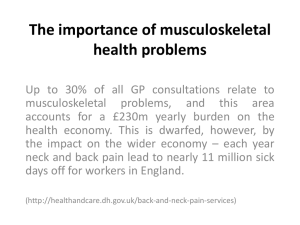

Clinical and cost-effectiveness of manual therapy and non-musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic

advertisement