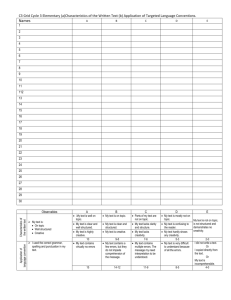

1. Course Outline 2. Bibliographies 3. Reflective Piece Analysis

advertisement