Review of International Studies (2009), 35, 729–749 Copyright

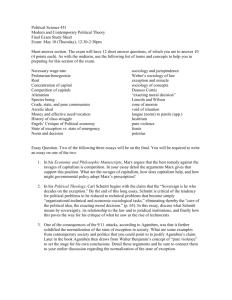

advertisement

Review of International Studies (2009), 35, 729–749 Copyright British International Studies Association

doi:10.1017/S0260210509990155

The generalised bio-political border?

Re-conceptualising the limits of sovereign

power

NICK VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS*

Abstract. This article is a response to calls from a number of theorists in International

Relations and related disciplines for the need to develop alternative ways of thinking ‘the

border’ in contemporary political life. These calls stem from an apparent tension between

the increasing complexity of the nature and location of bordering practices on the one hand

and yet the relative simplicity with which borders often continue to be treated on the other.

One of the intellectual challenges, however, is that many of the resources in political thought

to which we might turn for new border vocabularies already rely on unproblematised

conceptions of what and where borders are. It is argued that some promise can be found

in the work of Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, whose diagnosis of the operation of

sovereign power in terms of the production of bare life offers significant, yet largely

untapped, implications for analysing borders and the politics of space across a global

bio-political terrain.

Introduction

Borders are vacillating [. . .] they are no longer at the border, an institutionalised site that

could be materialised on the ground and inscribed on the map, where one sovereignty ends

and another begins.1

Étienne Balibar

If Étienne Balibar’s pithy observation is taken seriously then the debate about the

status of borders between states in contemporary political life appears to be

somewhat missing the point. According to this familiar inter-disciplinary debate,

which is often associated with arguments about the character and extent of

globalisation, state borders are characterised either as a thing of the past or as an

enduring feature of world politics post-1648.

* An earlier version of this article was presented at the 48th Annual Convention of the International

Studies Association, Chicago, IL, 28 February – 3 March 2007. Special thanks are due to Mathias

Albert, Jenny Edkins, Yosef Lapid, Hidemi Suganami, R.B.J. Walker, the Editorial team of the RIS

and two anonymous reviewers. An extended version of the argument presented here can be found

in N. Vaughan-Williams, Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power (Edinburgh and New York:

Edinburgh/Columbia University Press, 2009).

1

E. Balibar, ‘The Borders of Europe’, trans. J. Swenson, in P. Cheah and B. Robbins (eds),

Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond the Nation (London and Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1998), pp. 217–8.

729

730

Nick Vaughan-Williams

The former discourse has it that the transformation of global production,

involving the growth of multi-national companies, a 24 hour market and

post-Fordist industries, has rendered the notion of a national economy obsolete.2

On this view, economic change is said to have ushered in new patterns of

governance, in which the role of the modern, sovereign, territorially bordered state

has diminished.3 Consequently, it is sometimes argued that the erosion of state

borders over recent decades threatens the very idea of the so-called Westphalian

territorially defined international states-system.4

By contrast, the latter discourse maintains that national economies have been

left intact if not actually strengthened by globalisation.5 From this perspective, the

modern state, paradigmatically defined by Max Weber as ‘a human community

that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of force within a given

territory’,6 remains the primary political entity in global politics.7 Moreover,

especially since the attacks on the twin towers of the World Trade Centre and the

Pentagon on 11 September 2001, some writers now argue that state borders are

more important than ever before.8 Yet, according to this tired and totalising

debate, the focus is on the presence/absence of state borders, rather than the

possibility, as hinted at by Balibar, that the concept of the border is playing out

in different and often unexpected ways at a multiplicity of sites in contemporary

political life.

In the context of the theoretical lexicon of International Relations (IR),

R. B. J. Walker has diagnosed a dominant spatial-temporal logic of inside/outside.9

Spatially, discourses of international relations presuppose a series of demarcations

between inside and outside, here and there and us and them, in order to affirm the

effect of the ‘presence’ of sovereign political community. Temporally, these

demarcations work to secure a primary distinction between a realm of progress

‘inside’ and a realm of immutable violence, warfare and barbarism ‘outside’. On a

preliminary reading, therefore, the concept of the border of the state conditions the

possibility of thinking in the above terms and this border is taken to be located at

the geographical outer-edge of sovereign territory.

As such, the concept of the border of the state can be said to frame the limits

of sovereign power as something supposedly contained within fixed territorially

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

C. Brown, ‘Globalisation’, in C. Brown with K. Ainley (eds), Understanding International Relations,

3 (Hampshire and New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005), p. 167.

S. Strange, ‘The Westfailure System’, Review of International Studies, 25:3 (1999), pp. 345–54.

D. Held and A. McGrew (eds), The Global Transformations Reader: An Introduction to the

Globalisation Debate (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), p. 39; J. A. Scholte, Globalisation: A Critical

Introduction (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2000), pp. 135–6.

P. Hirst and G. Thompson, ‘Globalisation in Question’ (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000); P. Hirst and

G. Thompson, ‘The Future of Globalisation’, Cooperation and Conflict, 37 (2002), pp. 255–66.

M. Weber, ‘Politics as a Vocation’, in H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (eds), From Max Weber: Essays

in Sociology (London: Kegan Paul, 1948), p. 78.

B. Carlson, J. Warner and K. Wang, ‘Foreword’, The SAIS Review of International Affairs, Special

Issue on ‘Borders’, 26:1 (Winter-Spring, 2006), pp. 1–2.

H. Starr, ‘International Borders: What They Are, What They Mean, and Why We Should Care’,

The SAIS Review of International Affairs, Special Issue on ‘Borders’, 26:1 (Winter-Spring, 2006),

pp. 3–10; E. Zureik and M. Salter, ‘Introduction’, in E. Zureik and M. Salter (eds), Global

Surveillance and Policing: Borders, Security, Identity (Cullompton, Devon and Portland, Oregon:

Willan Publishing, 2005), p. 1; D. Newman, ‘Borders and Bordering: Towards an Inter-Disciplinary

Dialogue’, p. 181.

R. B. J. Walker, ‘Inside/outside: International Relations as Political Theory’ (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1993).

The generalised bio-political border?

731

demarcated parameters. This is illustrated by Weber’s influential formulation in

which the realm of sovereign power (‘successful claims to the monopoly of the

legitimate use of force’) is defined by territorial borders (‘within a given territory’).

In turn, the inside/outside model conditioned by the concept of the border of the

state provides a powerful foundation for the theory and practice of international

relations: it is codified in international law by the norm of ‘territorial integrity’ (see

Article 2 Paragraph 4 of the UN Charter); it acts as an epistemological and

ontological anchor on the basis of which seemingly diverse conceptualisations of

global politics proceed; and, as Anthony Jarvis and Albert Paolini have pointed

out, it allows for a compartmentalisation of global politics into two supposedly

distinct spheres permitting a division of labour between Politics on the one hand

and IR on the other.10

However, despite the imperiousness of the inside/outside model conditioned by

the concept of the border of the state, a growing number of critical scholars concur

with Balibar’s observation about the paradoxical and complex nature of borders in

contemporary political life. Walker, for example, not only diagnoses the logic of

inside/outside but also seems to call this logic into question throughout many of

his texts.11 Hence, he argues that, ‘We have shifted rather quickly from the

monstrous edifice of the Berlin Wall, perhaps the paradigm of a securitized

territoriality, to a war on terrorism, and to forms of securitization, enacted

anywhere.’12 In the same vein, Achille Mbembe has argued, ‘in [the] heteronymous

organisation of territorial rights and claims, it makes little sense to insist on

distinctions between “internal” and “external” political realms, separated by clearly

demarcated boundaries’.13 Similarly, Zaki Laïdi refers to ‘a global social system in

which there is no longer a frontier between internal and external’.14 Moreover,

albeit in different ways and contexts, Louise Amoore,15 Didier Bigo,16 David

Campbell,17 Yosef Lapid,18 Noel Parker,19 Chris Rumford,20 Gearóid Ó Tuathail

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

A. Jarvis and A. Paolini, ‘Locating the State’, in J. Camilleri, A. Jarvis, and A. Paolini (eds), The

State in Transition: Reimagining Political Space (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1995), pp. 1–4.

Walker frequently implies the inadequacy of the inside/outside model conditioned by the concept of

the border of the state, see: R. B. J. Walker, ‘Inside/outside’, p. 20, p. 159, p. 161; R. B. J. Walker,

‘Sovereignty, Identity, Community: Reflections on the Horizons of Contemporary Political Practice’

in R. B. J. Walker and S. H. Mendlovitz (eds), Contending Sovereignties: Redefining Political

Community (Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1990), p. 180; R. B. J. Walker

‘Foreword’ in J. Edkins, N. Persram and V. Pin-Fat (eds), Sovereignty and Subjectivity (Boulder and

London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999), p. xii; R. B. J. Walker, ‘On the Immanence/Imminence

of Empire’, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 31:1 (2002), p. 343; and Walker, After the

Globe/Before the World (Unpublished manuscript) p. 1.

R. B. J. Walker, ‘International/inequality’, International Studies Review, 4:2 (2002), p. 17.

A. Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, trans. L. Meintjes, Public Culture, 15:1, pp. 11–40. See also A. Mbembe,

‘At the Edge of the World: Boundaries, Territoriality and Sovereignty in Africa’, Public Culture, 12

(2000), pp. 259–84.

Z. Laïdi, ‘A World Without Meaning: the Crisis of Meaning in International Politics’ (London:

Routledge, 1998), p. 97.

L. Amoore, ‘Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror’, Political Geography,

25 (2006), pp. 336–51.

D. Bigo, ‘The Möbius Ribbon of Internal and External Security(ies)’, in M. Albert, D. Jacobson and

Y. Lapid (eds), Identities, Borders, Orders: Rethinking International Relations Theory (Minnesota and

London: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), pp. 91–116.

D. Campbell, ‘Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity’

(Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1998).

Y. Lapid, ‘Introduction: Identities, Borders, Orders: Nudging International Relations Theory in a

New Direction’, in M. Albert et al (eds), Identities, Borders, Orders, p. 2.

732

Nick Vaughan-Williams

and Simon Dalby,21 Michael J. Shapiro,22 William Walters,23 to name only a few,

have all made claims about the need for alternative border imaginaries in the study

of global politics.

Yet, despite these insistences, there has been relatively little work on the

development and application of new and innovative ways of border thinking in IR.

On the one hand, as Walker has argued, such reticence is perhaps unsurprising

given the stakes involved: ‘better explanations – of contemporary political life – are

no doubt called for, but they are unlikely to emerge without a more sustained

reconsideration of fundamental theoretical and philosophical assumptions than can

be found in most of the literature on international relations theory’.24 On the other

hand, there is a danger of a growing disjuncture between the increasing complexity

and differentiation of borders in global politics and the apparent simplicity and

lack of imagination with which borders continue to be identified and analysed.

In this article, I argue that there are potentially useful resources for developing

alternative border imaginaries to be found in the recent work of Italian philosopher

Giorgio Agamben. The following discussion begins with a detailed exegesis of some

of Agamben’s key arguments as articulated in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and

Bare Life (1998), Means Without End: Notes on Politics (2000), State of Exception

(2005) and several key essays and interviews. By now, the use of Agamben in IR

has become popular in the study of diverse aspects of the ‘War on Terror’,25

especially in relation to debates about the rule of law and sovereign exceptionalism,26 although his work has not gone without criticism.27 Departures will be made

from extant interpretations of Agamben’s work, however, in respect of his central

concept of ‘bare life’, the importance of what he calls ‘a logic of the field’ and,

perhaps most importantly, the implications of his oeuvre for an understanding of

the spatial dimensions of sovereign power. Building upon what I consider to be a

distinctive reading of Agamben, I then develop the idea of the ‘generalised

bio-political border’ as a re-conceptualisation of the limits of sovereign power: not

as fixed territorial borders located at the outer-edge of the territorial state, but

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

N. Parker, ‘A Theoretical Introduction: Spaces, Centres, and Margins’, in N. Parker (ed.), The

Geopolitics of Europe’s Identity: Centres, Boundaries, and Margins (Basingstoke and New York:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), pp. 3–24.

C. Rumford, ‘Introduction: Theorising Borders’, European Journal of Social Theory, 9:2 (2006),

pp. 155–69.

G. Ó Tuathail and S. Dalby (eds), Rethinking Geopolitics (London: Routledge, 1996), p. 29.

M. J. Shapiro, ‘Violent Cartographies: Mapping Cultures of War’ (Minnesota: University of

Minnesota Press, 1997).

W. Walters, ‘Mapping Schengenland: Denaturalising the Border’, Environment and Planning (D):

Society and Space, 20:5, (2002), pp. 564–80 and W. Walters, ‘Border/Control’, European Journal of

Social Theory, 9:2 (2006), pp. 187–203.

R. B. J. Walker, ‘Inside/outside’, p. 159.

A. Closs Stephens and N. Vaughan-Williams (eds), Terrorism and the Politics of Response (London

and New York: Routledge, 2008); E. Dauphinee and C. Masters (eds), Living, Dying, Surviving: the

Logics of Biopower and the War on Terror (New York: Palgrave, 2007); J. Edkins, V. Pin-Fat, and

M. J Shapiro, (eds), Sovereign Lives: Power in Global Politics (New York: Routledge, 2004).

A. Neal, ‘Exceptionalism and the Politics of Counter-Terrorism: Liberty, Security, and the War on

Terrorism’ (London and New York: Routledge, 2009); M. Neocleous, ‘The Problem with Normality:

Taking Exception to “Permanent Emergency”’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 31 (2006),

pp. 191–293; S. Prozorov, ‘X/Xs: Towards a General Theory of the Exception’, Alternatives: Global,

Local, Political, 30 (2005), pp. 81–112.

J. Butler, ‘Precarious Life: the Powers of Mourning and Violence’ (London and New York: Verso,

2004); W. Connolly, ‘The Complexity of Sovereignty’, in J. Edkins et al, Sovereign Lives, pp. 23–41.

The generalised bio-political border?

733

infused through bodies and diffused across society and everyday life. As I will

suggest, thinking in terms of the generalised bio-political border has potentially

radical implications for the way we conceptualise what and where borders are in

global politics, which, in turn, raises some provocative questions for IR and

security theorists.

Giorgio Agamben: indistinction, sovereign power, and bare life

Over the past twenty years or so, Giorgio Agamben has attempted a critique of the

dominant treatment of the relation between politics and life in political philosophy.28 According to Agamben, the main influence in the Western context has been

Aristotle’s account of the connection between the state and the human in his

Politics. In the First Book, Aristotle presents the rise of the polis as the joining

together of families and villages. The state, originating in ‘the bare needs of life’,

continues to exist for ‘the sake of the good life’.29 Since for Aristotle ‘the state is a

creation of nature’, he argues that ‘man is by nature a political animal’ or ‘politikon

zōon’.30 Thus, he who is without a state is ‘[. . .] either above humanity, or below it:

he is the “tribeless, lawless, hearthless one” whom Homer denounces – the outcast

who is a lover of war’.31 To be fully human, therefore, one must be a member of the

polis for it is only here that the good life can be achieved.

In Agamben’s reading, the distinction between ‘natural life’ on the one hand

and the ‘good life’ in the polis on the other is at the heart of Aristotle’s conception

of the state. According to Agamben, this distinction reflects the way in which the

Greeks had no single word for ‘life’. Rather, he claims, two terms were used in its

place: zoē (the biological fact of life common to all living beings) and bios (political

or qualified life).32 As such, the private realm of zoē is taken to be simply excluded

from bios, understood as the politically qualified life of the public sphere. Agamben

notes that the key insights of Aristotle’s Politics – his definition of man as a

political animal, his opposition between the simple fact of living and politically

qualified life, and his distinction between private and public spheres – have all had

a lasting impact on the political tradition of the West. Nevertheless, Agamben

argues that these insights concerning the relationship between politics and life have

largely been assumed rather than interrogated within political thought. For

Agamben, however, one notable exception is the work of Michel Foucault.33

28

29

30

31

32

33

At the time of writing the Homo Sacer series translated into English includes: G. Agamben, ‘Homo

Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life’ (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998); ‘Remnants of

Auschwitz: the Witness and the Archive’ (New York: Zone Books, 1999); and ‘State of Exception’,

(Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Ibid., p. 28.

Ibid., p. 28.

Ibid., p. 28.

See G. Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 1 and G. Agamben, ‘Form-of-Life’, in P. Virno and M. Hardt

(eds), Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1996), p. 151.

By now there is growing literature on the relationship between Agamben and Foucault, which,

especially in the Politics and IR literature, tends to privilege the importance of the latter over

the former. See, for example, A. Neal, ‘Cutting Off the King’s Head: Foucault’s Society Must

Be Defended and the Problem of Sovereignty’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 29 (2004),

734

Nick Vaughan-Williams

In The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: The Will to Power (1976), Foucault

refers to the process by which biological life (zoē) has become included within the

modalities of state power (bios). He captures this inclusion in terms of the

transition from politics to bio-politics with reference to the emergence in the 17th

century of attempts to govern populations as populations. Foucault argues that,

whereas for Aristotle life and politics are considered separate, bio-politics takes life

itself as its referent object: ‘modern man is an animal whose politics calls his

existence as a living being into question’.34 On this view, the entry of zoē into bios

has occasioned a fundamental shift in the nexus between politics and life, where the

simple fact of life is no longer excluded from political calculations and mechanisms

but absolutely central to modern politics.

At certain points in the book Homo Sacer it seems as though Agamben agrees

fully with Foucault’s historical schematisation. For example, in his introduction,

Agamben writes, ‘the entry of zoē into the sphere of the polis [. . .] constitutes the

decisive event of modernity and signals a radical transformation of the politicalphilosophical categories of classical thought’.35 But while Agamben is highly

indebted to Foucault he argues that ‘the Foucauldian thesis will [. . .] have to be

corrected, or at least completed’ because a historical shift to bio-politics has not

actually taken place.36 Agamben makes a different claim from Foucault’s about the

historical-philosophical structure of the West: ‘the production of a bio-political

body is the original activity of sovereign power’.37 In other words, whereas

Foucault reads the movement from politics to bio-politics as a historical

transformation involving the inclusion of zoē in the realm of the polis, for Agamben

the political realm is originally bio-political. On Agamben’s view, the West’s

conception of politics has always been bio-political, but the nature of

the relation between politics and life has become more exposed in the context of

the modern state and its sovereign practices.38

Agamben shows how the originally bio-political element of politics can be seen

to be at play in Aristotle’s definition of the polis in terms of the exclusion of zoē

from bios. For Agamben, this ‘exclusion’ of zoē is not entirely exclusive, because

zoē still remains in a fundamental relation with bios. Indeed, zoē is included in bios

through its very exclusion from it: as Jenny Edkins puts it, ‘natural life or zoē is

there as that which is excluded, the outlaw that haunts the sovereign order’.39 We

are not dealing with a straightforward exclusion, therefore, but what Agamben

calls an ‘inclusive exclusion’. To explain this paradoxical formulation he introduces

a spatial-ontological device used by Jean-Luc Nancy: the ban.40 If someone is

‘banned’ from a political community he or she continues to have a relation with

that group: there is still a connection precisely because they are outlawed. In this

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

pp. 373–98; A. Neal, ‘Foucault in Guantanano: Towards an Archaeology of the Exception’, Security

Dialogue, 39:1 (2006), pp. 31–46; M. Ojakangas, ‘Impossible Dialogue on Bio-Power: Agamben and

Foucault’, Foucault Studies, 2 (May 2005), pp. 5–28.

(Quoted in) Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 3.

Ibid., p. 4.

Ibid., p. 9.

Ibid., p. 6 (emphasis in original).

Ibid., p. 6.

J. Edkins, ‘Trauma and the Memory of Politics’(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003),

p. 180.

J-L Nancy, ‘Abandoned Being’, trans. B. Holmes, in J-L Nancy (ed.), The Birth to Presence

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), pp. 36–47.

The generalised bio-political border?

735

way, the figure of the banned person thus complicates the simplistic dichotomy

between inclusion and exclusion. As we shall see, the idea of an ‘inclusive

exclusion’ is important in Agamben’s theoretical edifice because it is pivotal in his

account of the Western paradigm of sovereign power.

Agamben’s treatment of sovereignty is influenced by Carl Schmitt’s definition

of the sovereign as ‘he who decides on the exception’.41 According to Schmitt, such

a decision declares that a state of emergency exists and suspends the rule of law

to allow for whatever measures are deemed to be necessary in response. In addition

to the Schmittian logic, however, Agamben also invokes Walter Benjamin’s critique

that ‘the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of exception” in

which we live is the rule’.42 I shall return to the Schmitt-Benjamin debate in greater

detail but for now suffice it to say that Agamben’s diagnosis of the relation

between politics, life, and sovereignty fuses Nancy’s concept of the ban, Schmitt’s

definition of sovereignty, and Benjamin’s idea of the permanent state of exception.

For Agamben, sovereign power relies on the ability to decide on whether

certain forms of life are worthy of living. Such a decision, which is a sovereign cut

or dividing practice, produces an expendable form of life that Agamben calls ‘bare

life’. The sovereign decision bans bare life from the legal and political institutions

to which citizens normally have access. This ban renders bare life amenable to the

sway of sovereign power and allows for exceptional practices such as indefinite

detention, torture, or even (but not inevitably) execution. Importantly, bare life is

neither what the Greeks referred to as zoē nor bios. Rather, it is a form of life that

is produced in a zone of indistinction between the two. Agamben, therefore, argues

that it is necessary to identify and analyse the way in which the classical distinction

between zoē and bios is blurred in contemporary political life: ‘Living in the state

of exception that has become the rule has [. . .] meant this: our private body has

now become indistinguishable from our body politic’.43

Elaborating on his ‘correction’ of the Foucauldian thesis, Agamben thus argues

that the decisive characteristic of modern politics is not so much the simple

inclusion of zoē in bios, but rather:

The decisive fact is that, together with the process by which the exception everywhere

becomes the rule, the realm of bare life – which is originally situated at the margins of the

political order – gradually begins to coincide with the political realm, and exclusion and

inclusion, outside and inside, bios and zoē, right and fact, enter into a zone of irreducible

indistinction.44

This ‘zone of irreducible indistinction’ is precisely that which sovereign power relies

upon producing in order to sustain its own operation. What Agamben ultimately

seeks to show is that the production of bare life is the originary (if concealed)

activity of sovereign power. Before dealing with his central claim about the

relationship between sovereignty and subjectivity, however, it is first necessary to

41

42

43

44

C. Schmitt, ‘Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty’, trans. G. Schwab,

3rd Edition, (Chicago and London: the University of Chicago Press, 2005).

W. Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, in H. Eiland and M. Jennings (eds), Walter Benjamin:

Selected Writings, Volume 4, 1938–1940 (Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of

Harvard University Press, 2003) [1940], pp. 389–400.

G. Agamben, ‘Means Without Ends: Notes on Politics’, trans. V. Binetti and C. Casarino

(Minnesota: University of Minneapolis Press, 2000), p. 139.

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 9 (emphasis added).

736

Nick Vaughan-Williams

unpack and illustrate aspects of Agamben’s central thesis. His understanding and

usage of key terms such as ‘zones of indistinction’ and ‘bare life’ are not always

clear or even consistent: there is a need to take them as areas for debate rather

than as simple givens.

The politics of indistinction: towards a ‘logic of the field’

Agamben contends that thinking in terms of borders, separations, and distinctions

is actually quite unhelpful when trying to understand the relationship between

politics and life. This contention is significant when trying to come to terms with

the privileged status he affords to otherwise seemingly idiosyncratic concepts such

as ‘inclusive exclusion’, ‘the ban’, and ‘zones of indistinction’. In an interview

published in the German Law Review, Agamben argues for an approach to the

study of politics that allows for the identification and analysis of what he calls

indistinction:

[W]e need a logic of the field, as in physics, where it is impossible to draw a line clearly and

separate two different substances. The polarity is present and acts at each point of the field.

Then you may suddenly have zones of indecidability or indifference. The state of exception

is one of those zones.45

Agamben’s reference to the need for a ‘logic of the field’ gestures towards the

importance of one of the key insights of developments in theoretical physics at the

beginning of the last century: that entities within the electromagnetic field are not

mutually exclusive phenomena but physically continuous within their milieu of

interaction.46 On this view, the flow of electrons and protons renders entity x

always already part of entity y: entities are shown to interpenetrate each other,

collapse into each other and are thus inseparable from each other from the outset.

Accordingly, ‘a logic of the field’ provides an alternative paradigm of thought

in which the concept of the border no longer makes much sense. Such a logic reads

binary oppositions such as inside/outside not as ‘dichotomies’ but as ‘di-polarities’,

not substantial, but tensional’.47 In order to illustrate this alternative topological

register, Agamben makes reference to the figure of the Möbius strip: a surface with

only one side so that what is ‘presupposed as external [. . .] now reappears [. . .] in

the inside’.48 Whereas the zone of indistinction remains obscured within the

horizon of an inside/outside topological relation it is brought into relief when

thinking in terms of a logic of the field. Such a shift is paramount for Agamben

since it provides a spatial theory that informs his analysis of sovereign power and

the nomos – or spatial-juridical orientation – of the West: ‘It is precisely this

topological zone of indistinction [. . .] that we must try to fix under our gaze’.49

45

46

47

48

49

G. Agamben, ‘Interview with Giorgio Agamben – Life, A Work of Art Without an Author: the State

of Exception, the Administration of Disorder, and Private Life’, German Law Review, 5:5 (2004)

p. 612.

See A. N. Whitehead, ‘Science and the Modern World: the Lowell Lectures 1925’ (London: Free

Association Books, 1985) and S. Kwinter, ‘Architectures of Time: Toward a Theory of the Event in

Modernist Culture’ (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

G. Agamben, ‘Interview with Giorgio Agamben’, p. 612.

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 37.

Agamben, Ibid, p. 37.

The generalised bio-political border?

737

As I have already noted, Agamben applies a ‘logic of the field’ to his analysis

of the relationship between politics and life by focusing on the classical distinction

between zoē and bios.50 He argues that in order to better understand the logic of

sovereign power it is necessary to isolate and analyse the way in which the classical

distinction between zoē and bios gets blurred in contemporary political life. It is

within the zone of indistinction between zoē and bios that sovereign power

produced bare life: a form of life that scrambles the Aristotelian co-ordinates with

which the relationship between politics and life is conventionally studied. Bare life

is a form of life that is amenable to the sway of sovereign power because it is

precisely caught in a sort of legal and political vacuum conducive to the permanent

instantiation of ‘exceptional’ practices. According to Agamben, the ‘locus par

excellence’ of contemporary blurring of zoē and bios and the production of bare

life is the detention camp at the US Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay.51

Bare life in Guantánamo Bay

Despite the centrality of the concept of bare life in Agamben’s work, it nevertheless

remains somewhat elusive and a site of debate.52 Indeed, there is sufficient

ambiguity (and inconsistency) in Agamben’s usage of the concept for a multiplicity

of possible interpretations to emerge. Many writers who draw on Agamben refer

to bare life as if it were synonymous with zoē.53 I want to suggest, however, that

a more faithful reading is one that sees bare life as a form of life produced

immanently by sovereign power in a zone of indistinction between zoē and bios:

The foundation (of the modern city from Hobbes to Rousseau) is not an event achieved

once and for all but is continually operative in the civil state in the form of the sovereign

decision. What is more the latter refers immediately to the life (and not the free will) of

citizens, which thus appears as the originary political element. [. . .] Yet this life is not simply

natural reproductive life, the zoē of the Greeks, nor bios, a qualified form of life. It is, rather,

the bare life of homo sacer [. . .], a zone of indistinction and continuous transition between

man and beast, nature and culture.54

On this alternative reading, bare life is not something antecedent to or outside

of sovereign power relations. It is not something we are born with and can be

stripped down to: ‘life conceived as a biological minimum [. . .] to which we are all

50

51

52

53

54

Ibid., p. 612.

G. Agamben, ‘Interview with Giorgio Agamben’, p. 612.

The term ‘bare life’ is Daniel Heller-Roazen’s translation of ‘nuda vita’, contained in the sub-title

of Agamben’s original Homo Sacer: Il Potere Sovrano e la Nuda Vita. However, not all scholars

agree with this translation. For example, Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino translate ‘nuda vita’

as ‘naked life’, see ‘Translators’ Notes’ in G. Agamben, ‘Means Without End’, p. 143.

See, for example, J. Edkins and V. Pin-Fat, ‘Through the Wire’. Edkins and Pin-Fat note that the

concept of bare life is contentious and open to different readings. However, they set-up and use the

terms ‘bare or naked life’ and ‘zoē’ interchangeably (pp. 6–7). For other examples of this tendency

see: J. Butler, ‘Precarious Life’, p. 67; J. Edkins, ‘Missing Persons: Manhattan, September 2001’ in

E. Dauphinee and C. Masters (eds), Living, Dying, Surviving; C. Lausten and B. Diken, ‘Zones of

Indistinction: Security, Terror, and Bare Life’, Space and Culture, 5:3 (2002), pp. 290–307; A. Norris,

‘Giorgio Agamben and the Politics of the Living Dead’ in A. Norris (ed.), Politics, Metaphysics, and

Death: Essays on Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer (Durham and London: Duke University Press,

2005); and M. Ojakangas ‘Impossible Dialogue on Bio-Power: Agamben and Foucault’, Foucault

Studies, 2 (May 2005), p. 7.

G. Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 109 (Emphasis added).

738

Nick Vaughan-Williams

reducible’.55 Bare life is not zoē: any attempt at qualifying life as ‘bare’ or ‘good’

is a move away from zoē.56 Rather, as Agamben states clearly, bare life is

something that is actively produced by sovereign power for sovereign power: ‘bare

life is a product of the machine and not something that pre-exists it’.57 What

Agamben shows is that sovereign power depends upon creating and exploiting

zones of indistinction in which subjects’ recourse to conventional legal and political

protection is curtailed: a technique of governance he argues is illustrated by the

status of detainees held indefinitely at Guantánamo Bay.

As is by now well known, the US government established the detention centre

at Guantánamo Bay in January 2002 to hold suspected terrorists captured in

Afghanistan. Since its establishment approximately 520 detainees from 40 different

countries have been held there, some of who are cab drivers, farmers and 13

year-old children.58 A UN report on the ‘Situation of detainees at Guantánamo

Bay’ highlights the conditions under which they are detained. Detainees are housed

in 8ft by 8ft cells with wire walls, metal roofs and permanent electric lighting.

Interrogation methods, approved by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld,

consist mainly of: the use of stress positions (like standing) for up to four hours;

isolation up to 30 days; sensory deprivation; removal of comfort items; forced

grooming; use of individual phobias (for example, fear of dogs) to induce stress.59

Other policies include: degrading treatment (such as the removal of clothing –

sometimes in the presence of women); cultural and religious harassment (such as

using female interrogators to perform ‘lap dances’ and kicking the Holy Koran);

and beating detainees who resist.60 Moreover, the uncertainty generated by the

indeterminate nature of confinement has, according to the UN, led to serious

mental health problems: as of 13 June 2006 there have been three suicides and

many more attempted suicides.

Detainees in Guantánamo are held in what Amnesty International calls a ‘legal

black hole’.61 Under the ‘Military Order on the Detention, Treatment and Trial of

Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism of 13 November 2001’ (hereafter the

‘Military Order’), the US government has denied most detainees the right to trial

and legal counsel.62 As such, the UN has concluded that the US is in breach of

the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which seeks to

guarantee the right to challenge the lawfulness of detention before a court (ICCPR,

Art. 9(4)) and the right to a fair trial by a competent, independent and impartial

court of law (ICCPR, Art.14). According to the US Defense Department, the

indefinite detention of suspected terrorists in Guantánamo is a ‘military and

security necessity’ in the context of the global ‘War on Terror’.63 As the UN report

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

J. Butler, ‘Precarious Life’, p. 67.

I must acknowledge my thanks to Alex Murray for this formulation.

Agamben, ‘State of Exception’, pp. 87–8.

Response of the United States of America, dated 21 October 2005, to the inquiry of the Special

Rapporteurs of the UN dated 8 August 2005 pertaining to detainees at Guantanamo Bay, p. 52.

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, ‘Situation of

Detainees in Guantanamo Bay’, 15 February 2006, E/CN.4/2006/120, p. 24.

Ibid., pp. 24–5.

{http://web.amnesty.org/pages/guantanamobay-index-eng}

In June 2004 the Supreme Court held that US courts have jurisdiction to consider challenges to the

legality of detention of foreign nationals in Guantanamo. However, no habeas corpus petition has

been decided on the merits by a US Federal Court. E/CN.4/2006/120, p. 15.

Ibid., p. 3 (Emphasis added).

The generalised bio-political border?

739

points out, however, detention ‘without charges or access to counsel for the

duration of hostilities’ amounts to a radical departure from established principles

on human rights law.64 Further still, as far as the UN is concerned, the global

struggle against international terrorism ‘does not, as such, constitute an armed

conflict for the purposes of the applicability of international humanitarian law’.65

Formally, the Bush administration classified detainees held in Guantánamo as

‘unlawful enemy combatants’, but this is not a term recognised by the UN or any

other international institution.66 Such a classification itself constitutes ‘arbitrary

deprivation of the right to personal liberty’ since it creates a deliberate legal and

political ambiguity surrounding detainees’ status.67 In contravention of Article 5 of

the Third Geneva Convention, and despite repeated calls from the International

Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), none of the detainees have been declared

prisoners of war or presented before a competent tribunal in order to establish who

or what they are.68 It is precisely this production of a deliberate uncertainty

surrounding the status of detainees that allows for the indefinite use of exceptional

measures against them. As ‘pure killing machines’, Guantánamo detainees are not

deemed to be ‘humans with cognitive function’ who are ‘entitled to trials, to due

process, to knowing and understanding a charge against them’.69 Rather, as Judith

Butler argues, ‘they are something less than human, and yet – somehow – they

assume a human form’.70 Indeed, the subject of sovereign power in Guantánamo

is precisely ‘the subject who is no subject, neither alive nor dead, neither fully

constituted as a subject nor fully deconstituted in death’.71

Guards who stand watch over the detainees in Guantánamo confront a peculiar

form of ‘human life’. Stripped of political and legal status, it bears no resemblance

to Aristotle’s conception of man as politikon zōon in the public sphere or bios. Yet,

importantly as far as the interpretation of Agamben advanced here is concerned,

neither does this life in any simple way conform to what the Greeks would have

called zoē. Rather, the life confronted by the guards is a life that scrambles these

Aristotelian co-ordinates: we no longer have any idea of the classical separation

between zoē and bios in this context.72 It is a bare life produced by the sovereign

practices of the camp that is caught in a zone of indistinction between zoē and bios:

a life that is mute and undifferentiated. For Agamben, such a life belongs to homo

sacer or sacred man: a figure in Roman law whose very existence is in a state of

exception defined by the sovereign. The figure of homo sacer is sacred in the sense

that it can be killed but not sacrificed and is both constituted by and constitutive

of sovereign power. Moreover, as the state of exception is arguably less anomalous

and more a permanent characteristic, according to Agamben we all run the risk of

becoming bare life: ‘we are all (virtually) homines sacri’.73

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

Ibid., p. 12.

E/CN.4/2006/120, p. 13.

Ibid., p. 12.

Ibid., p. 12.

The UN report on the situation of detainees in Guantanamo points out that the US government

relies upon the deliberate cultivation of ambiguity in order to flout the Geneva Conventions.

E/CN.4/2006/120, p. 23.

Butler, ‘Precarious Life’, p. 98.

Ibid., p. 74.

Ibid., p. 98.

G. Agamben, ‘Means Without End’, p. 138.

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 111.

740

Nick Vaughan-Williams

The problem of sovereignty and subjectivity in Agamben

Agamben’s seemingly hyperbolic claim that we are ‘all (virtually) homines sacri’

raises many interesting and important questions that are not dealt with explicitly

in his oeuvre to-date: What is meant by the idea that we are all ‘virtually’ bare life?

Does the concept of bare life allow for any form of differentiation between

subjects? What are the limitations of adopting Agamben’s logic of sovereign

power? How might it be elaborated upon?

Though highly indebted to Agamben, Butler argues that the universality

implied by the claim that we are all ‘virtually homines sacri’ exposes an area of

weakness in his understanding of political subjectivity. Butler’s chief criticism of

Agamben is that he does not tell us how ‘power functions differentially’ among

populations.74 Focusing on issues of race and ethnicity, Butler argues that the

generality of Agamben’s treatment of the political subject fails to appreciate the

ways in which ‘the systematic management and derealization of populations

function to support and extend the claims of a sovereignty accountable to no

law’.75 For Butler, certain populations are more likely to be produced as bare life

than others. Although security warnings issued to citizens do not currently involve

overt racial profiling, Butler suggests that the creation of an ‘objectless panic’ all

too often ‘translates [. . .] into suspicion of all dark-skinned peoples, especially

those who are Arab, or appear to look so to a population not always versed in

making visual distinctions’.76 As such, Butler’s criticism presses Agamben’s

thesis on its tendency to universalise and over-simplify the relationship between

sovereignty and subjectivity: a charge that William Connolly has also made.

Connolly advances a similar critique to Butler’s of Agamben’s account of the

logic of sovereignty.77 Connolly’s main objections are twofold. First, he argues that

Agamben naively and problematically assumes that there once was a separation

between zoē and bios: ‘What a joke [. . .] [e]very way of life involves the infusion

of norms, judgements, and standards into the affective life of participants at both

private and public levels’.78 While Connolly accepts the way in which ‘new

technologies of infusion’ have ‘intensified’ bio-political life, he maintains that ‘the

shift is not as radical as Agamben makes it out to be’.79 Second, according to

Connolly, Agamben’s answer to the problem of sovereignty is to simply transcend

it altogether by offering a diagnosis that is too elegant, cerebral, and convenient:

‘biocultural life exceeds any textbook logic because of the non-logical character of

its materiality [. . .] [it] is more messy, layered, and complex than any logical

analysis can capture’.80 Connolly thus arrives at the damning conclusion that

‘Agamben displays the hubris of academic intellectualism when he encloses political

culture within a tightly defined logic’.81

Running throughout Butler’s and Connolly’s criticisms of Agamben is an

understandable worry that his perspective ultimately closes off questions about

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

Butler, ‘Precarious Life’, p. 68.

Ibid., p. 68.

Ibid., p. 68.

W. Connolly, ‘The Complexity of Sovereignty’, in Edkins et al, Sovereign Lives.

Ibid., p. 28.

Ibid., p. 29.

Ibid., p. 29.

Ibid., p. 29.

The generalised bio-political border?

741

subjectivity, sovereignty, and politics more generally.82 At the heart of this critique

is a common complaint that the concept of bare life is too homogenising and

thus too simplistic to appreciate the detailed complexity of the production of

differentiated subjectivities. On the one hand, with its seemingly universalistic

pretensions, the notion of bare life might indeed appear too sweeping to allow

for nuanced analyses of subjectivity. On the other hand, I want to suggest, the

sting of this criticism is largely neutralised once the notion of bare life is untied

from the concept of zoē. If bare life is treated as precisely an indistinct form of

subjectivity that is produced immanently by sovereign power for sovereign power

then the true undecidability of the figure of homo sacer is brought into relief. This

move allows for a more differentiated approach to the production of subjectivities

under bio-political conditions because it does not fix bare life as some sort of

pre-given outside sovereignty. On this reformulation, bare life can be interpreted

as a form of subjectivity whose borders are always already rendered undecidable

by sovereign power; a form of subjectivity whose identity is always in question.

Therefore, a subjectivity whose inhabitation of a zone of indistinction requires

different modes of political analysis such as a ‘logic of the field’. Adopting a logic

of the field, with its privileging of analysis of the production of zones of

indistinction, does not only have implications for the way we consider the

production of subjectivities in world politics, however. Rather, Agamben’s work

opens up provocative lines of enquiry for thinking differently about the politics

of space and bordering practices.

Re-conceptualising the limits of sovereign power

While Agamben’s diagnoses of sovereign power, the generalised state of exception,

and bare life are all relatively well known in IR and related disciplines, the spatial

dimension of his work is perhaps the least explored.83 In many ways this is

surprising since Homo Sacer ends with the provocative claim that the contemporary bio-political nomos, which has seen the holy trinity of order, territory and

birth lapse into crisis, can only be diagnosed on the basis of the alternative spatial

register of a logic of the field: ‘Every attempt to rethink the political space of the

West must begin with the clear awareness that we no longer know anything of the

classical distinction between zoē and bios, between private life and political

existence, between man as a simple living being at home in the house and man’s

political existence in the city’.84 So, we might ask, what are the implications of this

conclusion for thinking about sovereign space and the construction of an

alternative border imaginary?

82

83

84

For examples of other attempted critiques of Agamben’s work along these lines see A. Neal, ‘Cutting

Off the King’s Head’ and A. Neal, ‘Foucault in Guantanamo’.

The notable exception here is the work of Political Geographer Claudio Minca. See C. Minca,

‘Agamben’s Geographies of Modernity’, Political Geography, 26:1 (2007), pp. 78–97; C. Minca,

‘Giorgio Agamben and the New Biopolitical Nomos’, Geografiska Annaler, 88B:4 (2006),

pp. 387–403; and C. Minca, ‘The Return of the Camp’, Progress in Human Geography, 29 (2005),

pp. 405–12.

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 187.

742

Nick Vaughan-Williams

Security as the normal technique of government

As we have already seen, Agamben’s approach to sovereignty is indebted to

Schmitt’s theory of the decision on the exception.85 Embellishing this theory of

sovereignty, however, Agamben invokes Benjamin’s critique of Schmitt in an

attempt to move the notion of the exception away from the issue of emergency

provisions towards a more relational and original function within the Western

political paradigm. In this way, for Agamben, Benjamin’s engagement with Schmitt

‘proves the necessary and, even today, indispensable premise of every inquiry into

sovereignty’.86

Schmitt’s theory of exception was in part attempting to neutralise Benjamin’s

concept of divine violence outside the law outlined in his 1921 essay, ‘Critique of

Violence’.87 Through the concept of the exception, Schmitt was able to show how

there is no pure violence outside the law: the exception is a mechanism by which

extra-legal operations can function as part of the juridical-political order. Yet, in

his ‘Eighth Thesis on the Concept of History’, Benjamin responded to Schmitt’s

theory of exception by arguing that, ‘the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that

the ‘state of exception’ in which we live is the rule’.88

According to Agamben, the ‘Eighth Thesis’ is the ‘decisive document in the

Benjamin-Schmitt dossier’ because it effectively ‘[puts] Schmitt’s thesis in check’.89

Benjamin’s counter-argument, while not dismissing Schmitt’s thesis entirely, points

to the way in which the Third Reich thrived on confusing the difference between

norm and exception, law and fact and order and anomie.90 It is precisely

Benjamin’s identification of the role of this confusion in the Nazi state that

inspires Agamben to attempt to then re-configure the activity of sovereign power

in terms of the creation of zones of indistinction: ‘the essential point [. . .] is that

a threshold of undecidability is produced at which factum and ius fade into each

other.’91

In his brief history of the state of exception, Agamben emplaces Benjamin’s

‘Eighth Thesis’ within a broader tradition of early twentieth century thought

dealing with the transformation of democratic regimes during the two world wars.

One of the cases Agamben draws upon is the post-1914 British legal system, which

witnessed the generalising of formerly exceptional measures within the state

apparatus. After Britain declared war on Germany the government asked

parliament to approve laws without debate. On 4 August 1914 the Defence of the

Realm Act (DORA) was passed giving the government powers to regulate the

economy and limit citizens’ rights. Later, parliamentary activity virtually ceased

altogether and on 29 October 1920 the Emergency Powers Act was introduced in

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

C. Schmitt, ‘Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty’, trans. G. Schwab,

3rd Edition (Chicago and London: the University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Ibid, p. 63.

W. Benjamin, ‘Critique of Violence’, in M. Bullock and M. Jennings (eds), Walter Benjamin: Selected

Writings Volume One 1913–1926 (Cambridge, MA and London: the Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press, 2004), pp. 236–52.

W. Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, in H. Eiland and M. Jennings (eds), Walter Benjamin:

Selected Writings, Volume 4, 1938–1940 (Cambridge, MA and London: The Bellknap Press of

Harvard University Press), p. 392.

Agamben, ‘State of Exception’, p. 58.

The Nazi state proclaimed a state of exception in 1933 but this was never repealed.

Agamben, ‘State of Exception’, p. 29.

The generalised bio-political border?

743

which Article One stated that: ’[. . .] His Majesty may, by proclamation [. . .],

declare that a state of emergency exists.92

For Agamben, Article One of the Emergency Powers Act constitutes a decisive

event in British legal history because it established the principle of the state of

exception within the juridical-political order. Since then, Agamben claims, ‘the

voluntary creation of a permanent state of emergency (though perhaps not declared

in the technical sense) has become one of the essential practices of contemporary

states, including so-called democratic ones’ like Britain.93 In other words, on

Agamben’s view, the state of exception (or ‘security’) has increasingly appeared as

what might be referred to as the ‘dominant paradigm of government in

contemporary politics’.94 In support of this view, which resembles something like

an ‘unstoppable global civil war’, Agamben refers to contemporary sovereign

practices that blur the otherwise taken-for-granted threshold between democracy

and absolutism.95 One example is President George W. Bush’s ‘Military Order’

authorising the ‘indefinite detention’ and ‘trial by military commissions’ of

non-citizens suspected of terrorist activities. This Order, justified with reference to

national security imperatives, works to secure sovereign power by removing the

legal and political status of a suspected individual thereby producing a ‘legally

unnameable and unclassifiable being’, as we have already seen.96

It is possible to identify something of a tension in Agamben’s account of the

history of the state of exception, which can be summarised as a question of

intensity or structure.97 On the one hand, Agamben sometimes talks about the

becoming-general of the state of exception in the West as if it were a gradual

turning of the screw since World War I, through fascism, to our current

situation.98 On the other hand, Agamben also emphasises on many more occasions

that the transformation of the state of exception into a paradigm of government

is not a modern innovation but a systemic feature of Western politics: it is the

constitutive paradigm of the juridical-political order.99 Agamben argues that the

years since World War I have seen the ‘testing and honing’ of this paradigm of

government that is in a fundamental sense an originary aspect of the juridicalpolitical life of Western societies.100 In other words, as Didier Bigo usefully puts

it, ‘the state of emergency in which we live is not an exceptional moment, limited

in object, space and time, but the norm, or more exactly it is the perpetuation of

the emergency as a rule, as a form of prolonged state of exception’.101

Some readers will no doubt be displeased with the apparent tension above,

although the extent to which one must choose between intensity or structure as if

they were mutually exclusive is debatable. If the production of bare life is not a

92

(Quoted in) Agamben, ‘The State of Exception’, p. 19.

Ibid., p. 2.

94

Ibid., p. 2.

95

Ibid., p. 2.

96

Ibid., p. 3.

97

I am indebted to one of the anonymous reviewers for this formulation and their critical commentary

on Agamben more generally.

98

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 4, p. 9; Agamben, ‘Means Without End’, p. 39; Agamben, ‘State of

Exception’, pp. 2–3.

99

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 6, p. 7, p. 8, p. 19, p. 28, p. 83; Agamben, ‘Means Without End’,

p. 37; Agamben, ‘State of Exception’, p. 3, pp. 6–7.

100

Ibid., p. 87.

101

D. Bigo, ‘The Ban the Pan and the Exception’, p. 5.

93

744

Nick Vaughan-Williams

new or particularly recent phenomenon, as Agamben maintains and illustrates with

reference to the figure of homo sacer in Roman law, then the exception must be

seen as a fundamental feature of Western politics. However, as I will go on to

argue, what has arguably changed within this over-arching framework is the

historically contingent character of both the method and location of the production

of bare life. In this way, reflecting Agamben’s commitment to a ‘logic of the field’,

it is also possible to read intensity and structure not as dichotomous but

fundamentally inter-related.

The generalised space of the exception

Agamben argues that what is at stake in the sovereign exception is the ‘creation

and definition of the very space in which the juridical-political order can have

validity’.102 He also claims, however, that such activity, which constitutes what

Schmitt calls the sovereign nomos,103 is not simply the taking of land but the taking

of an outside or exception. Borders, typically understood in terms of the

delimitation of sovereignty at the territorial outer-edge of the state, might be seen

as exceptional spaces on one reading: a zone of anomie excluded from the ‘normal’

juridical-political space of the state, but, nevertheless, an integral part of that space

(in fact the very condition of its possibility).104 Yet, for Agamben, the ‘constitutive

outside’ of sovereign territory is not a space that is localisable or to be found

literally at ‘the edge’ of the state in a geographical sense. Rather, Agamben sees

the constitutive outside as something fundamentally interior to the Western

bio-political juridical order.

According to Agamben, the constitutive outside of sovereign territory is the

generalised state of exception that brings together the otherwise separate realms of

law and life. The constitutive outside refers precisely to the sovereign decision on

the worthiness of life itself as belonging to either the citizen or bare life as its

ghostly shadow. As such, if we are to consider the spatiality of the constitutive

outside, it makes little sense to think of this as occupying a localised and static

terrain associated with traditional state borders. Instead, Agamben’s work prompts

a re-conceptualisation of the limits of sovereign power and a re-situation of the

constitutive outside of sovereign territory in a more generalised way. It is through

the inclusive exclusion of bare life, resting upon a decision about its status, that

sovereign power establishes its constitutive outside. Such a ‘decision’ is not

necessarily isolatable in space-time (though it can be), but rather simulated

throughout everyday life that places us all, virtually, under conditions of great

uncertainty.105 The generalisation of the space of exceptionalism is captured by

102

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, pp. 18–9.

C. Schmitt, ‘The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum’,

trans. G. Ulmen (New York: Telos Press, 2003).

104

See, for example, M. Salter, ‘The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the

International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 31:2 (2006),

pp. 167–89.

105

N. Vaughan-Williams, ‘Virtual Border (In)Security’, paper presented at the Annual Convention of

the International Studies Association, New York, February, 2009. See also F. Debrix, ‘Banning

Space: The Nomos of Exception and Virtual Territoriality’, paper presented at the Annual Meeting

of the American Association of Geographers, Las Vegas, March 2009.

103

The generalised bio-political border?

745

Agamben’s reference to the camp as ‘in some sense [. . .] the hidden matrix and

nomos of the political space in which we live’.106

Agamben refers to the emergence of concentration camps in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries, historically associated with the state of exception and martial

law, in order to illustrate how the simple dichotomies between inclusion and

exclusion, inside and outside, zoē and bios fail to hold in the final analysis. For

Agamben, the space of the camp is fundamentally paradoxical: ‘the camp is a piece

of territory that is placed outside the normal juridical order’ and yet ‘it is not

simply an external space’.107 The camp excludes what is captured inside, which, as

an inclusive exclusion, blurs conventional spatial distinctions such as those above.

Because law is suspended in the camp and arbitrary or exceptional decisions on the

status of life become the rule, Agamben argues that the camp represents: ‘the most

absolute bio-political space that has ever been realised – a space in which power

confronts nothing other than pure biological life without any mediation’.108 As

such, people in camps, as we have seen in the context of Guantánamo, ‘move

about in a zone of indistinction between the outside and the inside, the exception

and the rule, the licit and the illicit’.109

To some extent the camp is another figure that is characterised somewhat

ambiguously in Agamben’s work. The camp can be read as a historically

contingent manifestation of the operations of sovereign power: ‘the space that

opens up when the state of exception starts to become the rule’.110 However, for

Agamben the camp is not understood as an anomaly or merely a historical fact.111

Rather, he argues that the camp is itself a structure: ‘if sovereign power is founded

in the ability to decide on the state of exception, the camp is the structure in which

the state of exception is permanently realised’.112 On this basis, Agamben claims

that the camp reveals something fundamental to the Western paradigm born of the

exception: the attempt to materialise the state of exception and create a space in

which bare life and juridical rule enter into a threshold of indistinction.113 Thus,

even if President Barack Obama succeeds in his stated intention to close the

detention camp at Guantánamo Bay by January 2010, the fundamental biopolitical structure of which it is symptomatic would for Agamben persist and

simply be manifested elsewhere.

The generalised bio-political border?

On the one hand, the production of bare life in zones of indistinction is most

visible in contemporary camps specifically designated for that purpose (not only

Guantánamo, but, for example: Bagram and Kandahar air bases in Afghanistan;

Abu Ghraib and Camp Bucca in Iraq; the Baxter immigration facility in Southern

106

Agamben, Means Without End, p. 37.

Ibid., p. 40.

108

Ibid., p. 41.

109

Ibid., pp. 40–1.

110

Ibid., p. 39.

111

Ibid., p. 37.

112

Ibid., p. 40.

113

Ibid., pp. 171–2.

107

746

Nick Vaughan-Williams

Australia; the new Sodhexo-run detention centre near Heathrow; and various

so-called CIA ‘black sites’ in Eastern Europe). At these sites, as I have shown

against the backdrop of Guantánamo, exceptional practices have become routine

and bare life is produced through the blurring of zoē and bios.

On the other hand, Agamben draws attention to the way in which the

production of zones of indistinction, where exceptional activities become the rule,

is more and more widespread in global politics. Indeed, the notion of the

generalised space of exception points to the way in which characteristics usually

associated with the edges, margins, or outer-lying areas of sovereign space

gradually blur with what is conventionally taken to be the ‘normality’ of that

space. Whereas the space of the exception was once localised in spaces such as the

camps, Agamben implies that in more recent times it has become increasingly

generalised in contemporary political life: ‘the camp, which is now firmly settled

inside [the nation-state], is the new bio-political nomos of the planet’.114

In Homo Sacer Agamben refers to zones d’attentes in French airports (where

foreigners seeking refugee status are detained) as an example of the way in which

the structure of the camp permeates everyday life: ‘in [. . .] these cases, an

apparently innocuous space in which the normal order is de facto suspended and

in which whether or not the atrocities are committed depends not on law but the

civility and ethical sense of the police who temporarily act as sovereign’.115 Under

bio-political conditions in which ‘the paradigm of security has become the normal

technique of government’, Agamben argues that we can no longer rigorously

distinguish our biological life as living beings from our political existence.116 In this

way, as Claudio Minca has put it, there has been a ‘normalisation of a series of

geographies of exceptionalism in Western societies’.117

Agamben’s central thesis, that the structure of the camp is the ‘hidden matrix

and nomos of the political space in which we live’, calls for a reconsideration of

what and where borders in contemporary political life might be. Instead of viewing

the limits of sovereign power as spatially fixed at the outer-edge of the state,

Agamben reconceptualises those limits in terms of a decision or speech act about

whether certain life is worthy of living or life that is expendable. Such a decision

performatively produces and secures the borders of sovereign community as the

politically qualified life of the citizen is defined against the bare life of homo sacer.

The concept of the border of the state is substituted by the sovereign decision to

produce some life as bare life: it is precisely this dividing practice, one that

can effectively happen anywhere, that constitutes the ‘original spatialisation of

sovereign power’.118 Such a decision is very much a practice of security because the

production of bare life shores up notions of who and what ‘we’ are.

Although Agamben does not refer to it in his work, one way of capturing the

alternative border imaginary he proposes is in terms of what I want to call the

‘generalised bio-political border’. This concept refers to the global archipelago of

zones of indistinction in which sovereign power produces the bare life it needs to

sustain itself and notions of sovereign community. Here, following Eyal Weizman,

114

Ibid., p. 45.

Ibid., p. 174.

116

Ibid., p. 39.

117

Minca, ‘Giorgio Agamben and the New Biopolitical Nomos’, p. 388.

118

Ibid., p. 388.

115

The generalised bio-political border?

747

the concept of the ‘archipelago’ is used to refer to ‘the spatial expression of a series

of ‘states of emergency’, or states of exception that are either created through the

process of law (through which law is in fact severely undermined or annulled) or

that appear de facto within them’.119 Thinking in terms of the generalised

bio-political border unties an analysis of the activity of sovereign power from the

territorial limits of the state and relocates such an analysis in the context of a

bio-political field spanning domestic and international space. As such it reflects

Balibar’s observation that borders are being ‘thinned out and doubled, [. . .] no

longer the shores of politics but [. . .] the space of the political itself’.120

By way of illustration, the dynamics of the generalised bio-political border can

be seen to be at play in two episodes of the ‘war on terror’ in the UK: the case

of the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes on 22 July 2005 and the Forest Gate

raids on 2 June 2006.

In the immediate hunt for those behind the so-called ‘failed’ bombings in

London on 21 July 2005, UK anti-terrorist officers killed Jean Charles de Menezes

the following day onboard an underground train at Stockwell station, South

London.121 The shooting was an arbitrary decision on the status of life. Crucially,

however, in the light of my overall argument, it was an arbitrary decision that did

not occur in a particular zone or space designated for exceptional practices. On the

contrary, the shooting took place within what is usually considered to be the

‘normal’ juridical-political space of the state. Yet, Menezes, a Brazillian citizen

working in the UK, was produced as bare life within the ‘normal’ space: not

safeguarded by the rule of law but subjected to the whims of CO19 who, as

temporary sovereigns, assessed his description and demeanour, considered his

identity to be that of a bomber suspect, and concluded his annihilation would not

constitute a crime. In this case, Menezes had effectively been banned from – or

rather abandoned by – the law: ‘exposed and threatened on the threshold in which

life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguishable’.122

As I have argued elsewhere, the Menezes shooting provides an illustration of

the way in which bare life is not a form of life into which one is somehow born.123

Rather, since Menezes was a Brazilian citizen, his case demonstrates how sovereign

power works to produce bare life immanently: temporary sovereigns rendered his

life ‘bare’. Furthermore, the shooting can also be read as adding credence to

Agamben’s claim otherwise seemingly sensationalist claim that ‘we are all

(virtually) homines sacri’.

Similar dynamics reflective of the generalised bio-political border are illustrated

by the Forest Gate raids in East London. On 2 June 2006, 250 police officers

surrounded 46–48 Lansdowne Road in the Forest Gate area of London on

suspicion that a chemical bomb had been hidden in the property.124 At 4am, the

119

E. Weizman, ‘On Extraterritoriality’, in G. Agamben et al (eds), Arxipèlag D’Excepcions: Sobiranies

de l’extraterritorialitat (Barcelona: Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona: 2007), p. 13.

Balibar, ‘The Borders of Europe’ (1998), p. 220.

121

BBC News Report, Menezes death a ‘state execution’, 19 September 2005, {http://news.bbc.co.uk/

1/hi/uk_politics/4261136.stm}

122

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 29.

123

For further elaboration of my argument on the shooting of Menezes in this context see N.

Vaughan-Williams, ‘The Shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes: New Border Politics?’ Alternatives:

Global, Local, Political, 32:2 (June 2007), pp. 177–95.

124

Account given by BBC news website, {http://bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/5075952.stm} accessed on 14 June 2006.

120

748

Nick Vaughan-Williams

Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist Squad raided the house and, without any

warning and at close range, shot a suspect in the chest, narrowly missing his

heart.125 The injured man was identified as Mohammed Abdul Kahan and he was

rushed immediately to hospital, while another man, Kahan’s brother Abdul

Koyair, was taken to Paddington Green High Security Prison. Under the

Terrorism Act 2000, both men were detained for a week for further questioning

despite having not been charged with any specific offence according to their

solicitor.126

What these events demonstrate is the way in which sovereign power blurs the

traditional distinction between zoē and bios so that, as Agamben remarks in Homo

Sacer: ‘we no longer know anything of the classical distinction between [. . .] private

life and political existence, between man as a simple living being at home in the house

and man’s political existence in the city’.127 As such, whereas the Menezes case

illustrates the difficulty of upholding any rigorous distinction between ‘normal’ and

‘exceptional’ space, the Forest Gate raid takes the illustration of Agamben’s

argument further by showing how the home itself offers little refuge from the

sovereign operation.

The scenes at Stockwell tube station and Lansdowne Road respectively

resembled what might be conventionally, though perhaps not exclusively, associated with a border site: a heavy police presence; the use of exceptional measures;

shootings legitimised by an emergency situation and national security imperatives.

Both episodes took place in what is ordinarily considered to be the ‘normal’ space

of the state, however, not an ‘exceptional’ space on its margins, outer-edges, or

peripheries. In both cases sovereign power produced bare life caught in a zone of

indistinction between zoē and bios.

Although the character and outcome of the shooting of Menezes and the Forest

Gate raids are different in some important respects, Agamben’s portrayal of the

logic of sovereign power is common to both. They also indicate that, if the

production of bare life in zones of indistinction constitutes the limits of sovereign

power, those limits are not necessarily coterminous with the territorial borders of

the state. On the contrary, the concept of the generalised bio-political border

enjoins us to rethink ‘the border’ as a far more complex and differentiated site than

that portrayed by the traditional geopolitical imagination.

Conclusion: re-thinking the border in IR and security studies

The concept of the border of the state has acted, and continues to act, as a lodestar

in the theory and practice of global politics. Yet, as Balibar and others have sought

to point out, it is possible to identify how, under current global conditions, ‘the

border’ has become an increasingly complex, differentiated, and dispersed array of

practices. Instead of being solely fixed at the territorial outer-edge of the state, as

125

According to police shooting guidelines officers can shoot ‘to stop an imminent threat to life’.

However, firearms officers must identify themselves and give oral warnings of their intent to shoot.

Shots are only to be fired in the ‘most serious and exceptional circumstances’. See {http://bbc.co.

uk/1/hi/uk/5042724.stm.}

126

Account given by BBC news website, {http://bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/5075952.stm} accessed on 14 June 2006.

127

Agamben, ‘Homo Sacer’, p. 187 (Emphasis added).

The generalised bio-political border?

749

represented by the dominant modern geopolitical imagination, borders are

evermore electronic, invisible, and mobile. Despite the increasing sophistication of

diverse bordering practices, however, there is a sense in which border thinking

within IR, security studies, and related disciplines, continues to lag behind. This lag

is detectable in at least two senses: first, in terms of the somewhat limited range of

concepts, metaphors, and vocabularies available to talk about the possibility of

empirical shifts in the nature of ‘the border’; second, in the sense that much of the