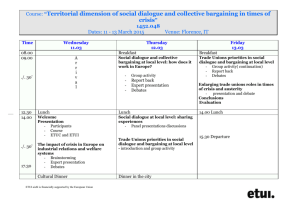

New structures, forms and processes of governance in European industrial relations

advertisement