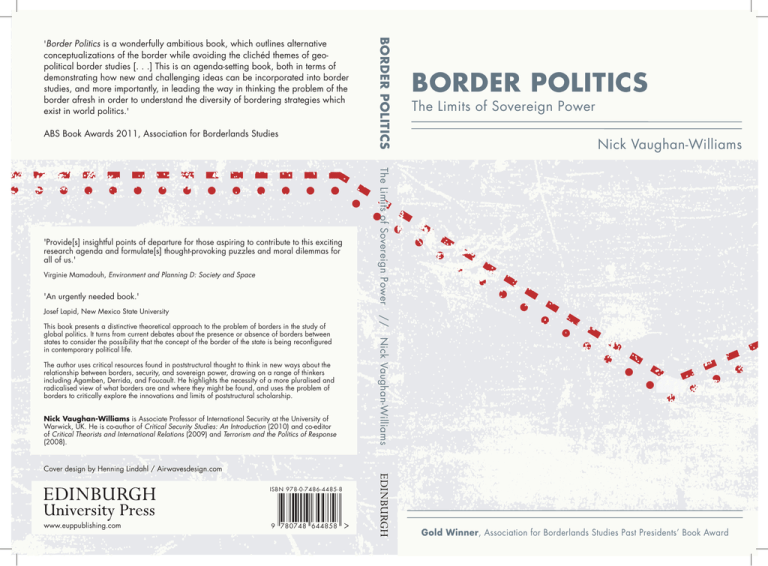

BORDER POLITICS

advertisement

conceptualizations of the border while avoiding the clichéd themes of geopolitical border studies [. . .] This is an agenda-setting book, both in terms of demonstrating how new and challenging ideas can be incorporated into border studies, and more importantly, in leading the way in thinking the problem of the border afresh in order to understand the diversity of bordering strategies which exist in world politics.' ABS Book Awards 2011, Association for Borderlands Studies Virginie Mamadouh, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 'An urgently needed book.' The author uses critical resources found in poststructural thought to think in new ways about the relationship between borders, security, and sovereign power, drawing on a range of thinkers including Agamben, Derrida, and Foucault. He highlights the necessity of a more pluralised and radicalised view of what borders are and where they might be found, and uses the problem of borders to critically explore the innovations and limits of poststructural scholarship. Nick Vaughan-Williams is Associate Professor of International Security at the University of Warwick, UK. He is co-author of Critical Security Studies: An Introduction (2010) and co-editor of Critical Theorists and International Relations (2009) and Terrorism and the Politics of Response (2008). Nick Vaughan-Williams Nick Vaughan-Williams This book presents a distinctive theoretical approach to the problem of borders in the study of global politics. It turns from current debates about the presence or absence of borders between states to consider the possibility that the concept of the border of the state is being reconfigured in contemporary political life. The Limits of Sovereign Power // Josef Lapid, New Mexico State University BORDER POLITICS The Limits of Sovereign Power 'Provide[s] insightful points of departure for those aspiring to contribute to this exciting research agenda and formulate[s] thought-provoking puzzles and moral dilemmas for all of us.' BORDER POLITICS 'Border Politics is a wonderfully ambitious book, which outlines alternative Cover design by Henning Lindahl / Airwavesdesign.com ISBN 978-0-7486-4485-8 www.euppublishing.com 9 780748 644858 Gold Winner, Association for Borderlands Studies Past Presidents’ Book Award 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page i BORDER POLITICS 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page ii 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page iii BORDER POLITICS The Limits of Sovereign Power Nick Vaughan-Williams 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page iv For Ning © Nick Vaughan-Williams, 2009, 2012 First published in hardback in 2009 by Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com This paperback edition 2012 Typeset in Palatino Light by Norman Tilley Graphics Ltd, Northampton, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4485 8 (paperback) The right of Nick Vaughan-Williams to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page v CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction The concept of the border of the state in contemporary political life A blind spot in International Relations theory? The vacillation of borders The quest for alternative border imaginaries Map of the book 1 Borders are Not What or Where They are Supposed to Be: Security, Territory, Law Borders and security: the United Kingdom’s ‘new’ border doctrine Borders and territory: the European Union and the rise of Frontex Borders and law: the United States’ naval base in Guantánamo Bay The need to rethink what and where borders are 2 The Study of Borders in Global Politics: From Geopolitics to Biopolitics Limology: a brief history and current ‘state of the art’ Assuming the concept of the border of the state Acknowledging the concept of the border of the state Further problematising the concept of the border of the state vii 1 2 4 6 8 10 14 16 24 29 32 38 40 44 47 51 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics vi 29/11/11 16:09 Page vi BORDER POLITICS 3 Violence, Territory and the Borders of Juridical–Political Order: Problematising the Limits of Sovereign Power Walter Benjamin and Jacques Derrida: cartographies of violence Carl Schmitt: sovereignty, territory, limits Michel Foucault: the ‘how’ of power Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri: the smooth space of Empire 4 The Generalised Biopolitical Border: Security as the Normal Technique of Government Politics, life, and sovereign power Reconceptualising the limits of sovereign power Generalised border politics: the case of the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes 65 66 72 77 83 96 97 108 117 5 Alternative Border Imaginaries: The Politics of Framing Thinking in terms of the generalised biopolitical border Ethical–political implications of the generalised biopolitical border The politics of framing 130 132 Conclusion 163 Bibliography Index 171 185 136 146 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express my gratitude to the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW) Centre for Border Studies at the University of Glamorgan for the Research Studentship that funded the PhD thesis on which this book is based; the Department of International Politics, University of Wales, Aberystwyth (now Aberystwyth University), and the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, for providing an intellectually challenging yet supportive environment in which to work on the original thesis; and more recently the Department of Politics, University of Exeter, for enabling me to complete the project in final book form. Additionally, I wish to acknowledge the following colleagues, mentors and friends. At Aberystwyth I enjoyed four years as both a doctoral student and temporary Lecturer in International Theory and Security. I would like to thank: Jenny Edkins, for belief in me and the thesis, inimitable good humour and company, and outstanding qualities as a supervisor, mentor, and confidante; Hidemi Suganami, for taking me on as a supervisee somewhat late in the day, and never ceasing to challenge and provoke (and talk about causation); Colin McInnes, for supervisory support in the formative stages of the thesis and professional advice and encouragement as Head of Department; Andrew Linklater, who acted as my internal examiner and provided helpful feedback and advice; Tom Lundborg, for valued discussions and friendship in Aber and for introducing me to the ‘dark precursor’; Cian O’Driscoll for promenade-based pursuits and engaging, though usually just-war-based, conversation; and Columba Peoples for showing us all how it should be done. Outside Aberystwyth, I owe a huge debt to: R. B. J. Walker, for his comments on my thesis as external examiner and intellectual and professional generosity since the viva; Maja Zehfuss, for introducing me to Jacques Derrida, inspiring me to vii 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics viii 29/11/11 16:09 Page viii BORDER POLITICS pursue doctoral research, and persuading me that life in West Wales wouldn’t be that bad; Noel Parker, for friendship and intellectual comradeship in Copenhagen and beyond; and James Brassett, Dan Bulley, Angharad Closs Stephens, Debbie Lisle, Luis Lobo-Guerrero, Andrew Neal, Mustapha K. Pasha, Rens van Munster, and Chris Rumford for their ideas, collegiality, and friendship. Most recently, I have been exceptionally lucky to have found some excellent colleagues at the University of Exeter, who offer an enviable intellectual context and a lively social scene in equal measure. Particular thanks are extended to: Tim Cooper, Michael Delashmutt, Tim Dunne, Robin Durie, Jonathan Githens-Mazer, John Heathershaw, Bice Maiguashca, Alex Murray, Andy Schaap, Dan Stevens, and Colin Wight. Also, I must express my appreciation to Rory Carson, Ollie Deakin, and Owen Rawlings for reminding me from time to time that life does exist beyond academia. The transition to academic life over the past ten years would not have been possible without the unstinting support of my family. Thanks are due to my mother and father, and especially to my grandmother to whom this book is dedicated, for their unconditional love: they are my backbone and I suspect they do not know how much I value them. I especially want to thank Madeleine for her patience and understanding while I was working on the book, her compassionate and intelligent companionship, and most importantly our relationship. There are also a number of people who have made this book possible in a more practical sense. I wish to express my thanks to: John Williams and Yosef Lapid for providing constructive feedback on draft chapters and their generous support of the book; two other anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript; Nicola Ramsey, Senior Commissioning Editor at Edinburgh University Press, for her outstanding support and lightness of touch in seeing this project through to completion; Neil Curtis for his fastidious attention to detail in the copy-editing process; and Henning Lindahl for his characteristically excellent work on the jacket design. Finally, parts of the book have appeared elsewhere at earlier stages in the project and I would like to acknowledge these publications as follows. The discussion of Frontex in Chapter 1 was originally developed in an article I published as ‘Borderwork beyond inside/ outside? Frontex, the Citizen-Detective, and the War on Terror’, Space 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics Acknowledgements 29/11/11 16:09 Page ix ix and Polity, 12 (1), (April 2008), pp. 63–79. Elements of Chapter 3 were published as ‘Borders, Territory, Law’, International Political Sociology, 4 (2) (December, 2008), pp. 322–38. My treatment of the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in Chapter 4 is an abridged version of the article ‘The Shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes: New Border Politics?’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 32 (2) (April–June 2007), pp. 177–96, which also appears in A. Closs Stephens and N. VaughanWilliams (eds), Terrorism and the Politics of Response (Abingdon and New York: Routledge). Finally, parts of the exegesis of the work of Jacques Derrida at the end of Chapter 5 are based on a section in my article ‘International Relations and the “Problem of History”’, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 34 (1), (2005), pp. 115–36. I am also grateful to Thales International and to the London Metropolitan Police for permission to reproduce Figures 1 and 3. Falmouth September 2008 01 pages i-x prelims:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:09 Page x 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:07 Page 1 INTRODUCTION Borders are ubiquitous in political life. Indeed, borders are perhaps even constitutive of political life. Borders are inherent to logics of inside and outside, practices of inclusion and exclusion, and questions about identity and difference. Of course, there are many different types of borders that can be identified: divisions along ethnic, national or racial lines; class-based forms of stratification; regional and geographical differences; religious, cultural, and generational boundaries; and so on. None of these borders is in any sense given but (re)produced through modes of affirmation and contestation and is, above all, lived. In other words borders are not natural, neutral nor static but historically contingent, politically charged, dynamic phenomena that first and foremost involve people and their everyday lives. Ostensibly, this book focuses upon one particular type of border: the concept of the border of the state. I say ‘ostensibly’ because, as I hope will become obvious, different types of borders inevitably fold into one another: the notion of maintaining sharp, contiguous distinctions between anything is impossible and inevitably breaks down. In a common understanding of the term, the concept of the border of the state refers to ‘external’, ‘interstate’ or ‘international’ borders that delimit and delineate states as independent entities in the state system.1 According to what John Agnew has referred to as the ‘modern geopolitical imaginary’, state borders are taken to be territorial markers of the limits of sovereign political authority and jurisdiction, and located at the geographical outer edge of the polity.2 Accompanying this imaginary is a well-known historical account of the emergence and supposed ossification of such borders associated with the transition from overlapping jurisdictions in medieval Europe to the emergence of the modern sovereign state characterised by strict 1 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 2 29/11/11 16:07 Page 2 BORDER POLITICS territorial delimitations.3 Irrespective of conceptual or historical accuracy, there is little doubt that this imaginary, underpinned by the concept of the border of the state, has had, and indeed continues to have, significant political and ethical influence on the practice and theory of global politics. THE CONCEPT OF THE BORDER OF THE STATE IN CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL LIFE Like all concepts in the practice/theory of global politics, the concept of the border of the state is politically and ethically charged: its usage in all kinds of discourses must be seen as in part constituting the modern geopolitical imaginary it purports merely to describe.4 One obvious example of the work that the concept of the border of the state does is to allow for a familiar spatial and temporal compartmentalisation of global politics into two supposedly distinct spheres of activity: history and progress inside, and timeless anarchy outside.5 In turn, such a compartmentalisation permits a problematic division of labour between scholars of politics on the one hand and international relations on the other.6 It is clear that the concept of the border of the state does a lot of work, epistemologically and ontologically, in shaping thinking about diverse issues in global politics. The concept of the border of the state underpins the arrangement of, and indeed the very condition of possibility for, both domestic and international legal and political systems. Domestically, it is integral to conventional notions of the limits of internal sovereignty and authority, reflected in Max Weber’s paradigmatic definition of the state as: ‘a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of force within a given territory’.7 In the international sphere it enables the principle of territorial integrity, enshrined in Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the United Nations (UN) Charter which, since the end of World War II, has acted as the cornerstone for regulative ideals such as: the legal existence and equality of all states before international law; protection against the promotion of secessionism by some states in other states’ territory; and territorial independence and preservation.8 As such, and despite historical and contemporary examples of derogations of these regulative ideals, without the notion of territorial integrity reliant upon the concept of the border of the state there would simply be no ‘domestic’ 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics Introduction 29/11/11 16:07 Page 3 3 and ‘international’ juridical–political orders to speak of in the first place. As a central feature of the architecture of global politics, the concept of the border of the state can be thought of as a sort of compass. It orients the convergence of people with a given territory and notions of a common history, nationality, identity, language and culture. In this way, it is a pivotal concept that opens up – but can also close down – a multitude of political and ethical possibilities. Not only does this particular border delimit states but also different forms of subjectivity or ‘personhood’ that are produced by the domestic/international juridical-political order. Like the modern sovereign state, the modern political subject is also conceived of as being fundamentally bordered in terms of autonomy before the law.9 Hence, discourses of rights and responsibilities presume the subject of contemporary political life to be an individual whose status is clearly demarcated: a citizen. Seen in these terms, the concept of the border of the state is central to the production of citizen-subjects whose identity derived from citizenship provides a series of convenient answers to difficult questions such as Who am I? Where do I belong? What should I do? The concept of the border of the state has also framed the way global security relations are commonly conceptualised. Although the study of security is a fundamentally contested terrain, the modern geopolitical imaginary has had a bearing on the trajectory of the field. This influence has been especially, though not exclusively, due to the relative dominance of realist and neo-realist approaches in security studies. Such approaches, with their emphasis on states’ survival in an anarchical self-help system, rely on the concept of the border of the state in order to frame their reading of the key elements of security: the referent object of the threat (national security); the source of the threat (other states in the context of anarchy); and the likely means of overcoming that threat (interstate warfare). Indeed, the concept of the border of the state frames dominant notions of who and where the ‘enemy’ of the state is. As has been pointed out elsewhere, realist and neo-realist perspectives understand security in terms of the history of the defence and/or transgression of states’ borders.10 Although the insights of this approach have been questioned over recent years, particularly so since the end of the Cold War, aspects of such thinking undoubtedly continue to permeate security practices. Indeed, the rise of the notion of ‘homeland security’ in the context of Western governments’ attempts to counter the threat of international terrorism 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 4 29/11/11 16:07 Page 4 BORDER POLITICS has led to a reinvigoration of border protection initiatives: ‘the new age of the wall has begun’, writes Guardian columnist Julian Borger, ‘ramparts and stone fortifications, regarded until recently as national relics and tourist attractions, are back with a vengeance’.11 A BLINDSPOT IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THEORY? Despite the ubiquity of borders in political life, and the particularly privileged position of the concept of the border of the state, a number of writers with very different perspectives have bemoaned what they consider to be the paucity of reflection on these matters in the theoretical literature produced by the discipline of International Relations (IR). For Chris Brown, ‘neither modern political theory nor IR theory has an impressive record when it comes to theorising the problems caused by borders’.12 Similarly, Robert Jackson has argued that: ‘it is remarkable that state borders are usually taken for granted by international relations. They are a point of departure but they are not a subject of inquiry.’ 13 Others in IR who have written in a similar vein include Mathias Albert,14 Yosef Lapid,15 Andrew Linklater and John MacMillan,16 R. B. J. Walker,17 and John Williams.18 Similar complaints have been made about the strange absence of theoretical reflection on the role of borders in political life in a number of other disciplinary contexts such as political anthropology,19 political sociology,20 and political geography.21 Williams neatly sums up the basic point made by all these writers: that borders between states are all too often treated as if they were merely the ‘fixtures and fittings’ of the international system.22 One of the purposes of this book is to contribute to efforts to address this deficiency within the extant literature. My motivation to write, however, is not only framed by what has hitherto remained unsaid about borders. It also stems from a dissatisfaction with what I consider to be the largely unreflective usage of the concept of the border of the state in diverse claims about global politics. In this context it is possible to identify two basic, prominent and competing discourses: the first is the claim that borders between states are a thing of the past; the second is the assertion that borders between states are here to stay. According to the first discourse, the transformation of global 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics Introduction 29/11/11 16:07 Page 5 5 production, involving the growth of multinational companies, a twenty-four hour market and post-Fordist industries, has rendered the notion of a national economy obsolete.23 On this view, economic change is said to have ushered in new patterns of governance, in which the role of the modern, sovereign, territorially bordered state has also diminished.24 The emergence of the European Union, with its self-portrayal as a ‘borderless area of freedom, security and justice’, could be cited as an example of this transformation. Consequently, it is sometimes argued that the erosion of state borders over recent decades threatens the very idea of the Westphalian territorially defined international state system.25 By contrast, the second discourse maintains that national economies have been left intact if not actually strengthened by globalisation.26 According to this perspective, the modern state continues to remain the primary political entity in world politics.27 Moreover, especially since the attacks on the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001, there have been challenges to the concept of globalisation and discourses relating to borderlessness.28 In the face of mounting American military aggression, and various reassertions of territorial sovereignty, some writers, as we have already seen, argue that state borders are more important than ever.29 Despite the fact that an array of evidence can be collected and mounted in defence of both positions, by now the above debate has reached something of an impasse. This implies the need for an alternative approach that does not reify the contours of the debate by simply arguing in favour of one side over the other. How might this be done? A preliminary and very straightforward observation concerning the debate is that, despite the apparent irreconcilability of the two competing discourses, both rely upon a particular understanding of the concept of the border of the state. This understanding not only reflects, but works within and further entrenches, the modern geopolitical imaginary. What the debate excludes is precisely the possibility that the concept of the border of the state has undergone transformation in contemporary political life. A focus on whether borders between states are merely ‘present’ or ‘absent’ is blind to dynamics in political practices that challenge the very imaginary within which those claims about ‘presence’ or ‘absence’ are able to make any sense at all. 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 6 29/11/11 16:07 Page 6 BORDER POLITICS THE VACILLATION OF BORDERS Étienne Balibar has written about the way in which borders in contemporary political life are not necessarily where they are supposed to be according to the modern geopolitical imaginary: ‘We are living in a conjecture of the vacillation of borders – both of their layout and function – that is at the same time a vacillation of the very notion of the border, which has become particularly equivocal.’ 30 The significance of Balibar’s argument, especially when related back to the impasse of the debate above, is that the vacillation of borders is not conflated with their disappearance. On the contrary, for Balibar borders are being ‘multiplied and reduced in their localisation, […] thinned out and doubled, […] no longer the shores of politics but […] the space of the political itself’.31 As such, Balibar offers a provocative starting point for engaging with the debate about the presence/ absence of borders between states without reifying either side. Instead, he implies the need to think more imaginatively, and perhaps even outside the modern geopolitical imaginary, to begin to grasp what is going on in global politics: ‘borders […] are no longer at the border, an institutionalised site that could be materialised on the ground and inscribed on the map, where one sovereignty ends and another begins’.32 In this context, it is difficult to overstate the enormity of what is at stake, conceptually, historically and politically, in Balibar’s seemingly paradoxical formulation that ‘borders are no longer at the border’. The notion that both the nature and location of borders have undergone some sort of transformation requires a quantum leap in the way we think about bordering practices and their effects. It also radically challenges the kinds of orientation hitherto provided by the modern geopolitical imaginary underpinned by the concept of the border of the state. In turn, this raises particularly difficult questions about how issues relating to juridical–political order, citizenship, subjectivity, identity, security and so on might be framed otherwise. Thus, Balibar’s pithy formulation highlights an urgent need for the development of alternative border imaginaries apposite to the study of the changes he diagnoses. In his call for generating different ways of conceptualising borders, Balibar is certainly not alone. Rather, it is possible to identify similar concerns expressed by a number of writers working with various 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:07 Page 7 Introduction 7 perspectives from diverse disciplinary backgrounds. For example, R. B. J. Walker, who has systematically interrogated the logic of inside/ outside upon which the modern geopolitical imaginary underpinned by the concept of the border of the state rests, issues a similar injunction to Balibar throughout many of his texts.33 Walker argues that: ‘We have shifted rather quickly from the monstrous edifice of the Berlin Wall, perhaps the paradigm of a securitized territoriality, to a war on terrorism, and to forms of securitization, enacted anywhere.’ 34 Likewise, Achille Mbembe has insisted: ‘[I]n [the] heteronymous organisation of territorial rights and claims, it makes little sense to insist on distinctions between “internal” and “external” political realms, separated by clearly demarcated boundaries.’ 35 In the same vein, Eyal Weizman writes: ‘New and suggestive cartographic representations of today’s world [are required] […] a departure from the traditional view of a world that consists of a series of more or less homogenous [sic] nation states separated by clear borders in a continuous spatial flow.’ 36 Moreover, albeit in different ways and contexts, many other writers have made equivalent claims about the need for alternative border imaginaries in the study of global politics, including Didier Bigo,37 David Campbell,38 Zaki Laïdi,39 Yosef Lapid,40 Noel Parker,41 Chris Rumford,42 Gearóid Ó Tuathail and Simon Dalby,43 Michael J. Shapiro,44 and William Walters.45 Yet, despite these repeated calls, there has been a noticeable reticence when it comes to the task of conceptualising such alternative border imaginaries and then putting them to work against different backdrops. As Walker has argued, this reticence is perhaps unsurprising given the stakes involved: Better explanations – of contemporary political life – are no doubt called for, but they are unlikely to emerge without a more sustained reconsideration of fundamental theoretical and philosophical assumptions than can be found in most of the literature on international relations theory.46 Nevertheless, there is a real danger of a growing disjuncture between the increasing complexity and differentiation of borders in global politics on the one hand, and yet the apparent simplicity and lack of imagination with which borders and bordering practices continue to be treated on the other. This raises the fundamental question: How 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 8 29/11/11 16:07 Page 8 BORDER POLITICS might it be possible to develop alternative conceptualisations of borders without reproducing the modern geopolitical imaginary? THE QUEST FOR ALTERNATIVE BORDER IMAGINARIES This book responds to the challenge issued by Balibar, Walker, Mbembe, Weizman and others to develop alternative border imaginaries. To address the central question above the analysis steps outside the literature in IR and related disciplines and draws upon hitherto largely untapped resources for extended thinking about the problem of borders found in post-structuralist thought. The term ‘post-structuralism’ is highly problematical and it is with hesitation that I use it throughout as a heuristic device to refer to a heterogeneous body of social, political, and philosophical work. Indeed, one of the many problems with the term is that some of the authors whose work is often labelled as ‘post-structural’ simply do not subscribe to or even recognise it as an approach.47 Nevertheless, with these necessary caveats in mind, I will argue that the thinkers under consideration, primarily Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, are particularly apposite to the task in hand because they all share a common interest in critically questioning both the logic and practice of borders in a general sense. By this I mean that an area of overlap between them is an insistence on detailed analyses of how different entities, such as concepts, subjects, communities and, indeed, states, become produced as separate phenomena to begin with. In other words, rather than taking such entities as somehow distinct from the outset and then merely analysing the relationships between them, attention is drawn to their production as supposedly singular entities in the first place.48 Moreover, as subsequent discussions will seek to illuminate, this prior move to produce entities as distinct relates intimately to questions about force, violence, power, authority and legitimacy, thus necessitating interrogation in its own right. On this basis, it is precisely how borders work – and how they might be identified, interrogated and sometimes resisted – that is of central concern to the thinkers I have chosen to focus upon. From this general theoretical starting point, the insights of the authors above are used initially to problematise the concept of the border of the state. Here the use of the term ‘problematisation’ relates 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics Introduction 29/11/11 16:07 Page 9 9 to the method Foucault developed in his various studies of madness, sexuality, discipline, and surveillance and other aspects of social and political life.49 Instead of asking questions like ‘What is madness?’ Foucault was more interested in exploring how different understandings of madness change over time through an analysis of the field of relations around the concept.50 As a method, problematisation interrogates the way that a concept is used in discourse, how that usage is connected to questions to do with power relations, and the way in which it is also productive of particular forms of subjectivity. Therefore, rather than ask ‘What is the concept of the border of the state?’, my analysis draws upon the insights of Agamben, Foucault and Derrida together with other thinkers, such as Walter Benjamin and Carl Schmitt, to think about the work that this concept does: that is to say what is enabled, constrained or even concealed by the modern geopolitical imaginary it underpins and sustains. In particular, the analysis seeks to consider the relationship between the concept of the border of the state and our understanding of practices of sovereignty, violence and (bio)power in contemporary political life. As well as problematising the concept of the border of the state, however, the book also draws on the above thinkers in search of critical resources for developing alternative border imaginaries. In this regard, the move from a geopolitical to a biopolitical horizon of thinking, initially inspired by Foucault and then taken in new and provocative directions by Agamben, opens up crucial lines of enquiry. I argue that much promise is to be found in Agamben’s oeuvre for a reconceptualisation of the limits of sovereign power: not as fixed territorial borders located at the outer edge of the state but rather infused through bodies and diffused throughout everyday life. On the basis of Agamben’s analysis, I develop the concept of the ‘generalised biopolitical border’ which, as a critique of the modern geopolitical imaginary, can be read as a response to those who call for a more pluralised and radicalised view of what and where borders are in contemporary political life. Finally, in addition to drawing upon the insights of poststructuralist thought to problematise the concept of the border of the state and develop alternative border imaginaries, the book also uses the problem of borders to explore some of the limitations of the poststructuralist work under consideration. While the concept of the generalised biopolitical border is shown to be one suggestive response 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:07 Page 10 10 BORDER POLITICS to the need for different thinking about borders, problems with this approach are identified in the light of aspects of the work of Derrida. In this way, as well as a contribution to thinking differently about borders in political life, the book can be considered as a critical introduction to and commentary on some of the key thinkers associated with a post-structualist perspective. MAP OF THE BOOK The book is organised into five chapters. The first chapter seeks to illustrate Étienne Balibar’s point that borders are vacillating and not necessarily where they are supposed to be in contemporary political life. To do this I look at three examples of bordering practices that challenge the modern geopolitical imaginary underpinned by the concept of the border of the state: the emergence and implementation of the United Kingdom’s new global border security doctrine; the recent activities of Frontex, the new European Union (EU) border management agency, in Africa; and the indefinite detention of suspected terrorists at the United States Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. These illustrations provide a crucial empirical backdrop that demonstrates the overall importance of developing new ways of identifying and interrogating borders in the light of contemporary practices. Chapter 2 then provides a tour d’horizon of the study of borders in IR, critical geopolitics, and the interdisciplinary subfield of border studies. The aim is to offer an impression of the current ‘state of the art’ of existing literature that deals in various ways with the concept of the border of the state. To this end, the primary purpose of the survey is to accumulate, in a positive fashion, different insights and perspectives from a range of writings that can be mobilised to assist in conceptualising emerging practices of the kind outlined in Chapter 1. I argue that it is possible to detect the beginnings of a shift in border studies from a geopolitical to a biopolitical horizon of analysis but that, while this has opened up new and exciting avenues of enquiry, these have yet to be fully exploited for: 1. interrogating the concept of the border of the state; and 2. developing different ways of conceptualising what and where borders are. As such, there is still much work to be done. On this basis, I situate the book as a contribution to 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics Introduction 29/11/11 16:07 Page 11 11 ongoing interdisciplinary efforts to employ a biopolitical approach to the study of borders. Chapter 3 moves away from the IR and related literature to explore potential resources in post-structuralist thought for an interrogation of the concept of the border of the state. Developing some of the insights of the literature outlined in the previous chapter, I seek to highlight and examine the relation between state borders and practices of violence, sovereignty, and (bio)power. First, the work of Benjamin and Derrida is drawn upon to analyse the violent foundations of the juridical–political order and the work that borders do in upholding such violence. Second, I use Schmitt’s paradigmatic account of sovereignty and later treatment of the relationship between spatial ordering and law to offer an interpretation of borders as exceptional spaces. Third, Foucault’s treatment of (bio)power and notion of biopolitics are explored more fully, which offers further scope for a critical interrogation of the concept of the border of the state away from the confines of the modern geopolitical imaginary. Chapter 4 traces Agamben’s engagement with and development of Foucault’s understanding of the biopolitical structures of the West in order to explore the possibilities of his approach for developing alternative border imaginaries. It begins with an exegesis of Agamben’s work although departures are made from extant interpretations in respect of his concept of bare life, the importance of what he calls a ‘logic of the field’, and the spatial dimensions of his thought more generally. Building upon Agamben, I develop the concept of the generalised biopolitical border as an alternative to the geopolitical concept of the border of the state. Thinking in terms of the generalised biopolitical border unties an analysis of the limits of sovereign power from the territorial confines of the modern state and relocates such an analysis in the context of a global terrain that spans and decentres notions of ‘domestic’ and ‘international’ space. Chapter 5 begins by assessing what the implications of the concept of the generalised biopolitical border might be and how this differs from the concept of the border of the state. It does so by returning to the examples of the work that the latter does in contemporary political life in respect of framing our understanding of juridical–political order, the production of identities of citizen-subjects, and global security relations. By rereading these examples in the light of the concept of the generalised biopolitical border, I then explore how this alternative 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics 29/11/11 16:07 12 Page 12 BORDER POLITICS frame might entail new modes of practice/theory. Drawing on Derrida’s account of the politics of framing, however, I end on a note of caution about the way in which thinking in terms of the concept of the generalised biopolitical border runs the risk of foisting the same problematic sense of form, shape, and coherence on ‘global politics’ as a totality in the same way that the concept of the border of the state has done. NOTES 1. See Anderson, Frontiers, 1996; and Prescott, Political Frontiers and Boundaries, 1987. 2. Agnew, ‘The Territorial Trap’, 1994. See also Jackson, The Global Covenant, 2000; and Williams, The Ethics of Territorial Borders, 2006. 3. See Agnew, ‘The Territorial Trap’, 1994; Ruggie, Constructing the World Polity, 1998; Ó Tuathail and Dalby, Rethinking Geopolitics, 1998; Teschke, The Myth of 1648, 2003; and Walker, Inside/outside, 1993. 4. In this sense it is what William Connolly refers to as ‘onto-political’; Connolly, ‘The Irony of Interpretation’, 1992. See also Connolly, The Terms of Political Discourse, 1993. 5. Bartelson, The Critique of the State, 2001; Walker, Inside/outside, 1993. 6. Camilleri et al., The State in Transition, 1995, pp. 1–4. 7. Weber, ‘Politics as a Vocation’, 1948, p. 78. 8. See Elden, ‘Contingent Sovereignty’, 2006 and ‘Blair, Neo-Conservatism and the War on Territorial Integrity’, 2007. 9. See Butler, Precarious Life, 2004, p. 32. 10. Linklater and MacMillan, Boundaries in Question, 1995, p. 12 11. Borger, ‘Security Fences or Barriers to Peace?’, 2007, p. 23. 12. Brown, ‘Borders and Identity’, 2001, p. 117. 13. Jackson, The Global Covenant, 2000, p. 316. 14. Albert, ‘On Boundaries’, 1999, p. 54. 15. Lapid, ‘Introduction: Nudging IR Theory in a New Direction’, 2001, pp. 6–7. 16. Linklater and MacMillan, Boundaries in Question, 1995. 17. Walker, ‘Editorial Note’, 2000, p. 2. 18. Williams, ‘Territorial borders’, 2003, pp. 25–46. 19. Donnan and Wilson, Borders, 1999. 20. Rumford, ‘Introduction: Theorising Borders’, 2006. 21. Kolossov, ‘Border Studies’, 2005; Newman, ‘Boundaries, Borders and Barriers’, 2001; Paasi, ‘The Changing Discourses on Political Boundaries’, 2005. 22. Williams, ‘Territorial borders’, 2003, p. 27. 02 pages 001-190 text:Border Politics Introduction 29/11/11 16:07 Page 13 13 23. Brown, ‘Globalisation’, 2005, p. 167. 24. Strange, ‘The Westfailure System’, 1999. 25. Held and McGrew, The Global Transformations Reader, 2002, p. 39; Scholte, Globalisation, 2000, pp. 135–6. 26. Hirst and Thompson, Globalisation in Question, 1996 and ‘The Future of Globalisation’, 2002. 27. Carlson et al., ‘Foreword’, 2006, pp. 1–2. 28. Coward, ‘The Globalisation of Enclosure’, 2005, pp. 105–34; Newman, ‘Borders and Bordering’, 2006, p. 181. 29. Starr, ‘International Borders’, 2006, pp. 3–10. 30. Balibar, ‘The Borders of Europe’, 1998, p. 217. 31. Ibid., p. 220. 32. Ibid., pp. 217–18. 33. Walker frequently implies the inadequacy of the inside/outside model conditioned by the concept of the border of the state. See: Walker, Inside/outside, 1993, pp. 20, 159, 161; ‘Sovereignty, Identity, Community’, 1990, p. 180; ‘Foreword’, 1999, p. xii; ‘On the Immanence/Imminence of Empire’, 2002, p. 343. 34. Walker, ‘International/inequality’, 2002, p. 17. 35. Mbembe, ‘Necropolitics’, 2005, pp. 11–40. 36. Weizman, ‘On Extraterritoriality’, 2007, p. 13. 37. Bigo, ‘The Möbius Ribbon’, 2001. 38. Campbell, Writing Security, 1998; National Deconstruction, 1998; Moral Spaces, 1999. 39. Z. Laïdi, A World Without Meaning, 1998, p. 97. 40. Lapid, ‘Introduction’, 2001, p. 2. 41. Parker, ‘A Theoretical Introduction’, 2008. 42. Rumford, ‘Introduction’, 2006. 43. Ó Tuathail and Dalby, Rethinking Geopolitics, 1996, p. 29. 44. Shapiro, Challenging Boundaries, 1996; Violent Cartographies, 1997; Moral Spaces, 1999. 45. Walters, ‘Mapping Schengenland’, 2002; ‘Border/Control’, 2006. 46. Walker, Inside/outside, 1993, p. 159. 47. Jacques Derrida, for example, is ‘eager to maintain [the concept of poststructuralism] as suspect and problematic’, see: Derrida, ‘Deconstruction: the Im-Possible’, 2001, p. 16. 48. As Noel Parker puts it: ‘post-structuralism leaves in question the solidity of entities themselves’, see Parker, ‘A Theoretical Introduction’, 2008, p. 11. 49. Foucault, ‘Problematization’, 1991. 50. Foucault, Madness and Civilisation, 2001 [1959]. We hope you have enjoyed this short preview. Border politics: The limits of sovereign power by Nick Vaughan-Williams can be purchased from Amazon here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Border-Politics-Limits-Sovereign-Power/dp/074863732X Other reputable book sellers are also available.