Drivers of Long-Term Insecurity and Instability in Pakistan Urbanization

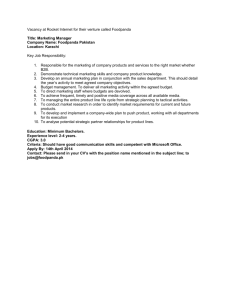

advertisement