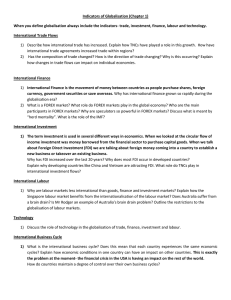

3 / The Impact of Globalisation and Global Economic Crises

advertisement