A Student-Delivered Patient Safety Seminar for Pre-clinical Undergraduate Medical Students

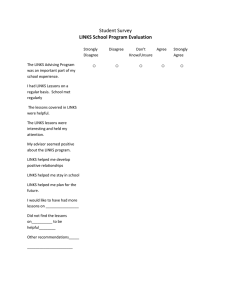

advertisement