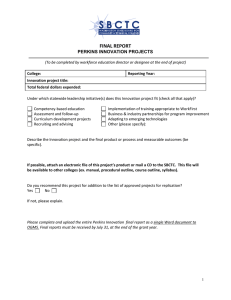

Competency-Based Education Programs in Texas An Innovative Approach to

advertisement