Research Paper

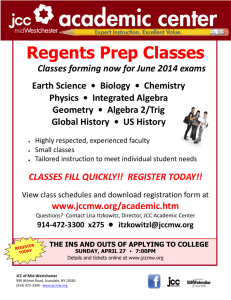

advertisement