An evaluation of a short-term, cognitive-behavioural intervention for primary age

advertisement

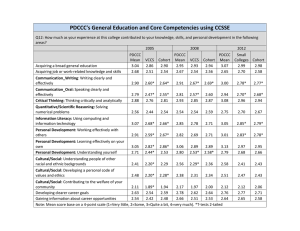

An evaluation of a short-term, cognitive-behavioural intervention for primary age children with anger-related difficulties Rachel Cole Individual or group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has a strong evidence base for targeting anger and self-control issues in young people with emotional and behavioural difficulties (Bennet & Gibbons, 2000; Sukhodolsky, Kassinove & Gorman, 2004). However, few empirical studies focus on the effectiveness of cognitivebehavioural interventions for adolescents and children with angerrelated difficulties separately – despite the conclusions of some meta-analyses that effect sizes vary for the two populations (ibid ). Of the empirical studies which do distinguish between child and adolescent populations, there are far fewer studies focusing exclusively on children under the age of 12 with anger-related difficulties than on adolescents (Koegl, Farrington, Augimeri & Day, 2008), leading some to conclude that there is more research needed in this area (Jouglin, 2006). My research question Can short-term, CBT-based anger management groups produce improvements in behaviour, emotional literacy, anger and peer acceptance, in primary-age children? The Study Results Participants 70 children between the ages of 7 and 11, from 12 primary schools. Design • Utilised a quasi-experimental, mixed group design. • Groups within schools were matched on participants’ pre-intervention conduct scores on a teacher completed Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997), and then randomly allocated to cohorts. • Schools receiving the intervention in Phase 1 of the study were labelled Cohort IN (intervention, no-intervention); Phase 2 schools were labelled Cohort NI (no intervention, intervention). Intervention Key Stage 2 Anger Management programme, ‘Learning How to Deal with Our Angry Feelings’, an unpublished six-week, group work course for 7-11 year olds (Faupel, Herrick & Sharp, 1998). Measures (a)Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). (b)Emotional Literacy Student and Teacher checklists (Faupel, 2003). (c)Anger Management Pre/Post Assessment tool (Southampton Psychology Service, 2003). (d)Like To Play (LITOP) Questionnaire (the Social Inclusion Survey, Frederickson & Graham, 1999). While both cohorts yielded statistically significant improvements in their understanding of anger directly post-intervention, only the second cohort (NI) made statistically significant improvements in general behaviour and emotional literacy. SDQ total scores according to time and cohort 18.00 Mean SDQ scores (total) CBT-based interventions for young people with anger-related difficulties Kent County Council / University College London 17.00 Cohort 16.00 _______ 15.00 14.00 NI IN 13.00 12.00 1 2 3 time Neither cohort made improvements in anger levels or peer perception scores. Discussion • Cohort IN did not show statistically significant improvements on most measures directly post-intervention or at follow-up. Only the measure of participants’ understanding of anger as an emotional state showed significant improvement directly post-intervention, an effect which was maintained at follow-up. • Cohort NI showed both a statistical improvement in understanding of anger as an emotional state, and in measures of general behaviour and emotional literacy. This suggests that while both cohorts recalled learned aspects of the intervention (calming down strategies and bodily responses to anger), the intervention only changed participants’ and teachers’ perceptions of behaviour and emotional literacy for Cohort NI. Several potential reasons might account for these unexpected findings. Two are considered particularly pertinent: 1.Differences in pro-social skills: While the cohorts were matched on most measures pre-intervention, there were statistical differences on prosocial scores on the SDQ, and the peer acceptance scores on the SIS, in favour of Cohort NI. It is possible that this Cohort, with more social skills and greater peer acceptance, were more receptive to the intervention - particularly given the socially oriented, group nature of the programme being evaluated. 2.Differences in school-level factors: In comparison to national averages, schools in Cohort NI have average results, and lower levels of social deprivation, whilst schools in Cohort IN have below average results, high levels of children with statements and high levels of social deprivation. While the makeup of the individual children in the two cohorts was similar, it is possible that clear systemic differences may have affected the efficacy of the intervention.