The Faerie Queene

advertisement

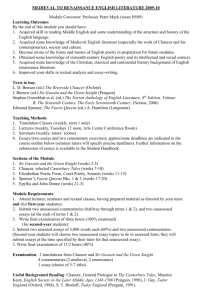

How to read The Faerie Queene Spenser’s life c. 1552 Born in London. 1569-73 Studies at Cambridge. 1578 Secretary to the Bishop of Rochester. 1579 Marries Machabyas Childe. 1580 Secretary to the Lord Deputy of Ireland. 1594 Death of Machabyas. 1595 Marries Elizabeth Boyle. 1598 Tyrone rebellion. Spenser leaves Ireland. 1599 Dies in London. Spenser’s principal works 1579 1590 1595 1596 1598 The Shepheardes Calender The Faerie Queene, books 1-3 Amoretti and Epithalamion The Faerie Queene, books 4-6 A View of the Present State of Ireland. Spenser’s principal works 1579 1590 1595 1596 1598 Shepheardes Calendar The Faerie Queene, books 1-3 Amoretti and Epithamamion The Faerie Queene, books 4-6 A View of the Present State of Ireland. Spenser’s principal works 1579 1590 1595 1596 1598 The Shepheardes Calendar The Faerie Queene, books 1-3 Amoretti and Epithamamion The Faerie Queene, books 4-6 A View of the Present State of Ireland ‘... because the beginning of the whole worke seemeth abrupt and as depending upon other antecedents ...’ (A Letter of the Author’s) The purpose of the poem: ‘The general end ... of all the book is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline; which for that I conceived should be most plausible and pleasing being coloured with an historical fiction – the which the most part of men delight to read, rather for variety of matter than for profit of the ensample – I chose the history of king Arthur, as most fit for the excellency of his person, being made famous by many men’s former works, and also furthest from the danger of envy and suspicion of present time.’ (A Letter of the Author’s) Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci, lectorem delectando pariterque monendo. [Horace, Ars poetica, 343-44] He who mixed the useful with the pleasurable won great acclaim, delighting and instructing the reader in equal measure. The purpose of the poem: ‘The general end ... of all the book is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline; which for that I conceived should be most plausible and pleasing being coloured with an historical fiction – the which the most part of men delight to read, rather for variety of matter than for profit of the ensample – I chose the history of king Arthur, as most fit for the excellency of his person, being made famous by many men’s former works, and also furthest from the danger of envy and suspicion of present time.’ (A Letter of the Author’s) The models of the poem: ‘I have followed all the antique poets historical: first Homer, who in the persons of Agamemnon and Ulysses hath ensampled a good governor and a virtuous man, the one in his Ilias, the other in his Odysseis; then Virgil, whose like intention was to do in the person of Aeneas; after him, Ariosto comprised them both in his Orlando; and lately Tasso ...’ (A Letter of the Author’s) Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1590 Vergil, Aeneid, 1590 I am he who once tuned my song on a slender reed, then, leaving the woodland, I compelled the neighbouring fields to obey the eager farmer, a work welcome to husbandmen; but now of Mars’ bristling... Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1590 Vergil, Aeneid, 1590 Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, 1516-1532 English tr. by John Harington, 1591 Torquato Tasso, La Gerusalemme liberata, 1581 English tr. by Thomas Carew, 1594 (part), and Edward Fairfax, 1600 (complete) Ariosto, 1556 Spenser, 1590 Harington, 1591 The ‘Spenserian stanza’ •Nine lines in total. •Eight lines in iambic pentameter (10 syllables, 5 iambic feet). •Final line in iambic hexameter (12 syllables, 6 iambic feet, an ‘Alexandrine’). •Rhyme pattern ABAB BCBC C. First stanza A gentle Knight was pricking on the plaine, Ycladd in mightie armes and silver shielde, Wherein old dints of deepe wounds did remaine, The cruel markes of many a bloudy fielde; Yet armes till that time did he never wield: His angry steede did chide his foming bitt, As much disdayning to the curbe to yield: Full jolly knight he seemd, and faire did sitt, As one for knightly giusts and fierce encounters fitt. Rhyme pattern ABAB BCBC C A B A B B C B C C Spenserian medievalisms From Chaucer: ‘eyen’, ‘doen’, ‘ycladd’, ‘raught’, ‘seely’, ‘stowre’, ‘swinge’, ‘owch’, ‘withouten’. From Layamon, Wyclif, and Langland: ‘swelt’, ‘younglings’, ‘noye’, ‘kest’, ‘hurtle’. Others: ‘brent’, ‘cruddled’, ‘forswat’, ‘fearen’, ‘pight’, ‘carle’, ‘carke’. Protestantism vs Catholicism Simile: ‘This man is like a dog’ Simile: ‘This man is like a dog’ Metaphor: ‘This man is a dog’ Simile: ‘This man is like a dog’ Metaphor: ‘This man is a dog’ Allegory = ‘sustained metaphor’? George Puttenham, The Arte of English Poesie, 1589: Allegoria is when we do speak in sense translative and wrested from the own signification, nevertheless applied to another [and] having much conveniencie with it; ... as, for example, if we should call the commonwealth a ship; the prince a pilot; the counsellors mariners; the storms wars; the calm and haven peace. George Puttenham, The Arte of English Poesie, 1589: Allegoria is when we do speak in sense translative and wrested from the own signification, nevertheless applied to another [and] having much conveniencie with it; ... as, for example, if we should call the commonwealth ‘a ship’; the prince ‘a pilot’; the counsellors ‘mariners’; the storms ‘wars’; the calm and haven ‘peace’. My galley, charged with forgetfulness, Thorough sharp seas in winter nights doth pass 'Tween rock and rock; and eke mine en'my, alas, That is my lord, steereth with cruelness; And every owre a thought in readiness, As though that death were light in such a case. An endless wind doth tear the sail apace Of forced sighs and trusty fearfulness. A rain of tears, a cloud of dark disdain, Hath done the wearied cords great hinderance; Wreathed with error and eke with ignorance. The stars be hid that led me to this pain. Drowned is reason that should me consort, And I remain despairing of the port. Thomas Wyatt Botticelli, The Calumny of Apelles ‘To some I know this method will seem displeasaunt, which had rather have good discipline delivered plainly in way of precepts, or sermoned at large ... than thus cloudily enwrapped in allegorical devices. But such ... should be satisfied with the use of these days, seeing all things accounted by their shows, and nothing esteemed of that is not delightful and pleasing to common sense. … So much more profitable and gracious is doctrine by ensample than by rule.’ (A Letter of the Author’s) Stanza 1 A gentle Knight was pricking on the plaine, Ycladd in mightie armes and silver shielde, Wherein old dints of deepe wounds did remaine, The cruel markes of many a bloudy fielde; Yet armes till that time did he never wield: His angry steede did chide his foming bitt, As much disdayning to the curbe to yield: Full jolly knight he seemd, and faire did sitt, As one for knightly giusts and fierce encounters fitt. Stanza 1 A gentle Knight was pricking on the plaine, Ycladd in mightie armes and silver shielde, Wherein old dints of deepe wounds did remaine, The cruel markes of many a bloudy fielde; Yet armes till that time did he never wield: His angry steede did chide his foming bitt, As much disdayning to the curbe to yield: Full jolly knight he seemd, and faire did sitt, As one for knightly giusts and fierce encounters fitt. Stanza 2 But on his brest a bloudie crosse he bore, The deare remembrance of his dying Lord, For whose sweete sake that glorious badge he wore, And dead as living ever him ador’d: Upon his shield the like was also scor'd, For soveraine hope, which in his helpe he had: Right faithfull true he was in deede and word, But of his cheere did seeme too solemne sad; Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad. Stanza 2 But on his brest a bloudie crosse he bore, The deare remembrance of his dying Lord, For whose sweete sake that glorious badge he wore, And dead as living ever him ador’d: Upon his shield the like was also scor'd, For soveraine hope, which in his helpe he had: Right faithfull true he was in deede and word, But of his cheere did seeme too solemne sad; Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad. Stanza 4 A lovely Ladie rode him faire beside, Upon a lowly asse more white then snow, Yet she much whiter, but the same did hide Under a vele, that wimpled was full low, And over all a blacke stole she did throw, As one that inly mournd: so was she sad, And heavie sat upon her palfrey slow; Seemed in heart some hidden care she had, And by her in a line a milke white lambe she lad. Stanza 4 A lovely Ladie rode him faire beside, Upon a lowly asse more white then snow, Yet she much whiter, but the same did hide Under a vele, that wimpled was full low, And over all a blacke stole she did throw, As one that inly mournd: so was she sad, And heavie sat upon her palfrey slow; Seemed in heart some hidden care she had, And by her in a line a milke white lambe she lad.