insufficient

sleepin women on different work shifts.J Clin Nurs 2002; I l: 2807; discussion

288.

Clearfield MB. C-reactive protein: a new risk assessment

tool for

cardiovascular

disease.

J Am Osteopath

Assoc2005;105:409-16.

Teramoto S, Yamamoto H, Ouchi Y. IncreasedC-reactiveprotein

and increasedplasma interleukin-6 may synergisticallyaffect the

progressionof coronary atherosclerosisin obstructivesleep apnea

syndrome.Circulation 2003; 107: E40.

Bom J, Lange T, HansenK, Molle M, Fehm. Effects of sleepand

circadian rhythm on human circulating immune cells. J Immunol

1997;158:4454-64.

Lange T, PerrasB, Fehm HL, Bom J. Sleepenhancesthe human

antibody responseto hepatitis A vaccination. psychosom Med

2 0 0 3 ; 6 5 :8 3 1 - 5 .

Majde JA, Kruegar JM. Neuroimmunologyof sleep.In: D'haenen

H editor. Textbook of biological psychiatry.London: John Wiley

&Sons Ltd; 2002; p 1247-57.

RosenfeldY, Shai Y. Lipopolysaccharide(Endotoxinlhosr defense

antibacterialpeptidesinteractions:Role in bacterialresistanceand

preventionofsepsis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006; [Epub aheadof

printl.

Kruegar JM. Somnogenicactivity of immune responsemodifiers.

TrendsPharmacolSci 1990:11:122-6.

GerashchenkoD, ShiromaniPJ. Effects ofinflammation produced

by chronic lipopolysaccharideadministrationon the survival of

hypocretinneuronsand sleep.Brain Res2004; 1019 162-9.

GundersenY, OpstadPK, ReistadT, Thrane I, Vaagenesp. Seven

days' around the clock exhaustivephysicalexertioncombinedwith

energy depletion and sleep deprivation primes circulating leukocytes.Eur J Appl Physiol2006;97: 151-7.

Irwin M, Thompson J, Miller C, Giltin JC, Ziegler M. Effects of

sleepand sleepdeprivationon catecholamineand interleukin-2levels in humans:clinical implications.J Clin EndocrinolMetab 1999;

84:1979-85.

Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Selectiveactivation of inflammatory pathwaysby intermittenthypoxia in obstructivesleep

apnoeasyndrome.Circulation 20051'll2: 2660-7.

GreenbergH, Ye X, Wilson D, Htoo AK, HendersenT, Liu SF.

Chronic intermittent hypoxia activates nuclear factor-kappaBin

cardiovasculartissues ,n vryo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun

2006;343 591-6.

Buckley TM, SchatzbergAF. On the interactionsof the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal(HPA) axis and sleep:normal HpA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplarysleepdisorders.J Clin EndocrinolMetab2005t90: 3106-14.

Vgontzas AN, PapanicolaouDA, Bixler EO, Kales A, Tyson K,

ChrousosGP. Elevation of PlasmaCytokines in Disordersof ExcessiveDaytime Sleepiness:Role of Sleep Disturbanceand Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 19971'82:1313-6.

Williams E, Magid K, SteptoeA. The impact of rime of waking

and congurrentsubjectivestresson the cortisolresponseto awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology

2005;30: 139-48.

Capaldi Ii VF, HandwergerK, RichardsonE, Stroud LR. Associations betweensleepand cortisol responsesto str€ssin children and

adolescents:

a pilot study.BehavSleepMed 2005;3:177-92.

Motivala SJ, Sarfatti A, Olmos L, Irwin MR. Inflammatorymarkers and sleep disturbancein major depression.PsychosomMed

2005'.67:187-94.

Murck H, Uhr M, ZiegenbeinM, Kunzel H, Held K, Antonijevic

IA, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

system, HPA-axis and

sleep-EEGchangesin unmedicatedpatientswith depressionafter

total sleepdeprivation.Pharmacopsychiatry

2006;39: 23-9.

Van Cauter E, Spiegel K. Sleep as a mediator of the relationship

betweensocioeconomicstatusand health: a hypothesis.Ann N Y

Acad Sci 1999; 896 254-61.

Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, TostesonTD, Strohl KP, Spry K.

Racial differences in sleep{isordered breathing in AfricanAmericansand Caucasians.Am J RespirCrit CareMed 1997; 155:

186-192.

Heath M. Management of obstructive sleep apnoea.Br J Nurs

1993:2'.802-4.

l0

t8ll

t82l

[83]

t84l

t85l

t86l

_,

t87l

[88]

Current Vascular Pharmucologt, 2007, VoL S, No. 2

Irwin M, Rinetti G, Redwine L, Motivala S, Dang J, Ehters C.

Noctumal proinflammatory cytokine-associated

sleep disturbances

in abstinent African American alcoholics. Brain Behav Immun

2 0 0 4 :l 8 : 3 4 9 - 6 0 .

TaumanR, Ivanenko A, O'Brien LM, Gozal D. plasma C-reactive

protein levels among children with sleep_disordered

breathing.pe_

diatrics2004; 113:e564-9.

Leloup JC, GoldbeterA. Modeling the mammaliancircadranclock:

sensitivity analysis and multiplicity of oscillatory mechanisms.J

Theor Biol 2004t 230:541-62.

Tafti M, Maret S, Dauvilliers y. Genesfor normal sleepand sleep

disorders.Ann Med 2005; 37: 580-9.

Vitkovic L, Bockaert J, JacqueC. ,'Inflammatory"cytokines:neu_

romodulatorsin normal brain? J Neurochem2000;74:457-71.

Krueger JM, Majde JA. Humoral links betweenileep and the im_

mune system:researchissues.Ann N y Acad Sci. 2003;992,.9_20.

fuha RL, Brander P, Vennelle M, McArdle N, Ken SM, Anderson

NH, et al. Tumour necrosisfactor-alpha(_30g)genepolymorphism

in-otstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoeasyndr6me.'Eur Reipir J

2005;26:673-8.

Kunz-EbrechtSR, Mohamed-Ali V, Feldman pJ, Kirschbaum C,

St€ptoeA. Cortisol responsesto mild psychologicalsress are ln_

Rseived: July 26,2m6

Rwiscdr July 3 1,2006

AccepcdtAugust04,20(b

Miller and Cappuccio

.

[89]

t90l

[91]

t921

[93]

194)

versely associatedwith proinflammatory cytokines. Brain Behav

Immun2003; 17: 373-83.

Victor LD. ObstructiveSleepApnea.Am Fam physicran1999:60:

2279-86.

Lin JS, Hou Y, Jouvet M. potential brain neuronaltargetsfor amphetamine-,methylphenidate-,and modafinil_inducedwakefulness,

evidenced by c-fos immunocytochemistryin the cat. hoc Natl

Acad Sci USA 1996;93: 14128-t4133.

Birdsall TC. s-Hydroxytryptophan:a clinically-effectiveserotonin

precursor.AlternMed Rev 1998;3:271-g0.

SenthilvelanM, Ravindran R, SamsonJ, Devi RS. Serotonintumover in different duration of sleep recovery in discreteregions of

young rat brain after 24h REM sleepdeprivation.Brain DJv 2006;

28:526-8.

Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, KaushalR, Burdick E,

Katz JT, et al. Effect of reducing intems, work hours on serious

medicalerrorsin intensivecare units. N Engl J Med 2004;351:

I 838-48.

Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan

CP, et al. Harvard Work Hours, Health and SafetyGroup.Effeciof

reducing intems, weekly work hours on sleep and attentionalfail_

ures.N Engl J Med 2004: 351: lt29-37.