Medieval to Renaissance Renaissance Commentary Spring 2016

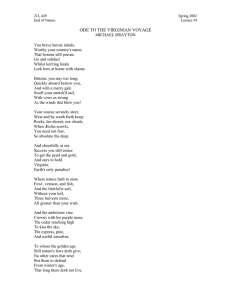

advertisement

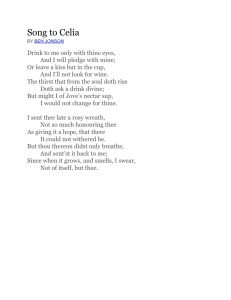

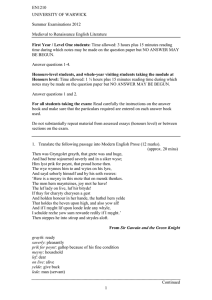

Medieval to Renaissance Renaissance Commentary Spring 2016 Please write an approx. 1000 word commentary on ONE of the following poems / pairs of poems / prose extracts. You may wish to discuss some of the following: content, choice of vocabulary, metaphor, poetic technique, poetic form, point of view, argument, assumed audience and sequence of ideas. Please submit one paper copy of your commentary to your seminar tutor in week 7 (exact time to be specified by tutor). Please also make an electronic submission by 5pm on Friday of week 7. 1. Compare the following two sonnets by Thomas Wyatt and Edmund Spenser as responses to Petrarch’s Rima 189 (translated in Norton Anth. p. 652). My galley My galley charged with forgetfulness Thorough sharp seas, in winter nights doth pass ‘Tween rock and rock; eke mine enemy, alas, That is my lord, steereth with cruelness; And every oar a thought in readiness, As though that death were light in such a case. An endless wind doth tear the sail apace Of forced sighs and trusty fearfulness. A rain of tears, a cloud of dark disdain, Hath done the wearied cords great hinderance; Wreathed with error and eke with ignorance. The stars be hid that led me to this pain. Drowned is reason that should me consort, And I remain despairing of the port. Thomas Wyatt Sonnet 34, from Amoretti Lyke as a ship that through the Ocean wyde, By conduct of some star doth make her way Whenas a storme hath dimd her trusty guyde, Out of her course doth wander far astray: So I whose star, that wont with her bright ray Me to direct, with cloudes is overcast, Doe wander now in darknesse and dismay, Through hidden perils round about me plast. Yet hope I well, that when this storme is past My Helice the lodestar of my lyfe Will shine again, and looke on me at last, With lovely light to cleare my cloudy grief. Till then I wander carefull comfortlesse, In secret sorow and sad pensivenesse. Edmund Spenser placed guiding star full of cares Helice: a name for the Big Dipper. 2. But the whole matter can be cleared up if you’ll ask Raphael about it – either directly, if he’s still in your neighbourhood, or else by letter. And I’m afraid you must do this anyway, because of another problem that has cropped up – whether through my fault, or yours, or Raphael’s, I’m not sure. For it didn’t occur to us to ask, nor to him to say, in what area of the New World Utopia is to be found. I wouldn’t have missed hearing about this for a sizable sum of money, for I’m quite ashamed not to know even the name of the ocean where this island lies about which I’ve written so much. Besides, there are various people here, and one in particular, a devout man and a professor of theology, who very much wants to go to Utopia. His motive is not by any means idle curiosity, but rather a desire to foster and further the growth of our religion, which has made such a happy start there. To this end, he has decided to arrange to be sent there by the pope, and even to be named bishop to the Utopians. He feels no particular scruples about intriguing for this post, for he considers it a holy project, rising not from motives of glory or gain, but simply from religious zeal. Therefore I beg you, my dear Peter, to get in touch with Hythloday – in person if you can, or by letters if he’s gone – and make sure that my work contains nothing false and omits nothing true. It would probably be just as well to show him the book itself. If I’ve made a mistake, there’s nobody better qualified to correct me; but even he cannot do it, unless he reads over by book. Besides, you will be able to discover in this way whether he’s pleased or annoyed that I have written the book. If he has decided to write out his own story for himself, he may be displeased with me; and I should be sorry, too, if, in publicizing Utopia, I had robbed him and his story of the flower of novelty. But to tell the truth, I’m still in two minds as to whether I should publish the book or not. For men’s tastes are so various, the tempers of some are so severe, their minds so ungrateful, their judgements so foolish, that there seems no point in publishing something, even if it’s intended for their advantage, that they will receive only with contempt and ingratitude. Better simply to follow one’s own natural inclinations, lead a merry, peaceful life, and ignore the vexing problems of publication. Most people know nothing of learning; many despise it. The clod rejects as too difficult whatever isn’t cloddish. The pedant dismisses as mere trifling anything that isn’t stuffed with obsolete words. Some men approve only of ancient authors; most men like their own writing best of all. Here’s a man so shallow he won’t allow a shadow of levity, and there’s one so insipid of taste that he can’t endure the salt of a little wit. Thomas More, from Letter from Thomas More to Peter Giles, Utopia 3. Too dearly had I bought my grene and youthfull yeres, If in mine age I could not finde when craft for love apperes; And seldom though I come in court among the rest, Yet can I judge in colours dim as depe as can the best. Where grief tormentes the man that suffreth secret smart, To breke it forth unto som frend it easeth well the hart. So standes it now with me for my beloved frend: This case is thine for whom I fele such torment of my minde, And for thy sake I burne so in my secret brest That till thou know my whole disseyse my hart can have no rest. I see how thine abuse hath wrested so thy wittes That all it yeldes to thy desire, and folowes thee by fittes. Where thou hast loved so long with hart and all thy power, I see thee fed with fayned wordes, thy fredom to devour. I know, though she say nay and would it well withstand, When in her grace thou held thee most, she bare thee but in hand. I see her pleasant chere in chiefest of thy suite: When thou art gone I see him come, that gatheres up the fruite. And eke in thy respect I see the base degre Of him to whom she gave the hart that promised was to thee. I see, what would you more? Stode never man so sure On womans word, but wisdome would mistrust it to endure. deceived, led astray Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey 4. Second Song Have I caught my heav'nly jewel, Teaching sleep most fair to be? Now will I teach her that she, When she wakes, is too, too cruel. Since sweet sleep her eyes hath charm'd, The two only darts of Love: Now will I with that boy prove Some play, while he is disarm'd. Her tongue waking still refuseth, Giving frankly niggard "No": Now will I attempt to know What "No" her tongue sleeping useth. See, the hand which waking guardeth, Sleeping, grants a free resort: Now will I invade the fort; Cowards Love with loss rewardeth. But, oh, fool, think of the danger Of her just and high disdain: Now will I alas refrain, Love fears nothing else but anger. Yet those lips so sweetly swelling Do invite a stealing kiss: Now will I but venture this, Who will read must first learn spelling. Oh sweet kiss. But ah, she is waking. Lowering beauty chastens me: Now will I away hence flee. Fool! More fool for no more taking. Philip Sidney, Astrophil and Stella 5. O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem By that sweet ornament which truth doth give. The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem For that sweet odour which doth in it live. The canker-blooms have full as deep a dye As the perfumèd tincture of the roses, Hang on such thorns, and play as wantonly When summer’s breath their maskèd buds discloses; But, for their virtue only is their show, They live unwooed, and unrespected fade, Die to themselves. Sweet roses do not so Of their sweet deaths are sweetest odours made: And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth: When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth. William Shakespeare, Sonnet 54 vade: lose vitality