Future EU External Action Budget Focus on Development March 2012

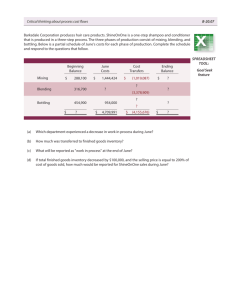

advertisement